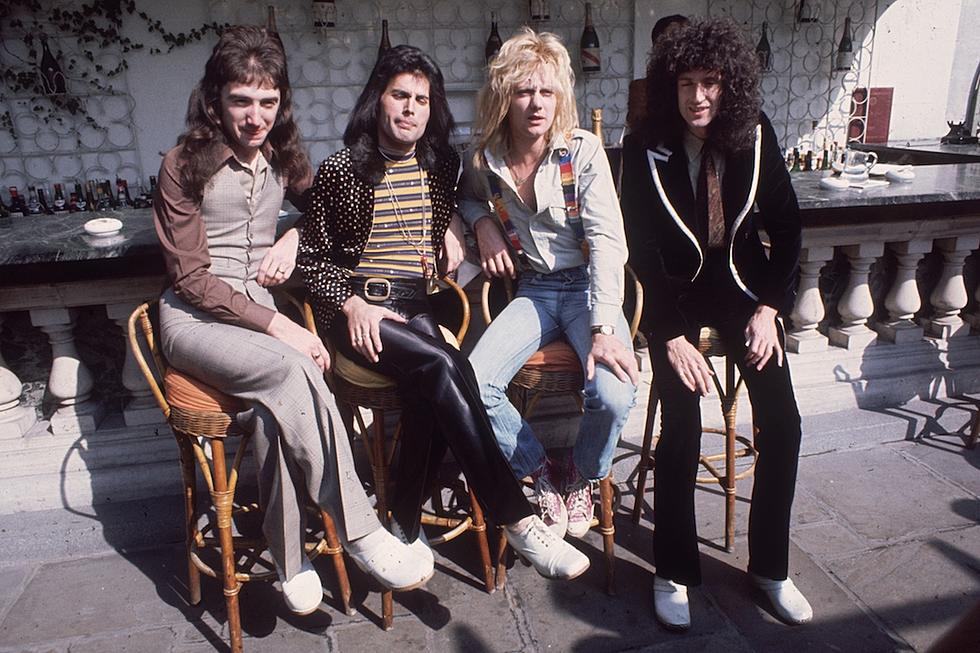

Freddie Mercury’s Sexuality Remained a Mystery Even to His Queen Bandmates

They didn't know. Maybe, they didn't want to know.

Queen never talked much about Freddie Mercury's sexuality, and even less about the disease that eventually killed him. "We were very close as a group," drummer Roger Taylor said, not long after Mercury died of AIDS in 1991. "But even we didn't know a lot of things about Freddie."

Still, Mercury's bandmates were confident of one thing: He couldn't be defined in some superficial, binary way. That simply doesn't reflect the complexity that shot through every element of Mercury's life and, of course, the band he once fronted.

If anything, some say, Freddie Mercury was bisexual, long before that became such a commonly discussed thing. "I don't think even he was fully cognizant in the beginning," guitarist Brian May once told the Daily Express. "You're talking to someone who shared rooms with Fred on the first couple of tours, so I knew him pretty well. I knew a lot of his girlfriends, and he certainly didn't have boyfriends in those days, that's for sure. I think there was a slight suspicion but it never occurred to me that he was gay."

Mercury kept to himself, perhaps as a defense mechanism but also because he liked to cultivate a sense of mystery. It worked: Questions about just how Mercury might be portrayed dogged the Queen docu-drama Bohemian Rhapsody, even before it was released to theaters. May added that Mercury revealed to Queen that he also liked men only "years after it was obvious."

"The visitors to Freddie's dressing room started to change from hot chicks to hot men," May told the Times of London in 2017. "It didn't matter to us; why should it? But Freddie had this habit of saying, 'Well, I suppose you realize this, that or the other,' in this very offhand way – and he did say at some point, 'I suppose you realize I've changed in my private life?'"

Some argue this shift was only a belated manifestation of feelings that were always there, rather than any kind of sudden realization. Classmates at the St. Peter's Church of England School in Panchgani, India, an elite boarding school where the young Tanzania-born Farrokh Bulsara had begun school at age eight, apparently always suspected he might be gay. Needless to say, times were different in 1954.

"He had this habit of calling one 'darling,' which I must say seemed a little fey. It simply wasn't something boys did in those days," schoolmistress Janet Smith says in Mercury: An Intimate Biography of Freddie Mercury. "It was accepted that Freddie was homosexual when he was here. Normally, it would have been, 'Oh, God, you know, it's just ghastly.' But with Freddie somehow it wasn't. It was okay."

The Bulsaras eventually ended up in Middlesex, near London, after the family's homeland – then called Zanzibar – was consumed in a revolution in 1964. There, Farrokh Bulsara was permanently left behind for Freddie Mercury, though every contradiction was in place from the start.

Watch Queen's 'Bohemian Rhapsody' Video

His outfits were wildly androgynous; his onstage persona incorporated a theatrical sense of camp. "In those days, it was the fashion to be kind of dandyish, and I suppose we had a hand in creating the fashion," May told the Daily Express. "So there was this doubt in people's minds as to whether you might be gay or not. It was a convenient little place to be."

Even the decision to call his band Queen was meant to provoke, to color everything they did with a whisper of mystery: Is he or isn't he?

"The name was Freddie's idea," Taylor said in Is This the Real Life?: The Untold Story of Queen. At this point, the two were selling odds and ends at the famously bohemian Kensington Market, still hoping music could one day pay the bills. "In those days, there was a pretty eccentric crowd there, and a lot of them were gay and a lot of them pretended to be, and it just seemed to fit in," Taylor added. "I didn't like the name originally and neither did Brian, but we got used to it."

Tracks like "Bohemian Rhapsody," which so longed for an unreachable freedom, seemed to be hints as to what may have been deep inside his heart. "There's been so much analysis of the song, but I subscribe to the theory – and I never discussed it with [Freddie] – that it was his coming out song,” John Reid, Queen's manager at the time, said in Somebody to Love: The Life, Death, and Legacy of Freddie Mercury. May, on the other hand, vehemently disagreed.

Beyond the women Mercury dated during Queen's early years, he maintained a lengthy relationship with Mary Austin – first as a romantic partner and one-time fiancee, then as the closest of confidants. He revealed his sexual yearnings to Austin while Queen were at work on 1976's A Day at the Races – stating flatly back then that he was bisexual. "I told him, 'I think you're gay,'" Austin told the Daily Mirror in 2000. "And nothing else was said. We just hugged."

By the early '80s, Mercury's outlandish outfits had given way to a toned and trim style, perhaps as he grew more confident in his own skin. But trouble loomed, as the AIDS crisis swept through the gay community. After years spent unabashedly enjoying the sexually open disco scene in Munich, where Queen had recorded, Mercury submitted to a pair of AIDS tests. The results were negative in 1985, but he wasn't so lucky in 1987. Late in life, he'd settled into a sturdy partnership with Jim Hutton, but it was too late to save Mercury. A cocktail of drugs that soon made the illness manageable was not yet in common use.

Later, Somebody to Love sought to pinpoint the moment when Mercury contracted the human-immunodeficiency virus, saying he as already exhibiting some symptoms as early as September 1982 when Queen were in New York City for an appearance on Saturday Night Live.

Continuing a life-long trend, Mercury chose not to discuss any of this too deeply with Queen. "We knew something was going on," May admitted later on, "but it was not talked about."

Watch Queen's 'These Are the Days of Our Lives' Video

Eventually, Mercury was struck with AIDS, a group of debilitating symptoms caused by HIV. Finally ready to disclose his health issues, he returned to another familiar trope: "He said, 'I suppose you realize that I’m dealing with this illness,'" May told the Times of London. "Of course, we all knew, but we didn't want to. He said, 'You probably gather that I'm dealing with this thing and I don't want to talk about it, and I don’t want our lives to change, but that’s the situation.’ And then he would move on."

By the time Queen released The Miracle in May 1989, it had become clear to their singer that his time was running short. Mercury set about recording as much as he could, in the hopes of completing multiple Queen albums. He never told his parents he was gay or that he had AIDS.

"He decided to just invite us all over to the house for a meeting," Taylor told Rolling Stone in 2014. Mercury said, "You probably realize what my problem is. Well, that's it and I don't want it to make a difference. I don't want it to be known. I don't want to talk about it. I just want to get on and work until I fucking well drop. I'd like you to support me in this."

So much, as it always had, remained unspoken. The band closed ranks as work began on Innuendo, which followed in 1991. (Additional recordings from this period were later used to construct 1995's Made in Heaven.) May and Taylor, on more than one occasion, found themselves voicing their bandmate's unexpressed feelings.

"We didn't speak to each other about lyrics," May told Mojo in 2004. "We were just too embarrassed to talk about the words." May's "The Show Must Go On" and Taylor's "These Are the Days of Our Lives" "were things that we gave to Freddie as a way of him working through stuff with us." May told Rolling Stone. "And that wasn't spoken. It was us trying to find the end before we got there."

Despite his increasingly gaunt appearance, Mercury continued to deny reports that he had contracted AIDS – until he suddenly released a statement on Nov. 23, 1991. Mercury was found dead the very next day, as Taylor rushed to his bedside. Peter Freestone, Mercury's personal assistant over his last 12 years, called to say "don't bother coming."

Freddie Mercury remained a enigma: After all of this time, and after all of his many subsequent loves, Mercury's will dictated that Mary Austin – not Jim Hutton, or any other man before him – would receive nearly his entire estate. Austin, whom Mercury had described as the "love of my life," was also to spread his ashes in a secret location. She still lives in his elaborate mansion; the decor is unchanged.

"Anyone who portrays Fred as purely a gay story," May told the Daily Express, "is missing a lot of the point."

You Think You Know Queen?

Freddie Mercury: Year by Year Photos

More From Ultimate Classic Rock