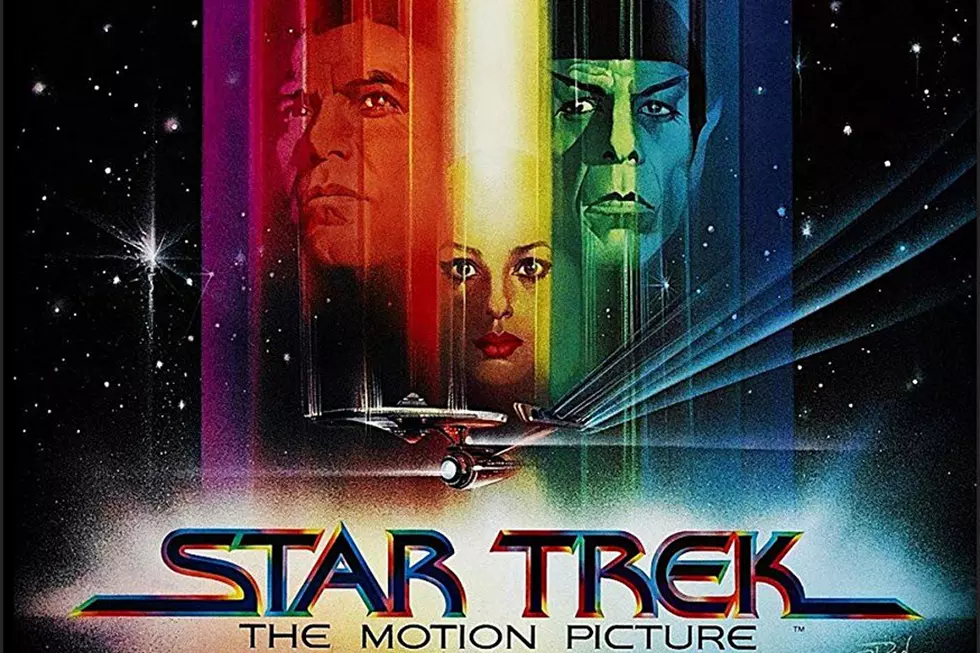

40 Years Ago: ‘Star Trek’ Boldly Goes to the Big Screen

When Star Trek: The Motion Picture arrived in theaters on Dec. 7, 1979, it came 10 years, six months and four days after the last episode of the original series. For creator Gene Roddenberry and the actors who’d become household names at the end of the ‘60s, it had been a decade of frustration.

Roddenberry had wanted to take Star Trek to the silver screen as early as the second season but Paramount, owners of the franchise, didn’t believe in the show, and axed production the same year. Another season had followed as a result of a letter-writing campaign from fans – but, with little support from the producers, the viewer numbers had sealed the show's fate.

Its true success had come when Paramount sold Star Trek into syndication, resulting in nearly 150 territory purchases and generating a new explosion of support. When the first fan convention sold 10,000 tickets in 1972, Paramount began to think again. Three years later Roddenberry was given a budget to start work on a movie with the working title Star Trek II.

He came up with a script, "The God Thing," which saw Captain James T. Kirk (William Shatner) gathering Spock (Leonard Nimoy), McCoy (DeForest Kelley) and the crew of the USS Enterprise’s to take on a massive alien being that turns out to be a computer programmed to wreak revenge on behalf of its creators, a race who’d been thrown out of the galaxy for their evil.

Paramount didn’t like it. Instead, big-name science fiction writers including Ray Bradbury and Theodore Sturgeon were approached, and ideas such as snake-like aliens changing the universe’s timeline and the Enterprise using time travel to save a crumbling universe were mooted. The project was put on hold, then restarted, while new writers including George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola were approached. Roddenberry also approached Coppola and Steven Spielberg, among others, about directing, but everyone refused; perhaps because of the movie’s relatively low budget of $8 million.

Eventually, a story named "Planet of the Titans" was adopted and the production began coming together in October 1976. By March 1977 a script had been delivered to Paramount, who rejected it, describing it as “a script by committee.” That led the studio to decide that Star Trek wasn’t movie material, and would be better off returning to TV.

So, in 1977, Roddenberry began work on what became known as Star Trek: Phase II. By that time, Nimoy had lost confidence in Paramount and refused to sign up for the series. A new Vulcan named Xon was invented to replace Spock, and the characters of Commander Decker and Navigator Ilea were added. The pilot episode was named “In Thy Image” and featured a long-lost probe returning to Earth after achieving sentience in its travels. It bore a marked resemblance to an original series episode titled “The Changeling,” where a probe called Nomad causes trouble as it tries to learn about the Enterprise and its crew. When a polished teleplay of “In Thy Image” was presented to Paramount, the studio loved it, saying it was good enough to be a movie.

Star Trek: ‘The Changeling’ Episode Trailer

Around that time, Spielberg’s film Close Encounters of the Third Kind became a hit. Seeing its success, combined with the triumph of Lucas’s Star Wars in 1977, the producers told Roddenberry to shut down Star Trek: Phase II and return to work on a film instead. They’d pulled the plug on the TV show around 15 days before shooting had been scheduled to commence.

The announcement was made in March 1978 at the second-biggest press conference ever held at Paramount Studios (the biggest had been for Cecil B. DeMille’s announcement of The Ten Commandments). Robert Wise, known for such science fiction films as The Day the Earth Stood Still and The Andromeda Strain (among others), was confirmed as director of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, to be made with a $15 million budget.

“Here was an opportunity that was really unique,” Shatner said in 2017. “A television show was going to make first-run movies. I don’t think it had been done before. And getting Robert Wise – the great editor and director of these large films – was a huge coup. So, everybody thought it was going to be terrific.”

Wise knew the genre but he didn’t know Star Trek, and that was to become an issue as work continued. Although he'd already taken a great step – advised that you couldn’t have a Star Trek movie without Spock, he'd persuaded the producers to renegotiate with Nimoy, who agreed to return, despite reservations. That meant writing the Vulcan into a script that hadn't previously included him. Meanwhile, the Decker and Ilea characters were preserved from Phase II.

As “In Thy Image” was converted to a movie script, Wise’s interest in visual effects began to concern the actors, who felt that the character-led approach of the original series was being diluted. The start of filming was delayed as disagreements continued between Paramount, Roddenberry, Wise, the writers and the cast. There was also doubt over the ending, where V’ger, the intergalactic super-being that threatens Earth, is revealed to be a 20th century Voyager probe made almost omnipotent by an alien race who only wanted to help it complete its mission, learn all that is learnable and return the information to the creator.

Out of the original 150 pages of the script, just over a dozen remained intact by March 1978. Even when shooting began on Aug. 7, 1978, the cast were regularly told not to learn new lines because they’d almost certainly change; adjustments were marked by the hour rather than the day. Despite constant issues with props – the transporter beam bases melted people’s shoes, the wormhole sequence took weeks to get right, the light on Ilea’s throat caused her a mild burn – coupled with constant rewrites, the actors remained in good spirits. Wise, despite the pressure of overseeing work on 11 of Paramount’s 32 sound stages (no movie had used so many), almost never lost his temper. He also had the sense to consult with the actors, mainly Shatner, about characters they knew better than he did.

“As the story developed, everything worked until the very end,” Harold Livingston, writer of the original “In Thy Name” script, later recalled. “How do you resolve this thing? If humans can defeat this marvelous machine, it's really not so great, is it? Or if it really is great, will we like those humans who do defeat it? Should they defeat it? Who is the story's hero anyway? That was the problem. We experimented with all kinds of approaches...we didn't know what to do with the ending. We always ended up against a blank wall.” It was later reported that the concept of a living machine was only found to be agreeable after a senior scientist at NASA happened to say at a press event that he believed such a life form was possible.

Principal filming wrapped on Jan. 26, 1979 after 125 days. Paramount wanted a Christmas release date, but since post-production was expected to take twice as long as shooting, and everyone involved in the project now understood that everything took longer than expected, there was already the chance that the deadline would be missed. Worse, the firm hired to produce the visual effects was found to be incapable of delivering a Star Wars level of engagement, and were fired after $5 million had been spent and only a few seconds of screen time secured. With just nine months to go, work started from scratch, costing another $5 million.

“We knew it was going to be a Herculean task, and it was going to be 24 hours a day for seven months straight," effects expert Douglas Trumbull said in 2019. "The exhibitors who had paid in advance had banded together to get ready to file a class-action lawsuit against Paramount Pictures, to actually prohibit blind bidding in the future. So there was a lot at stake, and a lot at stake for the industry as a whole. Paramount decided to just make sure there was no chance at all that this movie wouldn't get finished on time."

Inevitably, corners had to be cut. When Wise personally carried the recently-completed print of Star Trek: The Motion Picture to the premiere at the K-B MacArthur Theater in Washington, D.C., it had never been screened to a test audience, and was regarded by many as just a rough cut of the movie they’d wanted to make. “On a scale of one to 10, the anxiety level on that film fluctuated somewhere between 11 and 13,” producer Jeffrey Katzenberg said later (he was another member of the team who’d quit and been persuaded to return). “Never in the history of motion pictures has there been a film that came closer to not making it to the theaters on its release date.”

"It was a really close call," Trumbull said, noting that his visual effects tasks had landed him in hospital. “That was probably one of the biggest close calls in movie history, where all the reels of film were coming out of the lab, and there was one final reel that wasn't quite finished yet, and it was wet film shipped to the theaters at the last minute."

Complete with Jerry Goldsmith’s soundtrack (inspired, he admitted, by John Williams’s sweeping music for Star Wars), Star Trek: The Motion Picture set box office records on the weekend of its release, going on to gross $139 million worldwide and becoming the fifth-biggest selling movie of 1979 in the U.S. It had eventually cost $46 million to make, meaning that, although it turned a healthy profit, it hadn’t been the money-spinner Paramount had hoped for.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture - Trailer

Star Trek fans, of course, were grateful to see Kirk, Spock, McCoy and the others back after 10 years away, so they perhaps curtailed some of their criticism. The press, however, was more curt. The drawn-out visual effects sequences – including a long tour around the new USS Enterprise (a fan-favorite), and a slow cruise through the physical presence of V’ger – were singled out for damnation, with some suggesting they only served to demonstrate how weak the plot was. An apparent lack of character development was cited, despite heavy dialogue. Several critics decried the amount of time characters were seen reacting to information on screens on the bridge, one saying the movie felt like “watching someone else watch television.” In later years the movie attracted negative nicknames including “The Motionless Picture” and “The Motion Sickness” – and, in reference to its similarity to “The Changeling," “Where Nomad Has Gone Before.”

“I think Bob [Wise] and Gene Roddenberry were looking for a Space Odyssey kind of thing, like [Stanley] Kubrick had done,” Nimoy said in 2012, calling The Motion Picture a “beached whale.” He noted that the film had “a cold, cool 'we’re out here in space and it’s kind of quiet and things move very slowly" vibe. "There was a lot of that and a lot of cerebral stuff. There wasn’t enough drama. It just wasn’t a Star Trek movie. We had the Star Trek people, but it didn’t use us as Star Trek characters very well.”

In 2017 Shatner said he regretted the way the tight deadline had meant that Trumbull’s effects appeared unedited, and imagined it would have been a difficult thing for Wise to have lived with. “So the film never got the detailed attention that Wise, who was an editor, a renowned editor himself, would have done,” Shatner explained. “[It] staggered on the screen and would have been much more athletic if it lost several pounds. But we never had the opportunity to do that.” (Wise released a director’s cut in 2001.)

Still, Star Trek was back and it had been enough of a success to persuade Paramount to commission a second movie (also, rumors suggest the wife of a leading Paramount investor liked the show, and told her husband to make more). Blaming Roddenberry for most of the production problems, the studio removed him from control of his creation and hired Harve Bennett, a TV man, to reconnect the franchise to its roots. Now secured as big-name movie stars, the senior cast were able to have more say in the development of their characters. And, despite having a strict and tight budget imposed over it, The Wrath of Khan was to prove once and for all that Star Trek should never have been canceled.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture - Enterprise Scene

The Best Rock Movie From Every Year: 1955-2018

More From Ultimate Classic Rock