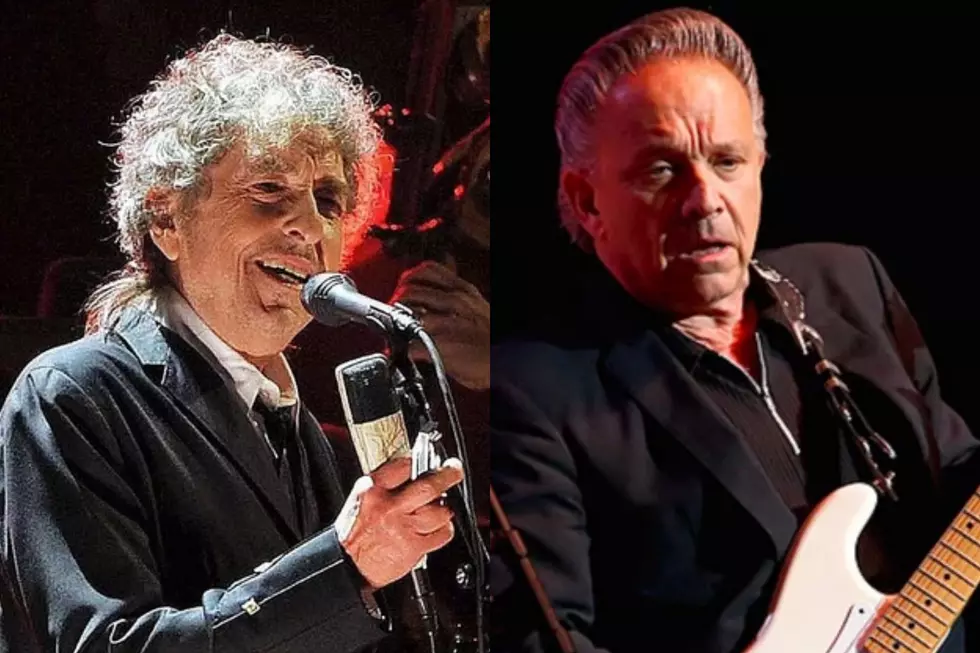

Did Fans Really Boo Because Bob Dylan Went Electric at Newport?

Of all the memorable events that took place in rock 'n' roll history in 1965, only one was so controversial that practically every aspect of it is still being analyzed and debated all these years later.

But one thing is for certain: On July 25, 1965, Bob Dylan bid goodbye to his folk roots with an electric set at the Newport Folk Festival in Newport, R.I.

Was it a resounding booing or just a few people expressing their displeasure? And what was the story about Pete Seeger wanting an axe? It’s rock’s version of Rashomon; everybody’s perspective is different.

Dylan had first appeared at Newport two years earlier, shortly after the release of his second record, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. There, he had the stamp of approval of Joan Baez, who catapulted to fame on the strength of her performance at Newport in 1959, and it led to his meteoric rise within the folk community, where he was hailed as the voice of the Civil Rights Movement for songs like “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Only a Pawn in Their Game.”

His fourth album, Another Side of Bob Dylan, showed him moving away from topical songwriting. Although it featured, like the others, only his vocals, acoustic guitar and harmonica, the tracks like "My Back Pages” and “All I Really Wanna Do” reflected a more personal and introspective Dylan.

Bringing It all Back Home, released in March 1965, took the next step in showing that he was looking to branch out. The entire first side was recorded with a makeshift rock band comprised of session musicians while the second half was, apart from a chiming electric guitar in “Mr. Tambourine Man,” a continuation of his acoustic beginnings.

Still, he agreed to play Newport. The week leading up to the festival, he put out “Like a Rolling Stone” which broke all existing rules for its subject material, how a hit single could sound and how long it should be. But to the folk scene, he was the same Dylan, playing a few songs at a songwriting workshop on the Saturday. Then, after hearing that Alan Lomax, whose landmark field recordings had helped popularize folk and blues, made some disparaging remarks about the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, he decided to shake things up.

He recruited organist Al Kooper, three members of Butterfield’s band — guitarist Michael Bloomfield, bassist Jerome Arnold and drummer Sam Lay — and pianist Barry Goldberg, and rehearsed that night at the house of festival founder George Wein. Bloomfield and Kooper had played on “Like a Rolling Stone.”

But Dylan didn’t tell anybody what he had planned to do. After much confusion as they were setting up and an awkward introduction by Peter Yarrow of Peter, Paul & Mary — "The person who's coming up now is a person who has, in a sense, changed the face of folk music to the large American public because he has brought to it a point of view of a poet. Ladies and gentlemen, the person that's going to come up now has a limited amount of time. His name is Bob Dylan." — the makeshift band launched into a take on “Maggie’s Farm” that was more rushed and raucous than the recorded version. They played two more songs, “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Phantom Engineer” — which became Highway 61 Revisited’s "It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry" — before Dylan said, “Let’s go, man. That’s all” to the band.

So what happened? That depends on whom you ask. Some say there wasn’t much booing; others say it was all-consuming. Even the existing audio from the festival shows there’s some dissent but it’s too crude to be conclusive.

But why were they booing? Was it at Dylan for “betraying” folk music? That’s been the conventional wisdom. “There was anger, there was fury, there was applause, there was stunned silence, but there was a great sense of betrayal,” critic Greil Marcus said. “As if something precious and delicate was being dashed to the ground and stomped. As if the delicate flower of folk music, the priceless heritage of impoverished black farmers and destitute white miners, was being mocked by a dandy, with a garish noisy electric guitar, who was going to make huge amounts of money as a pop star by exploiting what he found from these poor people. That’s a very crude, but I don’t think all together inaccurate summation of something very complex.”

The most popular alternate theory suggests that many people were upset at the poor quality of the sound, which is where Pete Seeger comes in. Over the years word spread that Seeger was so incensed by Dylan playing rock that he was storming around backstage looking for an axe to cut the cables. But as you can see in the video above, Seeger says that he had no objection to the music, but that there was so much distortion that cutting the cables was the only solution. And even Seeger’s claims have been contested by those who believe he only changed his story once he realized that he was on the wrong side of history.

Watch ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ From Newport

Kooper believes that the boos were because of the short set, telling City Pages, “What happened was, everybody played like 45 [minutes] to one hour-length sets at Newport. Bob played 15 minutes. And he was the headliner of the whole thing. That's why people were upset. And then he played like three electric songs. Very Bob.”

Yarrow returned to the stage and, on the microphone, pleaded with him to return. Dylan relented long enough to play two solo acoustic songs, “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” and “Mr. Tambourine Man” before leaving the stage again.

Four days later, Dylan recorded “Positively 4th Street,” a song widely believed to be a kiss-off to the New York folk scene, which is centered around 4th Street in Greenwich Village. It reached No. 7 on the Billboard Hot 100.

But there was little ambiguity a month later when, at the tennis stadium in Forest Hills, Queens, Dylan decided to split the concert in half, starting with a solo set, which was well-received, and concluding with a full band consisting of Kooper, bassist Harvey Brooks and two members of an unknown Canadian group called the Hawks, Robbie Robertson and Levon Helm. The New York Times’ Robert Shelton, whose 1961 review of a Dylan concert is considered to have launched Dylan’s career, wrote, “The young audience’s displeasure was manifested at the end of most of the numbers, by booing and shouts of ‘we want the old Dylan.’ The young star plowed valiantly on, with the sort of coolness he has rarely displayed on stage.”

Calling the crowd “rude,” “immature” and “noisy young boors,” he couldn’t help note the positive reaction given to “Like a Rolling Stone,” which by now was a hit. “Evidently the hostility extends only toward things with which they aren’t familiar,” he sneered.

Pete Seeger Clarifies His Story

This song-and-dance with his audience continued over the course of the next year. The audience would applaud during the opening acoustic set and boo the electric. Five months after Newport, he said at a press conference in San Francisco that he was surprised by the negativity. “I did this very crazy thing. I didn't know what was going to happen, but they certainly booed, I'll tell you that. You could hear it all over the place. I don't know who they were though, and I'm certain whoever it was did it twice as loud as they normally would. They kind of quieted down some at Forest Hills although they did it there, too. They've done it just about all over except in Texas – they didn't boo us in Texas or in Atlanta, or in Boston, or in Ohio. They've done it in just about – or in Minneapolis, they didn't do it there. They've done it a lot of other places. I mean, they must be pretty rich, to be able to go someplace and boo. I couldn't afford it if I was in their shoes.”

This came to a head on May 17, 1966 and the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, England. After “Ballad of a Thin Man,” someone in the crowd shouts “Judas” to the crowd’s delight. Dylan shot back, “I don’t believe you. You’re a liar!” and then told his band to “play it f—ing loud.” On that cue, drummer Mickey Jones slammed down on his snare drum as the band roared into “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Following the tour, Dylan retreated to his home in Woodstock, N.Y. On July 29, he got into a serious motorcycle accident and decided to take a break from public life. Dylan wouldn’t return to the road until his celebrated 1974 tour with the Band, by which point the rest of the world had caught up with him.

Bob Dylan Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock