45 Years Ago: First Glastonbury Festival Features David Bowie and Traffic

Free festivals were all the rage in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Bands would play for free. Fans would crash the gates for free. Free love. Free movement. Free drugs. And the organizers would end up in debt for a number of years afterward.

It was in this environment that Britain’s now-legendary Glastonbury Festival began on June 20, 1971. Thirty-something farmer Michael Eavis had seen Led Zeppelin headline a festival in Bath and decided to throw one of his own. He booked no less than the Kinks to play at his farm on Sept. 19, 1970. However, the Kinks didn’t show and T. Rex ended up headlining the first (and only) Pilton Pop, Blues & Folk Festival. Fifteen hundred people paid one British pound – which included free milk – to attend.

A few months later, Eavis wanted to create another festival with other like-minded folks, including Andrew Kerr, who had been inspired by 1970’s Isle of Wight Festival. Kerr aimed for a festival with noble ideals, reflecting the “Age of Aquarius.” Kerr and some of his associates could provide the money; Eavis could provide Worthy Farm. Even though it would take place at the farm in Pilton, Kerr decided to name the event after nearby (and more famous) Glastonbury. If Woodstock could take place in Bethel, N.Y., why not?

The Glastonbury Free Festival (also known as Glastonbury Fair or Fayre) was planned for June 20-24, 1971. This was a much grander event than the previous year’s Pilton fest. In terms of theming, it was all over the place, from plenty of Renaissance fair ephemera to elements of Brazil’s Carnival to hints of ancient Egypt. Creating what would become an iconic symbol of Glastonbury Festivals for decades to come, set designer Bill Harkin crafted a giant pyramid stage from scaffolding and sheet metal. According to Harkin, who got the idea from a dream, the stage was a one-tenth replica of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

So Glastonbury had money, land and a stage, but what about the bands? Organizers used connections to attempt to land a big act. The Grateful Dead and Pink Floyd were both interested at one point, but were forced to decline because of previous commitments or, reportedly, because the less-than-sturdy pyramid wouldn’t support the Floyd’s gear.

Still, the festival managed a respectable bill of around 20 acts, including Joan Baez, Traffic, Arthur Brown, Brinsley Schwarz, Hawkwind, Fairport Convention and pre-superstardom David Bowie. Some of these acts can be seen in the documentary co-directed by Nicolas Roeg (The Man Who Fell to Earth), although, sadly, not Bowie. David was set to headline Saturday night, but due to the organizers’ desire to avoid upsetting neighbors with late-night noise, he was pushed back to dawn on the next day. He took the stage with guitarist Mick Ronson and debuted a bunch of tracks from Hunky Dory, which he was recording at the time.

With 10,000 attendees, the modest festival was deemed a success – although, because of free admission, not a financial one. Roeg’s film (Glastonbury Fayre) brought some attention to the event and a triple-album (featuring many performances not from the fest) was released to recoup some of the costs. Regardless, another Glastonbury would not held until the late ’70s, and the festival did not become a regular event until the ’80s.

Throughout the years of Glastonbury, several things have remained constant: Eavis continues to be involved, some noble purposes are served in terms of charitable donations and the headliners still play on a big pyramid in the middle of a farm.

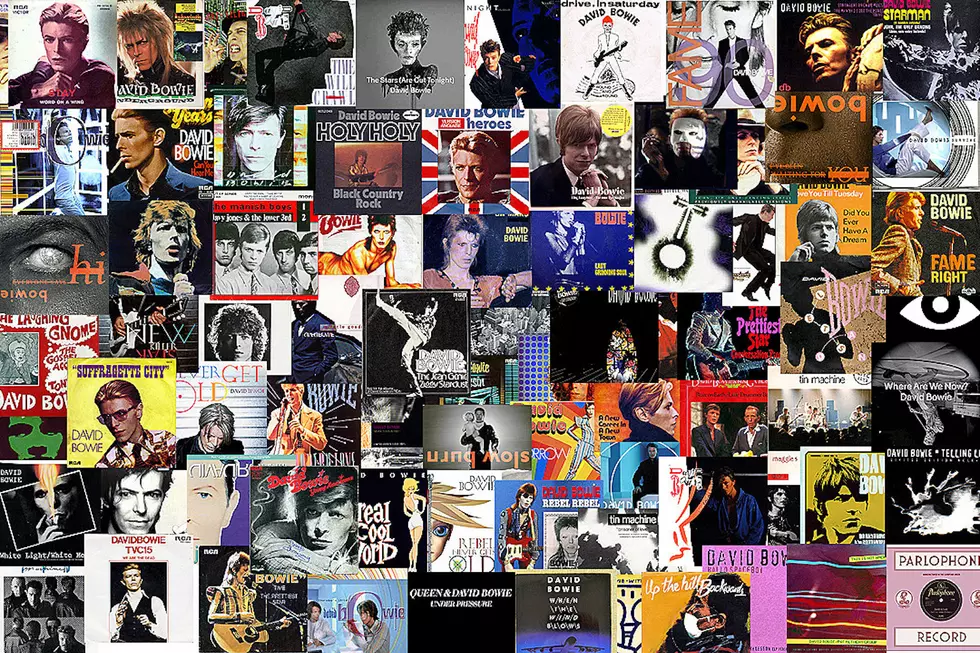

David Bowie Albums Ranked Worst to Best

More From Ultimate Classic Rock