David Crosby Sets the Record Straight: Exclusive Interview

Cameron Crowe is giving the elevator pitch for his documentary about rock legend David Crosby’s life, Remember My Name, which comes out on home video on Oct. 22. “They meet him, and he’s incredible, irascible,” he says. “Oh, my God, he’s dangerous and toxic! Oh, my God, he knows that! He’s surviving! Uh-oh, the roller coaster’s heading downwards. But now I feel for him, because I know him. Whew, he’s coming back up, and I’m rooting for him now. Oh, no, he’s scaring me a little bit. Wait … I love him!”

Crowe, who conducted the staggeringly candid interviews with Crosby – “The least known member of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young,” as Crowe jokes – that set Remember My Name, an epic documentary about Crosby’s tumultuous career, apart from the recent avalanche of rock 'n' roll documentaries, and who unusually lent his name to the project as executive producer, is blunt in his assessment that the film faces an uphill battle to get a fickle public’s attention.

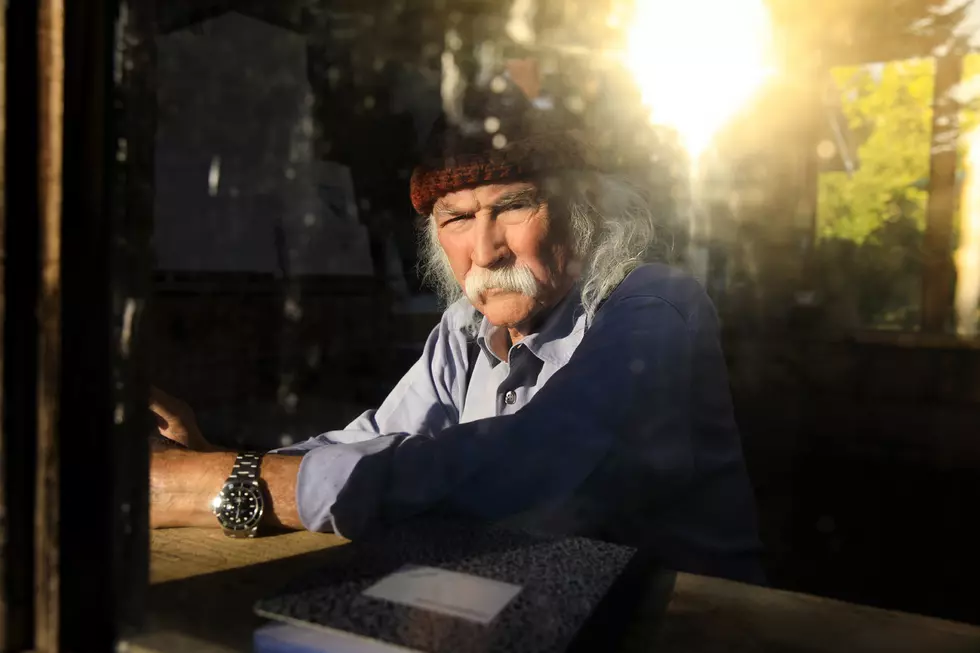

“I know, here’s this old guy in a hat. Why do I need to be interested in this guy?” Crowe asks with a chuckle. “But you can actually walk in not knowing David Crosby from John Mayer, because almost in the opening scene, there he is, at fucking 75, imitating John Coltrane’s horn, and it sounds like Coltrane! Everyone who’s seen the film, starts looking around at that point, like, ‘What the fuck? Who is this guy?’ So it’s more than just a rock doc. It’s a story about a guy who’s outlived all expectations, including his own. And the story we tell is, ultimately, What are you going to do with that? What are you going to do with your time? How do you spend that currency?”

Crosby -- one of the few performers still treading the boards who performed at 1969's Woodstock, which celebrated its 50th anniversary this summer -- began his career in the early '60s as a folkie. By no means the clean-cut heartthrob typical of the pre-Beatles period, but blessed with an angelic voice and a preternatural ability to choose just the right harmony part, he found stardom as one of the founders of Los Angeles folk-rockers the Byrds in the mid-60s. In their early prime, the band rivaled the Fab Four – whom they counted among their legion of fans – in both record sales, and breaking the mold with each new release through bold artistic endeavors.

But Crosby was fired from the Byrds in 1967. “He’d become intolerable to work with,” Byrds co-founder Roger McGuinn once said, echoing a sentiment probably most of Crosby’s collaborators would echo.

“I absolutely had,” Crosby says, almost gleefully, and with a hearty laugh. “Roger hates me. Almost everyone I’ve ever worked with hates me. I can be an asshole. What can I say?”

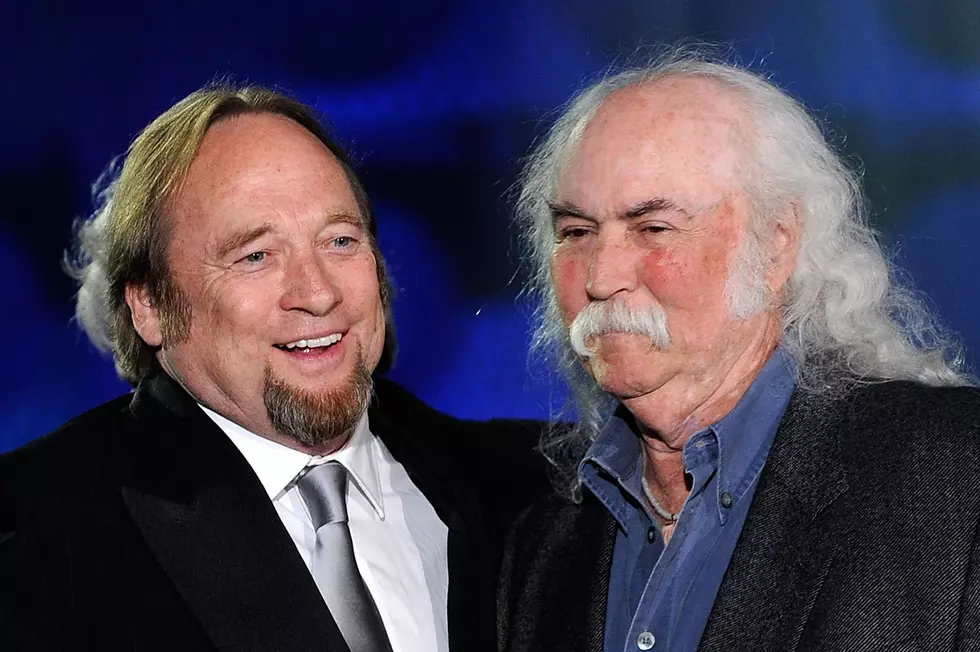

Crosby is only half-joking. After being kicked out of the Byrds, he teamed up with Stephen Stills, whose band Buffalo Springfield had imploded, and Graham Nash, who’d recently left England’s the Hollies, as Crosby, Stills & Nash.

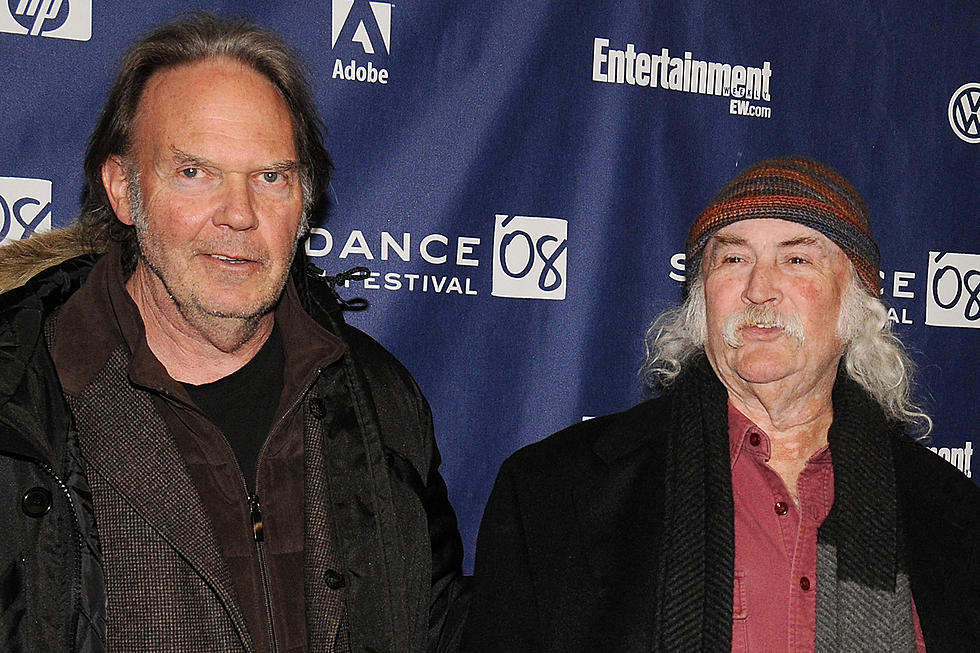

At Woodstock – and off and on for the next 40 years – they were joined sporadically by Stills' former bandmate Neil Young. The combination was dazzling, but combustible.

“I don’t butter people’s toast too much,” Crosby admits. “My nature is to be frank about things, and sometimes that’s a very uncomfortable thing for people. Also, I’ve had quite a temper for most of my life, even though it doesn’t accomplish anything.”

After one last falling out with Young, and an unusually acrimonious bust-up with longtime best friend Nash, Crosby found himself in the unusual role of solo artist.

“I think I’ve always had my own voice, but it’s always been in groups, and so you didn’t know it,” Crosby says about heading out on his own, after 50 years as, more or less, a sidekick to some of the biggest names in rock. He insists he had no trepidation stepping out as a frontman after all that time in the shadows. “None," he says. "I had been a solo act before I was in a band.

“The truth was, CSN, towards the end, wasn’t fun, and we didn’t like each other,” Crosby continues, in his characteristically frank manner. “I was not enjoying it at all. I was doing it for a paycheck, and that’s just not a good enough reason. If I had stayed there, man, it would have been the end of music for me. It’s certainly not an easy thing to do, leaving a really big, successful band. It’s kind of like diving off a cliff. But the work I’ve been doing by myself since splitting with the guys has been like diving off that cliff, and then halfway down suddenly sprouting eagle’s wings. That’s what it’s felt like.”

If that was the whole story, Remember My Name would be noteworthy enough. But the '80s were more unkind to Crosby than to any of his peers – at least those who didn’t die – and Crosby’s fall, as recounted with brutal frankness in the film, makes for an astonishing ride.

While Keith Richards reminds anyone who will listen of his bona fides as the original rock 'n' roll pirate, it was Crosby who buried a lover before the '60s had ended and who developed the sort of crippling addictions and fetish for guns that strained his personal and professional relationships to the breaking point, robbed him of his musical gifts and led to repeated run-ins with the law. Eventually, after running from an arrest warrant to his 74-foot boat Mayan, holing up with eight balls and his trusty revolver, Crosby surrendered to authorities in 1982 – looking about as bad as Richards does now at 75 – eventually serving nine months in a Texas prison.

“There wasn’t anything I really needed to get out there personally, like I’ve secretly been a woman for 20 years, because it’s all been out there,” Crosby, who has indeed been shunned by almost everyone he’s ever worked with over his long career, concedes. “But there was a definite catharsis to going back through it all.”

It helped that the film’s director, A.J. Eaton, had been chronicling Crosby’s remarkable post-CSN solo rebirth since even before the release of 2014's Croz.

“At age 70, he had this third-act renaissance, and that’s where I came into the picture,” Eaton says. “So I followed David around with a camera for about 10 years, to the point that I became a fly on the wall. The plight of the documentary filmmaker is that you have to cut things out, or you have to make some sacrifices in the process of telling the story. And David Crosby has lived an extraordinary life. If the life that he has led was in a screenplay, people would probably say, ‘That’s not possible.’ But I had this amazing access, so my mantra became that we needed to be able to ignore the details to make room to expose the truth.”

Crowe agrees that Eaton’s ability to capture Crosby unguarded was the key to setting Remember My Name apart from the usual documentary fare, and tips his hat to the first-time director.

“A.J. came at the story somewhat like a son,” Crowe explains. “He has a very strong personal relationship with David, and was artful in the way that he wanted to put David out into the world. He does not come to it with a deep river of knowledge about the 'Frozen Noses' demo tape, or rare Crosby, Stills & Nash. That’s what I get to bring as a producer. But he’d done the most difficult work of all, which is to become invisible. A.J. came to the story with the sense of 'Let’s go on this trip with David, and as we go along this journey on a tour that David may or may not come back from, let’s tell his story.' That was both magical and sad, because you get right in there, with David pouring his heart out, raging against the coming night, without it ever becoming a dark experience. Instead, it’s emotional and transcendent, because you get the idea that this guy is going to tell you all this stuff because he may not be around, but there’s a joy in all that he’s discovered and wants to share.”

Crosby was also adamant that the film not gloss over the many band bust-ups or crushing personal lows he’d experienced during his long career.

“They see themselves as a pretty picture that they’re supposed to transmit to the public,” Crosby says of the way he sees his peers set on perpetuating a false image of themselves to the public, especially in the recent spate of documentaries chronicling the golden age of rock 'n' roll. “They try very hard not to tell the truth. They polish it, and they take all the dirty bits off, and put a nice bow on it and say, ‘Isn’t he nice? Isn’t he cute?” And it’s just bullshit. I just didn’t want to go down that road. There’s been a million documentaries and films and books about CSNY; everybody knows about it already. So I didn’t really feel that there was any need to talk about it, though I certainly didn’t want to slag my ex-partners in either the Byrds or CSN. I like them all. I’ve got no bad feelings about them in my heart whatsoever. But I just didn’t think that was where the meat of the matter was, anyway.

“Look, in order to do this right, I had to step outside of myself and look at myself as a thing to be studied and to be presented in this documentary,” Crosby continues. “I certainly didn’t want to show you an incomplete or dishonest picture. However rough it may be to watch, I wanted it to be honest. And I think we did that. And it was a hard thing to do, so I’m proud of it."

Watch 'David Crosby: Remember My Name' Trailer

Crowe, who was already committed to other projects while the documentary was in production, but who agreed to interview Crosby after much cajoling by the legend – “It really helps to have a friend like Cameron who is a merciless interviewer, because there was nowhere to hide,” Crosby jokes – agrees that there was no need to retell the same old tales of the Woodstock generation, or prance through the usual talking heads to help tell the tale, but as a storyteller he also felt the urge to push the boundaries of the genre.

“There’d been a VH1 documentary, and a lot of books had been written, but it was all very sanitized,” Crowe explains. “David’s books were of the same spirit that what we wanted capture with the movie, but they were a long time ago. And the whole notion of parading people from David’s past through. ‘Oh, look, he hasn’t aged well. He’s aged great. She’s amazing.’ That always takes me out of the story. Plus, the idea of sending a million letters, begging people to talk. Who needs to do that? So we wanted to break the genre, and to set a standard for the interviews with David, because if you’re going to spend the time to make a film with a dude who stood on the stage of Woodstock – one of the few still alive – he’s got to go there. And he does! So why not let David tell you his story, and let the audience add it up? Why not let even the guys in his bands add it up?”

“Truthfully, man, I don’t think there’s really much of a choice,” Crosby explains. “If you choose to just present a carefully manicured version of yourself, and avoid telling anything except the cute little fairy-tale story, then nobody knows who the hell you are, and they never will. Plus, too many documentaries are made by just going out and interviewing everybody that you ever worked with who’s famous. You have them say how wonderful you are, and then you can use their name in the advertising. And that’s it. It’s done. It’s a surface job, and everyone knows it. We didn’t want to do that. We felt that I’ve had a checkered history – that there was good and there was bad, and there was everything in between – and that if we were going to talk about it at all, we were going to talk about the actual stuff in as truthful a manner as possible. Cameron felt that way, and A.J. felt that way, and since I felt that way also, we had a unity of purpose. We had an agreement between us, very clearly, about what was important and how to go about it.”

Still, even though Crosby was thrilled with the rapturous response the film received at Sundance, and its theatrical run this summer was a success, he was initially worried he’d gone too far.

“What I’m afraid of is that it will be too shocking,” he said before the festival screening. “My hope is that people will say, ‘God. They laid this guy right out here.’ If they react that way, then I’m going to be the happiest motherfucker you know. If they’re a little shocked by it, and they go, ‘Wow. Didn’t really want to know that.’ Well, then, we probably went too far.”

Crowe, however, knew better.

“Obviously, you don’t know, because you never know,” Crowe admits. “But like with Fast Times at Ridgemont High – which had a scene with a guy masturbating in the bathroom and a scene with a blow-job lesson – as the movie started to get closer to release, I started to panic, because I started to think, ‘Oh, my god, what have we done? This is so personal and corrosive and raw.’ But then, the first time we showed it to an audience, the most personal stuff, that I was most fearful about being too raw, was what they loved. That’s what went through the roof. I saw it happen in the audience. And I realized that which you fear the most, that you think is too personal, is often going to be the thing that touches people most directly.

"And that’s what happened with this film. Because David never asked for final cut, which is a very bad-ass move of him, since with projects like this the subject always has the fucking final cut! And so that most personal stuff? They see the twinkle in David’s eye, and they see him really thinking and feeling it, and it’s authentic. And you know what? They get him. They understand him. Because we just put the camera on Croz, and they go through a journey with him. They know his music, but they didn’t really know who this guy was. But now they do.”

“I think I’m going to wake up in the morning and go, ‘Oh, this has been a big dream,’ Eaton says of the response. “But we were truthful, and we treated David’s trust and what he gave us in the interviews wisely.”

Ultimately, though, Crowe feels it’s the love story between Crosby and his wife Jan that bookends the film, and is the thread that holds the story together throughout, that is the most unexpected thing about his experience in making Remember My Name.

“That’s the surprising thing that happened when we started showing the film: That there’s this gentle thread that runs through the movie, the emotional experience and the love story, of his relationship with his wife Jan, that peaks on this beautiful hug that she gives him near the end of the film. Every time I’d watch that hug in the editing room, I’d say, ‘Best shot in the movie!’ Who doesn’t want to be hugged like that? It made us emotional every time. But I didn’t know how strong that love story was going to come across to an audience, but it really did.”

“The whole experience has been very daunting -- to put my life out there in front of people,” Crosby admits. “So what I wanted to know was this: Did we make people feel anything? The audience at Sundance, well, they were film people, and we did get them. And it was wonderful. But we still weren’t sure. So we went down to Salt Lake, and it just knocked their asses in the dirt. They completely loved it. The reception was as warm as you could possibly ask for it to be. And that’s what really good filmmakers do. They make you feel stuff. They set you up with imagery and music and words and ideas and emotions, and they take you on a little voyage. If they’re really good, then you feel things.

"I don't know how much time I’ve got," says Crosby, who at 78 is definitely feeling his mortality. "But the significant thing is not how much time you have, but what the fuck are you going to do with that time? Now, to me, I can only make one kind of contribution in this world. I am only really good at one thing. I’m a good singer and a good writer. So that’s the contribution I can make. Because music’s a lifting force. It makes things better. Just the same way that war drags people down, and makes things worse, and brings out the very worst in humanity, so does music bring out the very best. Okay, so music’s the one contribution I can make. It’s the only place I can lift. It’s the only thing I can do that makes things better. So that’s what I should be doing with my time, however much time I have, whether it’s two weeks or 10 years. Spending time with my family, of course, and making music. Those are really the only two things that I’m responsible for, and that I feel a really pushing need to accomplish. And I do feel a very strong push.”

Top 100 '60s Rock Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock