Rolling Stones’ ‘Exile on Main St.': A Track-by-Track Guide

The Rolling Stones fled to the south of France in the summer of 1971, after a notably turbulent period.

Cofounder Brian Jones had been found dead in July 1969, only to be replaced by Mick Taylor a couple of days later for a Hyde Park performance in London. Next came devastating violence in December 1969 at the Altamont Speedway in San Francisco, which culminated in the murder of Meredith Hunter.

The band's very own Rolling Stones Records launched in 1971, followed by the exceptional success of Sticky Fingers. They'd been assured that their finances were in order, but the Stones then learned that they owed the British government a small fortune in back taxes.

Exile to France seemed the most sensible option.

Keith Richards had rented the Villa Nellcote, a 16-room mansion nestled on the coast. A makeshift studio was set up in the basement with the band's mobile recording unit, which by then had already been used during sessions for Sticky Fingers, as well as Led Zeppelin III and IV, and the Who's Who's Next. Work began on the next Rolling Stones record with the assistance of producer Jimmy Miller, engineers Glyn and Andy Johns and additional musicians including pianists Nicky Hopkins, Billy Preston and Ian Stewart, saxophonist Bobby Keys and horn player Jim Price, among others.

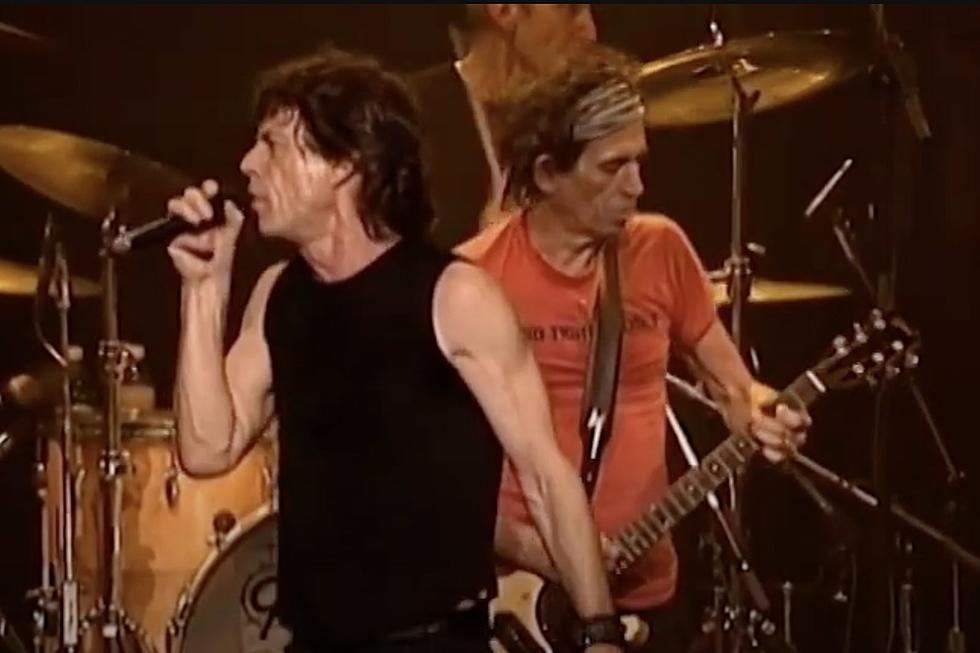

The tranquility of the French Riviera, however, stood in stark contrast to the work being done inside the walls of Nellcote. Richards reached what many considered the height of his hard drug habit, various members of the band were sometimes not present to record their parts and the differences between the working styles of Richards and Mick Jagger were exacerbated. Jagger was often keen to keep the process moving, while Richards was content to take things slower in a drug-fueled modus operandi that Charlie Watts once referred to as "Keith time."

"Mick needs to know what he's going to do tomorrow," Richards said in Stones in Exile, a 2010 documentary about the making of the album. "Me, I'm just happy to wake up and see who's hanging around. Mick's rock; I'm roll."

The Rolling Stones eventually escaped this disorderly environment to complete things in Los Angeles, emerging with their first double LP. Exile on Main St. was released in May 1972, just before the band set off on an American Tour — their first appearances in the U.S. since Altamont.

Exile on Main St. would be hailed as one of the Rolling Stones' greatest albums, landing at the top of the charts across the globe. As this track-by-track guide illustrates, the LP also contains some of the roughest rock 'n' roll of their career.

"Rocks Off"

In many ways, "Rocks Off" sets the scene for what lies ahead on Exile. In his garbled tone, Jagger sings lyrics that paint a pretty accurate picture of what Villa Nellcote was like, powered by drugs to the point where pain couldn't be felt any longer and even the sunshine was boring: "I'm zipping through the days at lightning speed / Plug in, flush out and fire the fuckin' feed." A middle-eight section suddenly drops into a psychedelic haze with stretched guitar chords and Jagger's voice distorted, just before the song ramps back up. The overall feel of the song displays the same haphazard complexion: It was difficult to keep the guitars used on Exile in tune in the damp, hot villa basement.

"Rip This Joint"

There's a near-frantic pace to "Rip This Joint," a rockabilly-style song that's one of the fastest in the Stones catalog. Jagger's whirlwind speed is only broken by a pair of saxophone solos. Several cultural references are scattered throughout, including "Dick and Pat in ole D.C.," an allusion to then-President Richard Nixon and his wife. Also mentioned is the "Butter Queen," a well-known rock groupie from Dallas. Barbara Cope never revealed how she got the nickname before her death in 2018. "Those who know, know," she once said, "and those who don't, wish they did."

"Shake Your Hips"

Never ones to stray too far from their blues influences, the Rolling Stones next offer an update on Slim Harpo's "Shake Your Hips." The oft-covered Harpo's most successful recordings included 1957's "I'm a King Bee," 1961's "Rainin' in My Heart" and 1966's "Baby Scratch My Back" the last of which would reach No. 1 on the Billboard R&B chart. "Shake Your Hips," didn't fare as well on the charts, but was still memorable for being the lead single from his 1966 album, Baby Scratch My Back. Dozens of musicians recorded versions of Harpo's songs over the years, including Yardbirds, Otis Redding, George Thorogood and the Destroyers, Them, the Kinks, Johnny Winter and more.

"Casino Boogie"

The lyrics to "Casino Boogie" are not supposed to make sense. That's because the band scribbled them at random, then plucked them out one by one. "That song was done in cut-ups," Jagger told Uncut in 2010. "It's in the style of William Burroughs, and so on. 'Million-dollar sad' doesn't mean anything. We did it [during final recording sessions] in L.A. in the studio. We just wrote phrases on bits of paper and cut them up – the Burroughs style – and then you throw them into a hat, pick them out and assemble them into verses. We did it for one number, but it worked. We probably did it 'cos we couldn't think of anything to write." "Casino Boogie" has never been performed live.

"Tumbling Dice"

The first recording of "Tumbling Dice" — a song whose origins lay in an earlier tune called "Good Time Women" — featured Taylor on bass (Bill Wyman was inexplicably absent from the session) and Jagger on rhythm guitar. The lyrics came from Jagger's conversations with the villa's housekeeper about gambling. "She liked to play dice and I really didn’t know much about it," Jagger later remembered. "But I got it off of her and managed to make a song out of that." Like a handful of other songs from Exile on Main St., "Tumbling Dice" features Richards' now-famous five-string open G tuning – affectionately known as the "Keef-chord."

"Sweet Virginia"

Things get slowed down a bit at the top of side two of Exile with "Sweet Virginia," a laid-back country-style shuffle thought to be influenced by Gram Parsons, who was a regular visitor at Villa Nellcote. “I absorbed so much from Gram," Richards wrote in his autobiography, Life. He specifically mentions "that Bakersfield way of turning melodies and also lyrics, different from the sweetness of Nashville; the tradition of Merle Haggard and Buck Owens, the blue-collar lyrics from the immigrant world of the farms and oil wells of California – at least times where it had its origins in the '50s and '60s. That country influence came through in the Stones." This is one of five tracks from Exile on Main St. that triggered a lawsuit from former manager Allen Klein for breach of settlement. Klein argued that the songs had been written while they were still technically under contract with his company, ABKCO. Klein won the suit and ABKCO acquired publishing rights to "Sweet Virginia," "Loving Cup," "All Down the Line," "Shine a Light" and "Stop Breaking Down."

"Torn and Frayed"

Continuing in the flavor of Parsons, "Torn and Frayed" sees Taylor moving to bass. Al Perkins, a friend and frequent collaborator of Parsons, plays pedal-steel guitar. This song was performed on the Stones' 1972 tour of America but then did not appear on set lists for three decades until it resurfaced during the fall leg of their 2002 Licks Tour.

"Sweet Black Angel"

This track began life as an "island-lilt sort of thing," Richards later remembered. Then Jagger started writing the lyrics, and everything took a political turn. “After a while, the words ‘Sweet Black Angel’ crept into it," Richards said, "and I realized Mick was writing about Angela Davis, the famous activist who was under arrest at the time.” Davis had been charged with kidnapping and first-degree murder after originally purchasing guns used in a deadly courtroom shooting. She became the third woman ever to be placed on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted Fugitive List after going on the lam for close to two months. Jagger saw a wanted poster of Davis in Paris, inspiring the song. “We had never met her, but we admired her from afar,” Richards added. Davis was acquitted not long after fans finally had a chance to hear Jagger singing, "Well de gal in danger, de gal in chains / But she keep on pushin' / Would you do the same?"

"Loving Cup"

"Loving Cup," another of the songs involved in Klein's lawsuit, was first worked on during sessions for Let It Bleed. The band performed it nearly two full years before Exile on Main St. was released, with Jagger introducing the song as "Gimme a Little Drink" at their July 5, 1969, concert at Hyde Park. Producer Jimmy Miller plays maracas on the track.

"Happy"

"Happy" was notable for Richards' placement on lead vocal, and for coming together very quickly. "We did that in an afternoon, in only four hours, cut and done," Richards wrote in Life. "At noon, it had never existed. At four o'clock, it was on tape." The track materialized so swiftly that Richards and Jagger are the only members of the Rolling Stones who appear. Richards cut the bass part himself, while Miller played drums. "It just came tripping off the tongue, then and there," Richards added. "When you're writing this shit, you've got to put your face in front of the microphone, spit it out. Something will come." It's the only Stones song with Richards singing lead that charted on the Billboard Hot 100.

"Turd on the Run"

Very little is known about "Turd on the Run," which makes an appearance on the second disc of Exile on Main St. Bassist on the track was Bill Plummer, a session musician who also recorded with Miles Davis, Nancy Wilson, Tony Bennett, Willie Nelson and Ry Cooder, among others. Part of the song's apparent aimlessness might have been the result of the Stones' decision to move to L.A. as sessions continued into the winter of 1971: "It was like, 'Anything goes. We need to get this done,'" Jagger said in Stones in Exile. "Turd on the Run" has never been performed live.

"Ventilator Blues"

One of just two Rolling Stones songs that Taylor was given co-writing credit on, "Ventilator Blues" has only been played live once. The late Watts chalked that up to difficulty in recreating the original. "Something will not be quite right: Either Keith will play it a bit differently or I’ll do it wrong," Watts said in According to the Rolling Stones. "It’s a fabulous number, but a bit of a tricky one. [Saxophonist] Bobby Keys wrote the rhythm part, which is the clever part of the song. Bobby said, ‘Why don’t you do this?’ and I said, ‘I can’t play that,’ so Bobby stood next to me clapping the thing and I just followed his timing. In the world of Take Five, it’s nothing, but it threw me completely and Bobby just stood there and clapped while we were doing the track – and we've never quite got it together as well as that." Taylor's other co-writing credit, "Criss Cross," went unreleased until 2020's deluxe edition of Goats Head Soup.

"I Just Want to See His Face"

"I Just Want to See His Face" was a track that started as a jam session and reportedly features Bobby Whitlock of Derek and the Dominos. "[Jagger] asked me to play something with a gospel feel as he sang along," Whitlock later said in a Facebook post. "Charlie jumped in and Mick Taylor started playing the bass. That's exactly how it went down. Keith Richards was nowhere near the studio, even though he was credited as a writer and piano player on it." The song is a personal favorite of Tom Waits, who took an immediate liking to Jagger's high falsetto. "When he sings like a girl, I go crazy," Waits told The Guardian in 2005. "I said, 'I've got to learn how to do that.'" Whitlock was never credited on "I Just Want to See His Face," and the Stones have not confirmed his presence.

"Let It Loose"

"Let It Loose" features Dr. John singing backing vocals, and culled some lyrics from the American folk standard "Man of Constant Sorrow": "Maybe your friends think I'm just a stranger / Some face I'll never see no more." Unfortunately, neither Jagger nor Richards can remember how the song came about. “I think Keith wrote that, actually," Jagger told Uncut in 2010. "That’s a very weird, difficult song. I had a whole other set of lyrics to it, but they got lost by the wayside. I don't think that song has any semblance of meaning. It’s one of those rambling songs. I didn’t really understand what it was about, after the event.” Richards concurred, adding: “I would never take Mick’s recollection of anything seriously.”

"All Down the Line"

"All Down the Line" was the first song they finished for the album, but there was really only one way for the Stones to determine if they had a good single: give it to the radio. They did exactly that, handing over the still semi-unfinished song to a Los Angeles station to be played on air. The Rolling Stones then drove around town listening to it. "It was surreal,” engineer Andy Johns told Rolling Stone. “Up and down Sunset Strip at nine on a Saturday night – the Strip was jumpin’ and I’m in the car with those guys listening to my mixes." "All Down the Line" appeared as the B-side to "Happy."

"Stop Breaking Down"

The second blues cover from Exile on Main St., Robert Johnson's "Stop Breaking Down," arrives late in the album. They'd long been fans. "When I first heard it, I said to Brian, 'Who's that?' 'Robert Johnson,' he said," Richards recalled in the liner notes to the Johnson box set Complete Recordings. "'Yeah, but who's the other guy playing with him?' Because I was hearing two guitars, and it took me a long time to realize he was actually doing it all by himself." The only problem was the album initially failed to credit Johnson, listing the track as part of the public domain – just as they had with a cover of Johnson's "Love in Vain" from Let It Bleed. Johnson's estate filed a lawsuit arguing that the songs were still under copyright protection. The Stones' early-era publishing company was found in violation, and Johnson's name was added to subsequent reissues. The Stones have performed "Stop Breaking Down" only once in concert, pairing up with Robert Cray for a version included on Voodoo Lounge Live.

"Shine a Light"

The original 1968-era lyrics for "Shine a Light," then titled "Get a Line on You," focused on Brian Jones and his increasing issues with drug addiction. Three years after Jones' death, the song was reworked for the final version: "Saw you stretched out in room 10-o-nine, with a smile on your face and a tear right in your eye / Oh, couldn't seem to get a line on you." Billy Preston played keys on the track, while Miller returned to the drums. “Jimmy Miller was a damn good drummer,” Richards wrote in Life. “He understood groove."

"Soul Survivor"

"Soul Survivor" might be considered something of a deep cut, but it closes Exile on Main St. with just the right amount of blues-infused energy. A different version of the track, with Richards subbing on lead vocals, was one of the more intriguing finds on a 2010 reissue. It once again spoke to the off-handed way they created an album that now ranks among rock's very best. "I recall making it all," Jagger told Rolling Stone. "It was just where and when and with who was another matter. Who’s playing what? It wasn’t always put down who’s playing guitar and who’s playing keyboard and that sort of thing. There are still a few mysteries."

Top 40 Blues Rock Albums

See Keith Richards Through the Years

More From Ultimate Classic Rock