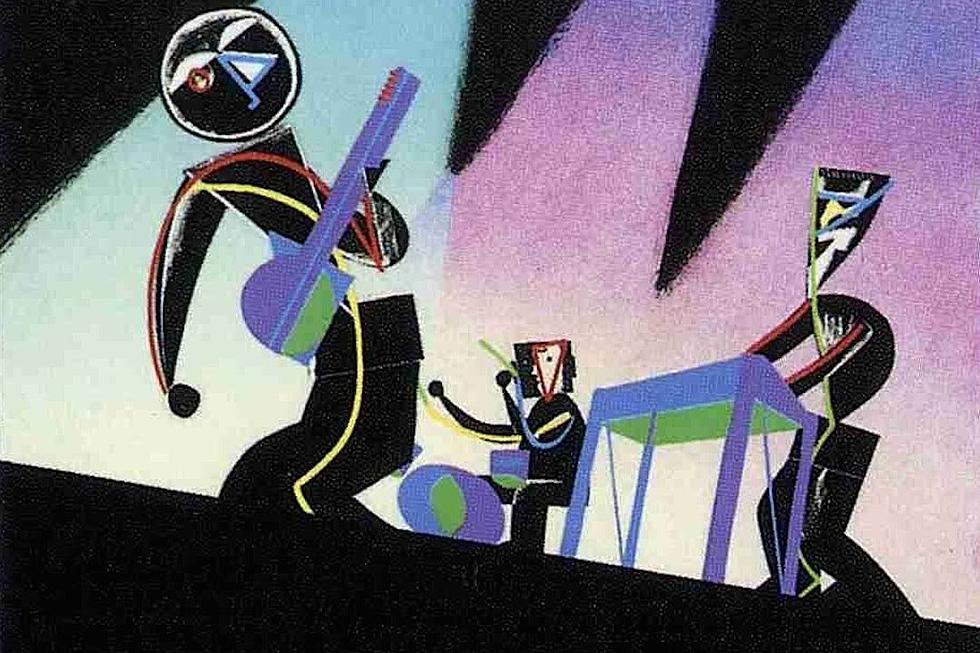

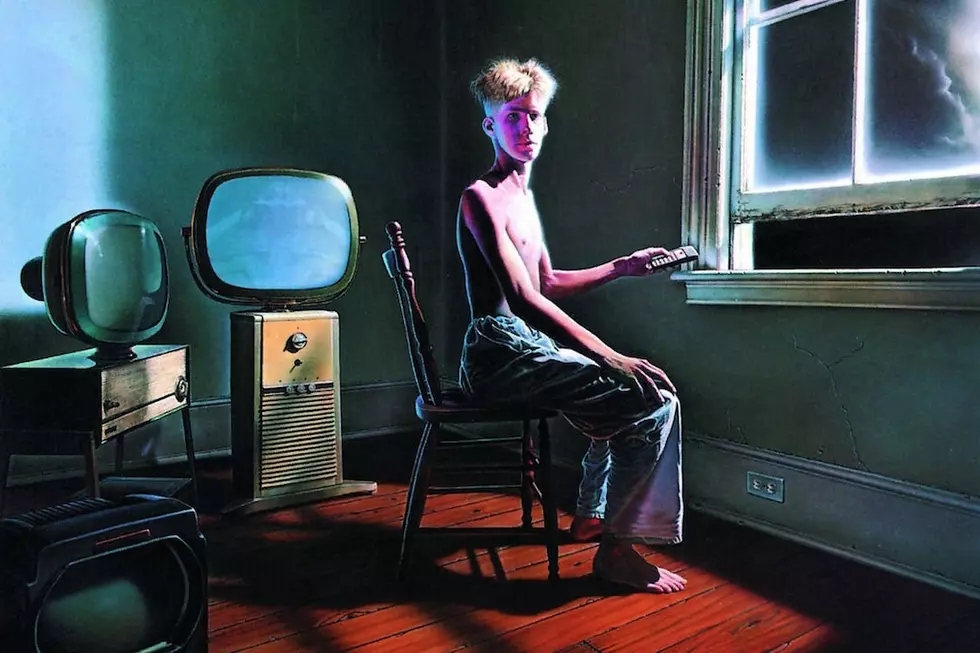

When Rush Upgraded to Neon-Tinted ‘Power Windows’

"So much style without substance," frontman Geddy Lee sings to open "Grand Designs," a sleek prog-pop gem from Rush's 11th LP Power Windows. For hardcore Rush fans who refused to accept anything besides concept albums and tricky time-signatures, Lee might as well have been singing about his own band in the mid-'80s.

But Power Windows, released on Oct. 29. 1985, is the Canadian trio's most underrated album – the point where Rush melded their prog-rock and New Wave personalities.

The prior year's Grace Under Pressure defied the sentiment of its title. Glossy and confused in all the wrong ways, the LP found the band limping deeper into the decade, sounding unsure of themselves.

"We realized with Grace Under Pressure that we were not a techno-pop band," Lee told Guitar World in 1986. "We pretended to be from time to time, and we realized there are some very dramatic differences between us and that kind of music that will never allow us to have that same sound.

"We have a rhythm section that is hyperactive and very alive and most of those techno-pop sounds are very cool, controlled, minimalistic rhythm sections," he continued. "No wonder the snare sounds so great. There's nothing else there. That sound was so seductive, that big hi-fi sound. We realized why a lot of those things weren't part of our music, but we realized we could take some of them and use them. We stopped denying what we were a little bit on this album. Last year we were obsessed with getting new sounds."

To redeem themselves, the band – Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson, drummer-lyricist Neil Peart – recruited producer Peter Collins, crafting songs that emphasized their visceral power along with melodic simplicity.

"Manhattan Project" irritated some fans with its massive synth pads and sparse arrangement, but the focus paid off, helping the track crack the Top 10 on Billboard's rock chart. It's a perfect example of Rush's ability to subvert expectations: The rhythm section is deceptively agile, belying the shiny surfaces. Meanwhile, it's easy to miss the bleakness of Peart's lyrics, meditating on the potential devastation of a nuclear threat, given the breeziness of Lee's lower-register vocal.

Listen to Rush Perform 'The Big Money'

"Normally Neil writes from outside observations, whereas with 'Manhattan Project' he took facts, and put them together as an objective point of view about the power of technology and science, about how we use and have used it, and how it changes where we're going," Lee told Sounds in 1985, also describing the political themes of other Power Windows tracks.

"'Territories' deals with a more global power that we have as people, people on the same planet," Lee added. "I guess in some ways it is dark, but it is optimistic...we don't need to fight over stupid pieces of dirt. The whole gist of 'Territories' is something that he feels very strongly, that we do need to break down the borders, and perhaps we could get along better as people rather than as Americans or Canadians or whatever. In that way we are all political, but as far as rigid politics go..."

There's plenty of instrumental firepower on Windows – see the barking-dog slap-bass of "Big Money" or the crashing 7/8 attack of "Marathon," which climaxes with a 25-piece choir. But Rush were learning how to integrate that muscle with simpler melodic patterns and cleaner production.

"More compact – see if we can do something in five minutes that's as effective as something that takes us 20 minutes to do," Lee told MTV around the LP's release. "[Something] that has stronger melodies, maybe doesn't change its time signature every minute. Maybe we can stay in 4/4 and try to make a song that works. I think we always underestimated the value of that and the difficulty of that. It's not so easy to write a good four, five minute song."

Seven years after their excessive prog-rock masterpiece, Hemispheres, Rush had lightened up. And the songwriting strength of Power Windows proved that "streamlined" wasn't a dirty word.

"[That more bombastic style] wouldn't be satisfying anymore," Lifeson told Sounds. "After we did Hemispheres, we reckoned we'd taken that whole concept thing to its maximum. Anything beyond that would have been really redundant. It was time for a change. It was a nightmare, no days off, long, long hours, losing sight of the end at times. I think that was part of the reason why we thought we'd taken it as far as we could. There was really no point in trying that again."

Top 50 Progressive Rock Albums

Odd Couples: Rush and Aimee Mann

More From Ultimate Classic Rock