How David Bowie Reconnected With Brian Eno for ‘Outside’

David Bowie bid farewell to the past with 1990's Sound + Vision tour, but that didn't mean he completely loosened himself from his own history. In fact, Outside, released on Sept. 26, 1995, was sparked by a chance meeting with former producer Brian Eno at a wedding a few years before.

Bowie rediscovered a lingering creative connection with Eno, though it had little to do with their shared triumphs on the Berlin Trilogy of the late '70s. "We realized we were both interested in nibbling at the periphery of the mainstream rather than jumping in," Bowie told USA Today in 1995. "We sent each other long manifestos about what was missing in music and what we should be doing. We decided to really experiment and go into the studio with not even a gnat of an idea."

In this way, David Bowie was able to gird his latest experiments with a foundational element of his legend, recalling landmark projects like Low, 'Heroes' and Lodger without being held hostage to their form. "It's like a painter repeating significant motifs in his own work, creating a personal vocabulary," Bowie added. "I now have my own currency, 24 albums worth."

From these initial studio improvisations grew a string of darkly eccentric characters, which Bowie and Eno then assembled into a stream-of-consciousness, turn-of-the-millennium tale titled The Nathan Adler Diaries. They'd be brought to life, in part, by a band that also held some connections to Bowie's earlier personas. Pianist Mike Garson had been part of the Aladdin Sane album, while guitarist Reeves Gabrels was in Tin Machine with Bowie.

“As for musicians, it was important to choose those who were not weighed down with musical cliche, who had terrific control over their abilities, yet were a bit loony,” Bowie told MTV. Eno got them into the proper mindset by passing out cards with oblique messages like: “You are a disgruntled ex-member of a South African rock band. Play the notes they won’t allow.”

Listen to David Bowie's 'Hallo Spaceboy'

The results built in modern-day textures like techno, grunge and industrial over the electronic soundbeds that powered Bowie's earlier Eno collaborations. A bolstered David Bowie, years after the commercial success of Let's Dance, seemed to have found his footing once more. In fact, as society hurtled toward the end of an era, the jittery paranoia and strangely unmoored feel of Outside felt like the beginning of something big for Bowie.

"The momentum gathers as we approach the end of this cycle of 100 years, a huge anguish that everything will change," Bowie told the Chicago Tribune. "I wanted to make a record that reflected those anxieties, a state of moral, spiritual and emotional panic, with people breaking off into small groups to feel some sense of community."

He planned, at that point, to release a related album annually through the conclusion of the '90s. "This is a once-in-a-lifetime chance, by a narrative device, to chronicle the final five years of the millennium," Bowie said in 1995. "The over-ambitious intention is to carry this through to the year 2000."

But Bowie, in yet another nod to his own backstory, ended up changing his mind. Instead, the electronica-focused Earthling didn't arrive until 1997, and it wasn't a direct follow up – though Gabrels and Garson participated.

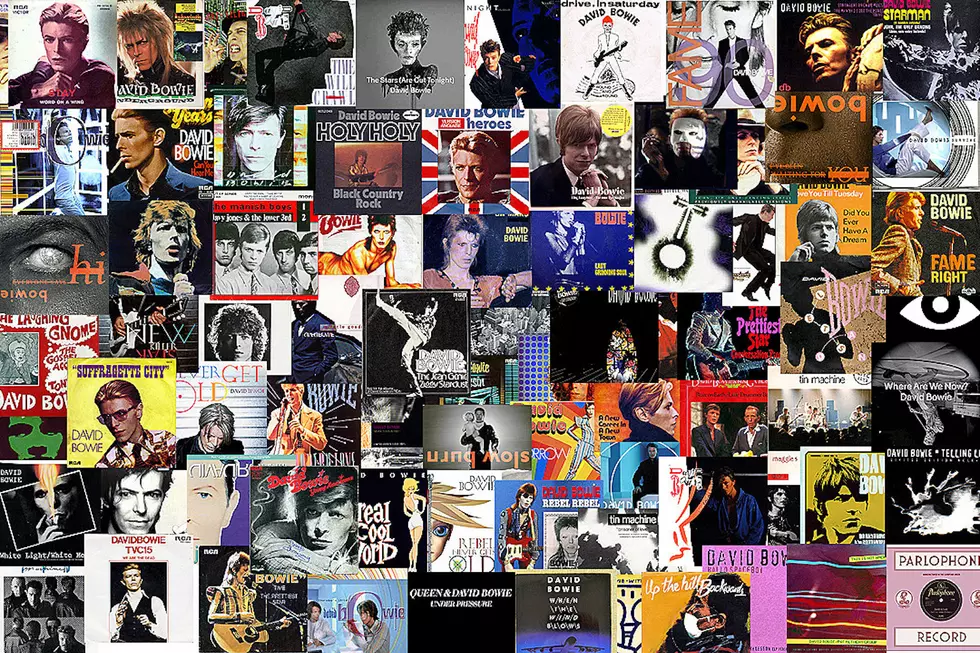

Every David Bowie Single Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock