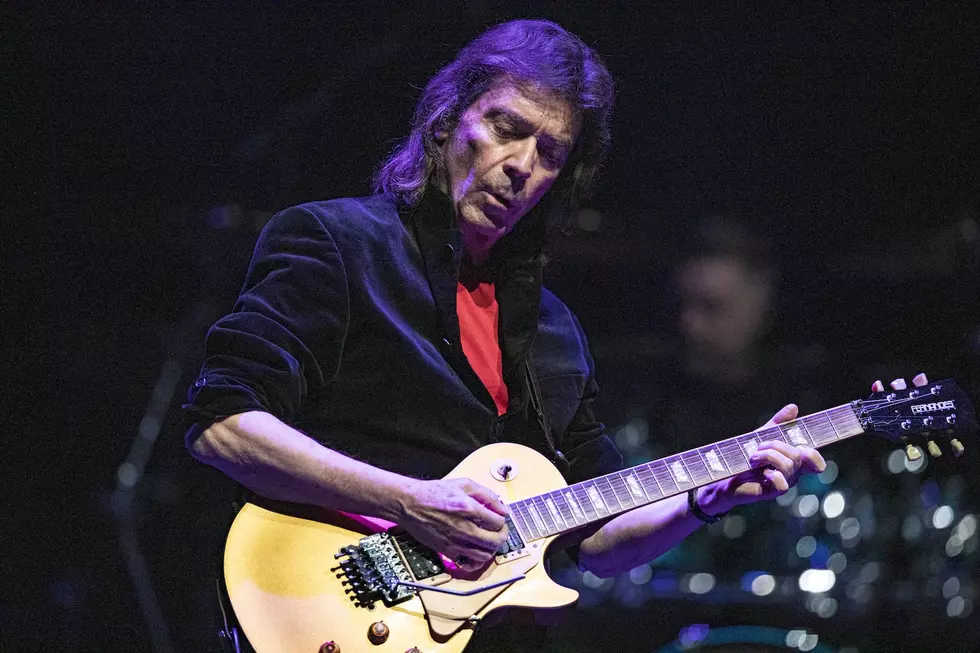

When Steve Hackett and Steve Howe Briefly United for ‘GTR’

If you were to tell music fans in the ‘70s that Steve Howe and Steve Hackett would one day form a band, chances are their expectations would be far different from what ultimately arrived with the self-titled debut by GTR.

The birth of the band came at a time when Hackett and Howe, who had just left Asia, were keen to experiment and try something new.

“I think at the time, you could either make the kind of album that was designed for other musicians to like or you could try and widen it and gain a whole new audience," Hackett tells UCR. "We were both in our mid-30s at that time, so I think there was the feeling, ‘Are we still young enough to be pop stars here? Or really should we be emphasizing the jazz odyssey aspect?’

"We were interested in lots of different kinds of music – everything from flamenco to country music – but I think we were trying to make an accessible, rather than impenetrable album," Hackett added, "and indeed, it gained a lot of young teenage listeners, right across the board. So we were very lucky to pick that up, considering that we had both come out of very male-orientated listening camps. The people that were into Genesis, at least during the time when I was part of the band in the ‘70s, were mainly male, and I think the same thing [was true] for Yes. It proved that it was possible to cross over and change people’s ideas of what the guitar could do.”

A lot of time was spent working out the concept of what GTR would be prior to the LP's arrival in July 1986. Hackett says they spent about two years “running about” and working on the idea, followed by nine months recording the album. The bulk of the period leading up to entering the studio was spent writing songs and solidifying the group’s lineup, which led to some discussions and division with their prospective label.

“It looked like we were going to sign to Geffen, but Geffen’s label really wanted everyone in the band to be a star,” Hackett recalls. “In other words, they wanted an Asia Mach II, and we had two guys who were well known. I think we decided to make the emphasis the guitar connection, otherwise we might have been called Anderson, Bruford, Wakeman, Howe and Hackett. I think that there’s always a danger with something like this – that you can get caught in the crossfire of a reformation of Yes or Asia or any other British band for that matter.”

In the end, the idea of signing with Geffen fell apart completely, and Hackett believes it was for the best.

“After we’d spent a tremendous amount of time and money on amassing the songs, I think we failed the audition with Geffen,” he says. “They didn’t like the songs, and they didn’t like the personnel, whereas Clive Davis did. Clive got involved, and he did a tremendous job on it. At the same time, I think we realized that we were making something that was designed to be a Top 10 record.”

Signing a deal with Davis and Arista, Hackett and Howe were finally free to move forward with a lineup that was closer to their vision for the group. GTR was completed with bassist Phil Spalding, drummer Jonathan Mover and vocalist Max Bacon, with whom Hackett had some prior history.

“He was from a band called Nightwing, and I’d worked with them on a couple of songs a year or so earlier, and I thought he was especially good as a ballad singer," Hackett says, "but what I didn’t realize was that he was a great rock singer too. He really had a very powerful voice that was very reliable night after night."

Hackett and Howe were well aware of what that they were up against. At the same time, having two well-known guitar players with strong opinions working on one project might seem complicated, but Hackett says there was a specific vision in play. “I felt that the two of us would bring out brilliant spirits to bear on this," Hackett says.

"What we were aware of was the idea that we had to make it as songwriters on this," he added. "'When the Heart Rules the Mind' was the track that was the hit, which Steve Howe and I had written. Geoff Downes had written ‘The Hunter,’ the second track which was the second single, which didn’t fare as well. But I had the impression that Geoff was considered by Clive Davis to be the writer and that we were really the musicians – and in fact, of course, in the long term, what proved to be correct was that it was the track that Steve Howe and I wrote together that was the hit. There really wasn’t a second single from that album. I think that if there had been, we would have been giving Fleetwood Mac a run for their money.”

Listen to GTR Perform 'When the Heart Rules the Mind'

The album would ultimately employ a lot of the technology from the day, so Downes was an important presence as the producer – especially when it came to helping Howe and Hackett navigate these new technological waters.

"I think he was very honest with us," Hackett notes. "We were using guitar synths and so he said, ‘Well, that’s all very well, but what you’re using is just cheap monophonic synths. You’re using last year’s synths – this is what keyboard players could do last year. Today, we’re using Synclavier.' At the time, he owned a Synclavier that was probably more valuable than his house, such was the price of reliable samplers at that time. So we started working with the Synclavier using MIDI control with the guitars.

"Now, of course, the technology at the time afforded the possibility of that, but it wasn’t by any means reliable," Hackett adds. "You had MIDI delay, you had various things that [presented challenges]. Whatever we recorded, we were having to do offsets to pull the thing back into time. So yes, it could be done with guitar but it was slower doing it with guitar – and there were some extraordinary noises that came out.”

Howe expanded on what Downes brought to the table as a producer in the liner notes from the album's 2015 reissue: “We wanted this to sound like an arena rock band, but to also retain the intricacy and complexity of the music. Geoff was really good to work with on this. We talked the same language and a lot of things just happened spontaneously in the studio.”

The veteran guitarist had worked extensively with Downes in both Yes and Asia, and describes him as someone who was “very hard working and methodical. [Downes] always encouraged us to come with ideas in the studio, but I knew when to get out of his way and let him get on with the job.”

Still, Howe admits, “obviously, I would have been happy if there had been more virtuoso playing included on the album, and I did record extra parts that were never used. But I can appreciate that if we had filled the album with a lot of virtuoso stuff then the canvas would have been more crowded and this could have distracted from the impact. It was the difference between the '70s mentality, when musicianship came first, and the '80s, which had a more stripped-down attitude.”

Hackett admits that Howe “had to fight our corner very hard,” adding that “sometimes we fought against each other in order to get the thing absolutely right. I think we wanted to make the kind of album that competed in the marketplace rather than competing with each other, trying to knock each other off our respective perches with regards to speed and all of that. So we didn’t make the kind of album that was reduced to the level of sport. Nobody’s trying to sprint faster than anyone else on it. We made the kind of album where I think we tried to do the right thing for the song.”

As he points out, “keyboard was reigning supreme at the time” and in Hackett's view “we were part of the guitar fight back. I think we started something – we showed that guitars were viable again.

"It was very pleasurable, but it was a lot of hard work," Hackett adds. "I had to stay very focused and I had to hang onto my helmet quite a lot during that process and just accept the fact that I couldn’t have my own way with everything. But if Steve Howe got his way 40 percent of the time, and I got my way 40 percent of the time, then the other 20 percent we could afford to have some latitude."

At the same time, Hackett says "the record company certainly were concerned with the mixes and the way it sounded, so we weren’t giving as much artistic freedom as perhaps we wanted. In fact, I think the first mix of 'When the Heart Rules the Mind' was rejected. Instead, they went with a second mix "which I think was less good, in fact, but it sounded great on American FM – compressed [mixes] on American radio sounded wonderful."

Howe has high praise for “When the Heart Rules the Mind,” calling it a “classic” song. “It might not be right for me to say so, but it is," Howe added. "It was such a powerful anthem. It was a pop hit, but not ‘pop’ in the bubblegum sense. It was the sort of big track that pulls everyone together.”

Hackett said “part of the appeal of ‘When the Heart Rules the Mind’ was the fact that it was also harmony-based on the chorus. In fact, some of the early mixes of that sounded a little bit like the Beach Boys, but the harmonies were thinned out. There were some extraordinary renditions of that before it became the final mix.

"It wasn’t without its critics of course, at the time, who accused us of selling out and all of the rest," Hackett adds. "But at the end of the day, if you have success, it’s in the nature of success to have its critics. But I think that we knew what we were doing: We wanted to have a hit record. We didn’t just want to make something that was an esoteric masterpiece.”

Listen to GTR Perform 'The Hunter'

One of the most famous critical responses came courtesy of J.D. Considine, who used just three letters, “SHT,” when reviewing the album for Musician in 1986.

"I think that people tend to remember negative criticisms," Hackett says now, adding that he doesn’t recall seeing Considine’s review. "When you’re in the thick of it, you have to be very focused if you want to have a hit. I think at that point in time, I’d proved whatever I felt I had to prove with Genesis. And then I thought, ‘If I could prove it with GTR again, then people would think, ‘Well, it’s not just a coincidence.’

"I think there were more compromises to be made at that time, but I think that at the time, I did all sorts of things. I did all sorts of stuff to make the package work. We had to do a glossy video and several of us dieted to the point where we dropped [a lot of weight]," Hackett adds. "I think you have to be very fit to be successful. I think maybe today’s equivalent would be the boy bands and all of the compromises that they make in order to make something happen.

"Of course, you know, we had the pedigree of whatever we’d done before – so for me, it was an exercise that I realized it was a temporary exercise and not selling out as such, but pawning your heart and I retrieved it after that," Hackett argues. "But I was very proud of what we did. It’s a little bit the same, if you asked John Lennon about this, [whether] he thinks that the Beatles sold out, he would be the first to say it – but hey, you know, we were all very happy with that.

"You know, when you’re listening with the ears of a 12-year-old to what the Beatles had achieved, I certainly wasn’t prepared to condemn anybody because they weren’t doing symphonies at the time," Hackett concludes.

GTR's failure to produce a strong second single kept the band from really taking off, he adds, shortening their lifespan. But that was just as well for Hackett, who quickly exited.

“It was never going to be a long-term project for me," he says. "I realized that it had novelty value. People were going to go out and buy the first album because they wanted to hear what the combination of Genesis and Yes and Asia might sound like. So it was a coming together of separate careers and backgrounds. You know, beyond that, I thought, ‘Everyone’s going to be interested in the first record, but I don’t think anyone’s going to be interested in the second record.’ We had one successful single and the second single flopped and the writing was on the wall.”

Howe has a different opinion on what eventually brought the group to an end. “Steve and I came from a different perspective," he noted. "He had been used to being out on his own and putting together a band, whereas I had always been in a long-term band. I was more of a team player, perhaps. But he was becoming increasingly distant from the rest of us and a little resentful. However, I don’t blame him for what happened. If anything, I was more to blame. Maybe I should have done more to accommodate Steve.”

Efforts to move forward in the wake of Hackett’s departure found Howe working briefly with both Robert Berry on guitar and, eventually, Saxon’s Nigel Glockler on drums, but things didn’t get very far. They worked on some demos, but Berry’s exit to work with Keith Emerson and Carl Palmer in the band 3 put an end to the idea of keeping GTR together. "I thought it was a shame," Howe said, "because to me, GTR could have been self-perpetuating."

Nevertheless, both Hackett and Howe retain a lot of affection for what they created with the GTR album. “It was one of the most extravagant albums I ever made,” Howe says. “We were a band who took our music very seriously, as we should have done. Because of this, we reached a consistently high standard. I can stand up and say, ‘This is the GTR album. It’s part of my career and I’m delighted to have done it.’ But once Steve and I took this into the big wide world, we were clinging to the rocks, as it were. We weren’t prepared for what its success would do to us.”

Genesis Solo Albums Ranked

Steve Hackett Released One of Rock’s Most Hated Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock