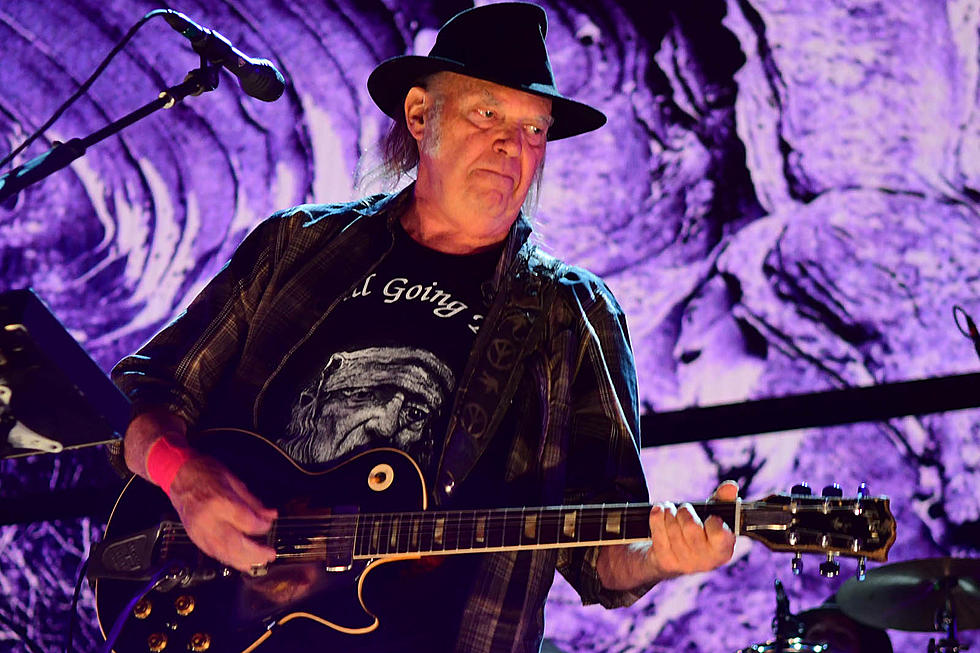

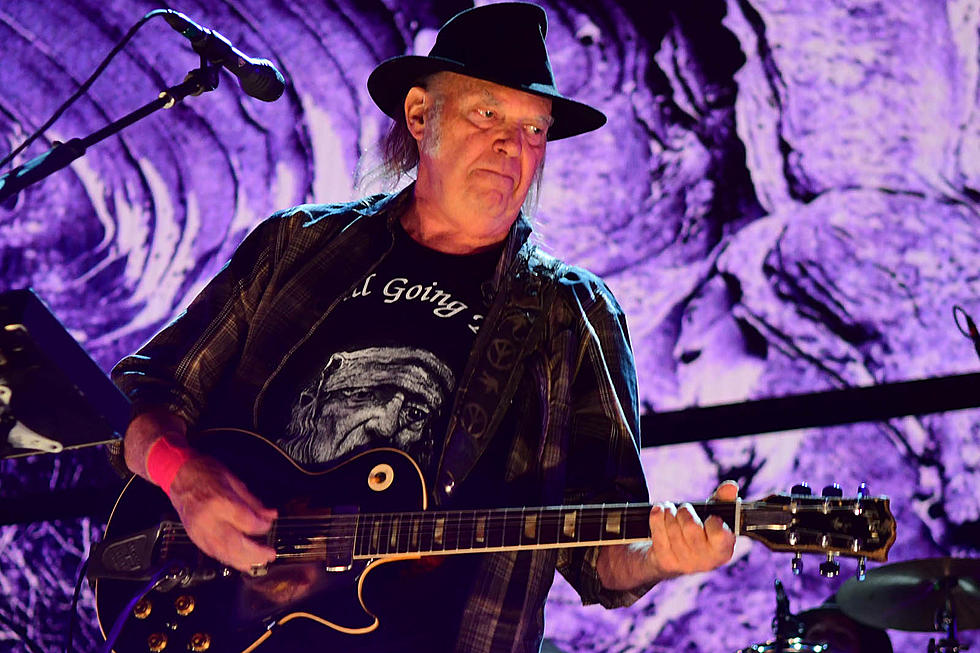

When Neil Young Began the Turbulent ’80s With ‘Hawks & Doves’

By the end of the '70s, Neil Young's fans had been trained to expect constant change, but his creative shifts from album to album could still be painfully jarring. Hawks & Doves is a prime example.

Released Oct. 29, 1980, Hawks & Doves arrived at a particularly critical moment in Young's career. After making it through a tumultuous decade of wild creative and personal highs and lows, he closed out the '70s on a rapturous high note with the double-barreled shot of 1979's Rust Never Sleeps and Live Rust LPs. Triumphantly restless, humming with a feral energy that managed to move Young's music forward without severing its essential thread, the Rust records suggested he was shifting into a higher gear as a songwriter and recording artist.

Unfair as those expectations might have been, they were soundly dashed by Hawks & Doves, which somewhat awkwardly bolted together sessions from different periods. Side one, dubbed "Doves," rescued a handful of tracks from Young's aborted 1975 Homegrown LP, while the "Hawks" side consisted of more recent songs, recorded earlier in the year, with a pronounced country bent. The entire nine-track collection clocked in a few seconds shy of half an hour in length.

Questions of heft aside, the album — particularly the "Hawks" tracks — presented a side of Young that made many longtime fans uncomfortable. Long seen as a standard bearer for the counterculture movement, Young seemed to pull an about face with songs like "Union Man," which took a biting swipe at the musicians' union, and the title track, which included cries of "U.S.A.! U.S.A.!" and the lines "Got rock and roll, got country music playing' / If you hate us, you just don't know what you're sayin'." Coming from one of the men responsible for the protest anthem "Ohio" — and on the eve of Ronald Reagan's election as President of the United States — it stung some listeners as a betrayal of '60s ideals.

Ideology aside, it was hard to shake the feeling that Hawks & Doves lacked the drive and focus that had so recently enlivened Young's music. It was easy to assume the record was just one more in a series of occasionally inscrutable moves, even though it would actually end up being one of the more accessible albums Young released during a very challenging decade. But what fans, and even most of the executives at Young's label, didn't realize was that he'd recently begun to deal with some personal challenges that made music far less of a priority.

Listen to Neil Young Perform 'Union Man'

Ben Young, born to Neil and his wife Pegi on Nov. 28, 1978, was diagnosed with cerebral palsy not long after his birth — and while Young had experience with the illness, given that his older son Zeke had received the same diagnosis, Ben's was far more complicated and severe, leaving him confined to a wheelchair and unable to speak. Determined to help their son however they could, the Youngs entered an intensive "patterning" program designed to, as Neil put it in Jimmy McDonough's Young biography, Shakey, "save your kid."

The program, described by Young as a "rigorous" series of exercises that took up "13, 14 hours a day, seven days a week," couldn't help but take a toll on his emotional well-being — and leave his once all-consuming creative drive simmering on the back burner.

"These people have told us that if he didn't make it, it was gonna be our fault. That we didn't do the program right," Young told McDonough. "They have you so scared that if they call and you're not at the house, you're off the program. Forget it, you've ruined it for your kid. And here we are, we think this is the only thing we can do — they've drilled that into us — and if you don't do it exactly the way they say, bango! You're out."

This grueling period was only just beginning when Young released Hawks & Doves, and would arguably have a far more profound effect on his next LP, 1981's even more confounding Re-ac-tor. The aftermath of the family's time in the program, during which Young set out to devise his own method of communicating with Ben, directly fed into 1982's divisive Trans.

Riding a string of gold and platinum albums into the '80s, Young saw his sales start to tumble with the Hawks record — not that he was willing to do much about it.

Listen to Neil Young Perform 'Little Wing'

Never one to willingly play the promotional game or spend much time discussing his process even under the best of circumstances, Young insisted on taking a step back from the spotlight during this period. He stayed off the road for four years and opted to keep his family's trials completely private, much to the chagrin of manager Elliot Roberts. "I wasn't allowed to tell people that Neil was involved in therapy with Ben 18 hours a day, and that's why he could not promote anything," Roberts is quoted as saying in Shakey. "I could never use that as an excuse, because it would become the story. One thing we didn't want was pity."

True to Young's wishes, pity was in short supply during Young's experimental '80s phase, and although he's always stood behind much of his work from the era — and each of those albums have steadily acquired their own level of cult appreciation over the years — he looked back on it later as a time of emotional distress so profound he couldn't even comprehend it as it was happening.

"I closed myself down so much that I was making it, doing great with surviving – but my soul was completely encased," Young admitted in 1990. "I didn’t even consider that I would need a soul to play my music, that when I shut the door on ‘pain,’ I shut the door on my music. That’s what I did. And that’s how people get old."

Neither as challenging as Young's most idiosyncratic work nor as memorable as his most substantial efforts, Hawks & Doves, in retrospect, occupies a slightly uncomfortable middle ground in the catalog of an artist who's always sounded his best when hammering at the margins, and its shortcomings highlight issues that would continue to nag at his music for much of the decade.

"That whole era, there's always something wrong," Young remarked of the '80s during a 1992 interview with the New York Times. "There's always something between me and what I'm trying to say. The invisible shield."

Ranking Every Neil Young Album

More From Ultimate Classic Rock