How the Allman Brothers Band Tried to Carry On With ‘Eat a Peach’

After struggling to find an audience with their first two studio LPs, the Allman Brothers Band finally achieved a commercial breakthrough with 1971's At Fillmore East. But just as it seemed they were getting some momentum going, tragedy threatened to derail the group completely.

The Allmans' rise to fame was fraught with complications from the start. As the Fillmore record erased their debt to Capricorn Records and padded their bank accounts, the band members grew more embroiled in unhealthy habits — to the point that, toward the end of the year, guitarist Duane Allman and bassist Berry Oakley booked themselves into rehab, along with roadies Robert Payne and Joseph "Red Dog" Campbell. It didn't really help their addictions — the concept of "rehab" was still very much in its infancy at the time — but hopes were high as they entered the studio to record their third studio LP.

Sessions for the album were only a few weeks along when, on Oct. 29, 1971, Allman used a little studio downtime to head out for a motorcycle ride. Speeding through Macon, Ga., he arrived at an intersection where a flatbed truck was stopped — and suffered numerous major internal injuries when he swerved to avoid hitting it. Despite doctors' best efforts, Allman died at the tragically young age of 24 — depriving the band of its leader and creative spirit while it was still establishing its identity.

Deeply shaken, the surviving members of the group briefly considered folding, but quickly determined that the best way to honor what they'd started with Duane was to carry it forward. Fortunately, there was no shortage of talent left in the lineup: Allman's brother Gregg held down vocals and keys while maintaining the family tradition and guitarist Dickey Betts reluctantly added electric slide to his duties to cover for Duane's absence, while the rhythm section — bassist Berry Oakley, percussionist Jai Johanny Johansson and drummer Butch Trucks — maintained a steady bottom end.

Betts, in particular, offered creative leadership at a juncture when it was sorely needed. "It very easily could have ended right there, but Betts pulled it out of the fire," band associate Thom Doucette later argued in One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. "A lot of people do not understand how really smart and connected Dickey is, because of his demons, which can take over."

"We thought about quitting, because how could we go on without Duane?" admitted Trucks. "But then we realized: how could we stop? We all had this thing in us and Duane put it there. He was the teacher and he gave something to us— his disciples— that we had to play out. We talked about taking six months off but we had to get back together after a few weeks because it was too lonely and depressing. We were all just devastated and the only way to deal with it was to play."

Listen to the Allmans Perform 'Ain't Wastin' Time No More'

The band was short on material when it made the choice to soldier on; fortunately, they'd already tabbed some leftover tracks from the Fillmore East recordings to round out the track listing for the new LP, including a half-hour version of their "Mountain Jam." Although Betts and Trucks would both later claim it was one of the worst performances of the song, it included Duane, so it made the cut — along with Fillmore covers of Elmore James' "One Way Out" and Muddy Waters' "Trouble No More."

Sandwiching the live tracks were a series of studio performances, some of which were already in the can before Duane's death. To round out the record, Betts contributed the nine-minute "Les Brers in A Minor," while Gregg added a pair of tracks heavily influenced by Duane's passing: opening cut "Ain't Wastin' Time No More" — which he'd later say he finished writing for Duane because "it was the only thing I knew how to do right then" — and "Melissa," a sweet ballad Gregg had composed years before that had long been one of his brother's favorites.

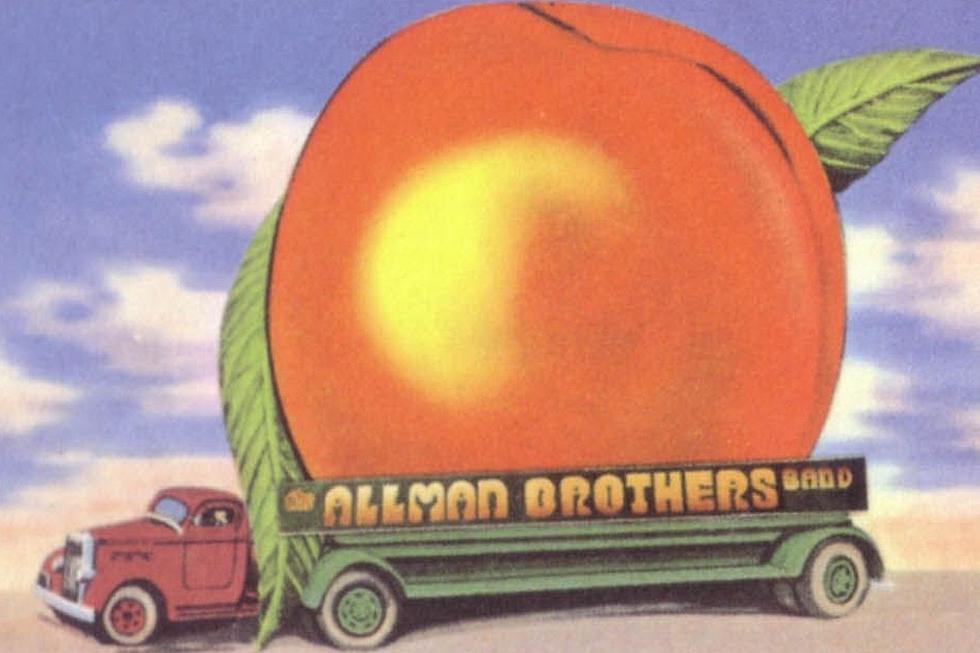

The album, titled Eat a Peach, arrived in stores on Feb. 12, 1972, and however piecemeal its construction might have been, the end results still held together cohesively — and the fans turned out in greater numbers than ever. Peach shipped gold, rose to No. 4 on the Billboard chart, and added a number of FM mainstays to the growing number of Allmans rock-radio hits — all while the band shouldered the difficult burden of going back out on the road as a five-piece.

The group would face no shortage of hard times in the months and years ahead — Oakley also died before the end of the year, succumbing to injuries sustained in a motorcycle accident with painful parallels to Allman's death — but Eat a Peach proved they could not only continue in Duane's absence, but flourish along the way. More than four decades after its release, it remains a classic in a discography studded with distinguishing achievements.

And as for its somewhat cryptic title? Urban legend has long suggested it's a reference to Duane hitting a peach truck with his motorcycle — and added that the watermelon truck pictured elsewhere in the artwork prophesied Oakley hitting that type of truck when he died — but it simply isn't true. Fittingly, the title did come from Duane, but it isn't grim or ghoulish; instead, it's a reference to a sexual wisecrack he made, coupled with a T.S. Eliot poem.

"Duane didn’t like to give simple answers, so when someone asked him about the revolution, he said, 'There ain’t no revolution. It’s all evolution,'" Trucks explained in One Way Out. "Then he paused and said, 'Every time I go South, I eat a peach for peace ... the two-legged variety.' That stuck out to me, so I told [label boss Phil Walden], 'Call this thing Eat a Peach for Peace,' which they shortened to Eat a Peach."

Allman Brothers Albums Ranked

Tedeschi Trucks Band Discuss Their Influences

More From Ultimate Classic Rock