50 Years Ago: The J. Geils Band Emerge on Their Debut

After spending years honing their rafters-rattling live act — and making multiple attempts at distilling all that on-stage energy in the studio — the J. Geils Band released their first album on Nov. 16, 1970.

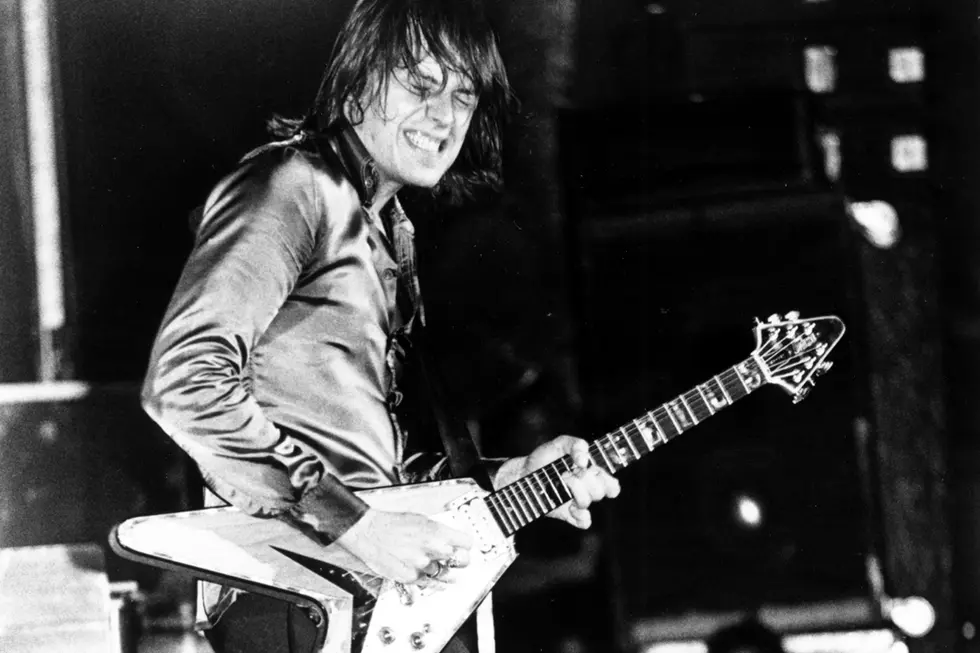

Although the band was an unknown quantity to many record buyers (and would sadly remain so for quite a few years), they were local legends on the Boston live circuit, where they'd earned a reputation for sweaty, blues-soaked sets driven by John Geils' stinging guitar, molten harmonica from Richard "Magic Dick" Salwitz, and the manic energy of frontman Peter Wolf.

Long before Boston and Aerosmith put the city on the multi-platinum map, the J. Geils Band's blend of judiciously chosen covers and road-tested originals made them Boston's preeminent musical ambassadors.

It wasn't a sound that developed overnight. When they started out in the mid-'60s, Geils, Salwitz, and bassist Danny "Dr. Funk" Klein performed as an acoustic blues trio they dubbed Snoopy and the Sopwith Camels, with Klein playing a washtub bass. Wolf and drummer Stephen Jo Bladd, meanwhile, were part of a competing act called the Hallucinations — and in 1967, with the Hallucinations split up and the Camels ready for a change, they joined forces to form the J. Geils Blues Band.

The arrangement started as a casual marriage of convenience, but the new bandmates soon realized that the revamped lineup produced just the sound they'd been looking for — and made them a much more popular draw at local clubs, where they went from playing for peanuts to commanding top-dollar rates from promoters. By 1968, they'd attracted the attention of record exec Mario Medious, a promo man for Atlantic Records whose growing legend (and flashy personality) would later earn him the nickname "the Big M."

For Wolf, who'd fallen deeply in love with the deep catalog of classic soul records released through Atlantic in the '40s, '50s, and beyond, the chance to record for the label was too tantalizing to resist. While they weren't overly eager to make the jump from the stage to the studio, Atlantic seemed like the best potential home for the group — provided, as Wolf insisted during contract negotiations, that the J. Geils Band only issued its recordings through the label proper instead of any of its subsidiary imprints. For Atlantic VP Jerry Wexler, who'd personally helped oversee many of Wolf's favorite records, it was a demand the label was only too happy to concede.

"We were tickled pink, man," Wolf told the NME in 1973. "We thought we'd end up on Din-Dang records or something like that. First time we met all those guys from Atlantic, we'd just ask 'em about Wilson Pickett and Don Covay. Atlantic was like some dream, because of that catalog they had."

Atlantic's storied past made it the perfect home for the band, but it still wasn't an immediate match made in heaven. Like a good number of groups known for their live act, they struggled to transfer that energy into the studio, and their first sessions for the label were less than productive. As 1968 rolled into 1969, the J. Geils Band had an aborted attempt at an LP in the vaults and a growing sense of frustration among members of the group who wondered why a sound that possessed such incendiary fury in concert should lose so much of its power on tape.

It's a question that's dogged countless acts, and one that would continue to haunt the J. Geils Band throughout their recording career — but on the road to their first studio effort, the final missing ingredient turned out to be keyboard player Seth Justman, a fan of the group who made his way into the lineup and quickly proved a strong creative foil for Wolf. When they returned to the studio with producers Dave Crawford and Brad Shapiro to record what became The J. Geils Band, the band's selection of originals included a number of new songs written by the duo.

In fact, of the five originals scattered throughout the self-titled effort, three were Justman/Wolf co-writes — a precedent that would evolve into a pattern over the next decade, as the J. Geils Band grew to rely less on covers of blues, soul and R&B classics while continuing to refine and evolve its sound. To their immense credit, the self-penned material recorded for The J. Geils Band holds up well next to cuts from some legendary acts — including John Lee Hooker ("Serves You Right to Suffer"), Smokey Robinson ("First I Look at the Purse"), Otis Rush ("Homework"), and Albert Collins ("Sno-Cone").

The record was greeted with praise from the press, but failed to turn the band into an immediate sales sensation, peaking at a less-than-impressive No. 195 and kicking off a period in which a grueling run of tour dates didn't seem to make much of an impact on their wilting commercial fortunes. The era was aptly summarized by the rumpled hotel room depicted on the cover of their next record, 1971's The Morning After.

It was with Morning that all those stages finally started paying dividends in record stores and on the radio, with a Top 40 cover of the Valentinos' "Looking for a Love." With the 1972 live release Full House and the following year's Bloodshot, the J. Geils Band earned their first two gold albums — and although they'd remain something of a mid-level act until they hit the Top 20 with Love Stinks in 1980, the '70s found the group churning out a series of increasingly confident efforts that distilled their love for those classic soul records while adding a modern rock spin.

All along, as Wolf argued to Disc, the band's music was simply a heartfelt act of homage to the artists that had always inspired them — and whose recordings had been short-sightedly consigned to the "race records" charts before Wexler and Atlantic helped bring them into the pop mainstream. "The best music made comes from black America, man," Wolf said. "People say, 'Why are you white people playing black music?' We say, 'We play music that behooves us and moves us.'"

See the J. Geils Band Among the Top 100 Live Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock