David Byrne Says ‘American Utopia’ Is ‘Incredibly Liberating': Exclusive Interview

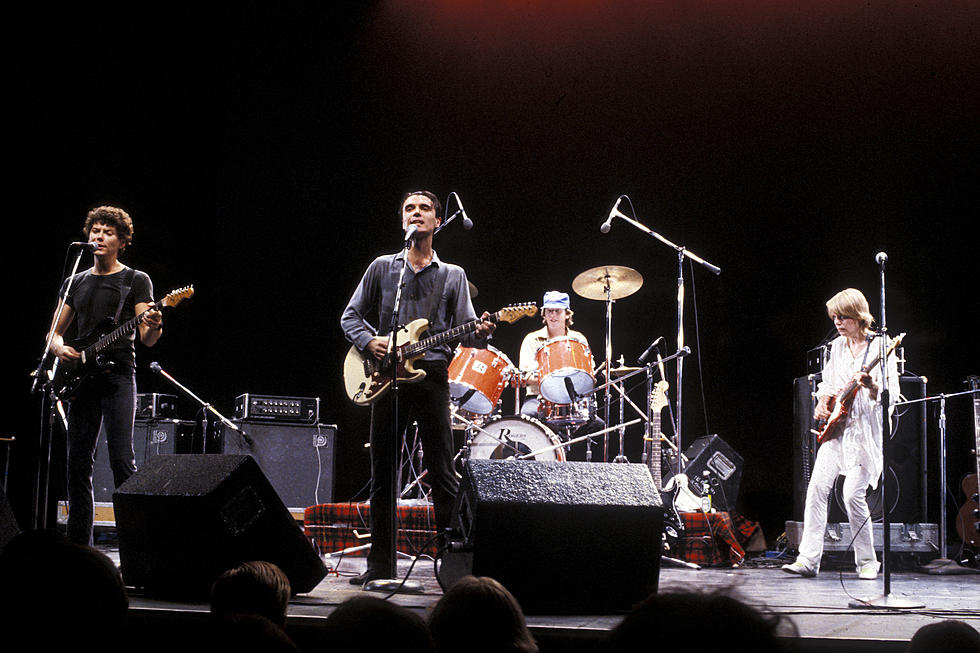

David Byrne is often considered one of rock’s most arty icons. In the late '70s and '80s, with his band Talking Heads, Byrne went for introspective, existentialist and weird. Maybe the epitome of this artiness came with their 1984 concert film Stop Making Sense. Directed by Jonathan Demme, the movie had Byrne in an oversized suit and the rest of the band in muted, gray outfits.

With the concert experience American Utopia, which just ended a month of shows in Boston and debuts on Broadway this coming weekend, Byrne continues that trend, including his love of gray. The show features 12 musicians free of cords and wires. No microphone stands, amplifiers, guitar pedals or drum kits clutter the stage. Wireless technology allows the band to sing, play, dance and wander between each other and jump in and out of the groove through a chain-link curtain that boxes in the stage.

It all seems very, you know, arty. To explain how he got here, David Byrne tells UCR about American Utopia, Broadway and his reputation as an ironic songwriter.

The show doesn’t have a plot per se, but you say is has an arc. How do you describe the journey of American Utopia?

I see it as the journey of a character who is me but not me, because it’s not necessarily biographical. He starts off within himself wondering how to be in the world, what's the right thing to do, how you relate to other people. It's all kind of a mystery to the character. Then this person finds himself within this little community -- in this case the band -- and that allows him to come out of his interior a bit. Then by the end, this person and the band are engaged in the wider world, getting involved beyond their own bubble.

As you put together the set list, as you thought about the songs on the American Utopia LP, Talking Heads catalog and all your other solo albums and collaboration, how did you figure out what worked with the arc?

I had a little bit of an idea of what would work. I knew “Psycho Killer” wasn't going to be in the set. I knew that wasn't what the show was about. And there was a song from the new album that we were doing and I thought, “Hmm, this doesn't really work either,” so we swapped it out for something old. We kept looking for things that would help the story a little bit.

If people have seen the American Utopia tour or your performance on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert, will they have a good shorthand to understand the Broadway show?

Yes, some of that was in the tour, some of that arc. But this will make things a little more explicit without being too on the nose about it.

Watch David Byrne Perform on Late Show With Stephen Colbert

Do you go to a lot of Broadway productions?

I go to a fair amount of theater. Some of it is on Broadway, but not all of it. I did see What the Constitution Means to Me, which is exactly what it's about. [Laughs] I've seen other theater in Brooklyn and other places that sometimes end up on Broadway.

So why present this as a Broadway production as opposed to an extended run of concerts at the Beacon Theater or some other traditional venue for pop music?

That wouldn't be a challenge. It wouldn't be so exciting. It was offered, the idea of going out and doing more tour dates, but I had done that. I wanted to take up the challenge and see how the show would be in a context where audiences bring in slightly different expectations.

What's the difference between a concert and American Utopia?

One simple difference will be there will be less standing up the among audience members. And I think one difference is theater people may expect there to be an idea.

Maybe a thesis statement?

Yes, a thesis statement or an expectation that the material will be presented in some way that's emotionally engaging. Something more than, “Hey, here’s a bunch of songs.”

Do you worry that the repetitiveness, the fact you will do the same set and choreography night after night, will drain some of the spontaneity from the show?

I can tell that this is something some people are worried about. I think there is no problem doing something that is scripted, that is worked out, as long as it's still emotionally engaging. If it's emotionally engaging for the audience member, it tends to be for the performer as well. I have seen shows that are so tightly choreographed and staged that you don't feel anything other than seeing all of the skill involved to pull it off. My hope is that we don't fall into that trap. But spontaneity isn't always the best way to communicate an idea or emotion. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't. People from the music world tend to think that if something is spontaneous it's more real or authentic or from the heart. There might be some truth to that. But watching two people have an argument in a restaurant can be spontaneous but not emotionally engaging. It can be more like, “Get me the fuck out of here.” [Laughs]

What was the impulse in cutting all the strings and abandoning traditional staging of a rock show?

Part of it was about movement. I knew that I could get everybody moving, I would have something different. I would have a stage completely cleared, no wires and water bottles, no mic stands or wedges or anything else. It's all about us and how we move and how we relate to one another. Then I realized that's what people are interested in, seeing other people and seeing how they relate to one another. That's what's interesting to us as a human species. We're generally not interested in platforms and various bits of gear. And then there was this huge knock-on effect. It was incredibly liberating for us. It allows democratization. You can't normally have a drummer in a band come forward to the front of the stage so you can see what this person does. In this case, we could do that because there are six drummers and they can move to the front and I can move to the back. It's not like they're taking a solo but they're up front so people can see what they do. Everybody in the whole group gets some moments where they are the focus of attention.

You are often thought of as highly ironic or sardonic or detached, but I find so much of your music deeply earnest. I find that here in American Utopia. You wrote in an open letter about this show that the title is not ironic and the set list seems to focus on optimism. Why is it important to point out the show isn’t ironic?

The songs aren’t cynical. This is true. It may be a little hard to believe because people do tend to associate me with a lot of ironic stuff, using an ironic point of view. But I think people get that this is something different.

People also think of you as very arty, but from the start of Talking Heads through American Utopia, it seems like you have been happy to work in popular music, which has a restrictive form, a four-minute, Top 40 song form. Is this a correct assessment?

I do other things too, but for a performance or a group of songs for a record, I’m happy to be restricted to that form. I want to push the boundaries, but I accept the form as a popular art form. Lots of people have proved this, but there is plenty you can do inside that form.

Talking Heads Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock