R.E.M.’s ‘Chronic Town’ Reissue Sparks Memories for Peter Buck

R.E.M. was still working to find their way when Chronic Town arrived in 1982. But the band was already thinking more pragmatically than many of their peers.

As guitarist Peter Buck says in the liner notes to the 2022 reissue for the EP, they knew they didn't want to make a full-length studio project – even if they had the songs. R.E.M. was wary of releasing an album that nobody would hear. Instead, the focus was on building to that moment by creating a strong foundation for when the time felt right.

That said, even this smaller group of songs felt like "an entity that had to be kept intact," as Chronic Town producer Mitch Easter writes in his essay for the reissue. He called "Radio Free Europe," the independent single which arrived prior to the EP, a "signpost." Chronic Town was the "atlas" that followed.

While none of them knew it at the time, this atlas would help chart the many travels and experiences that followed for R.E.M.

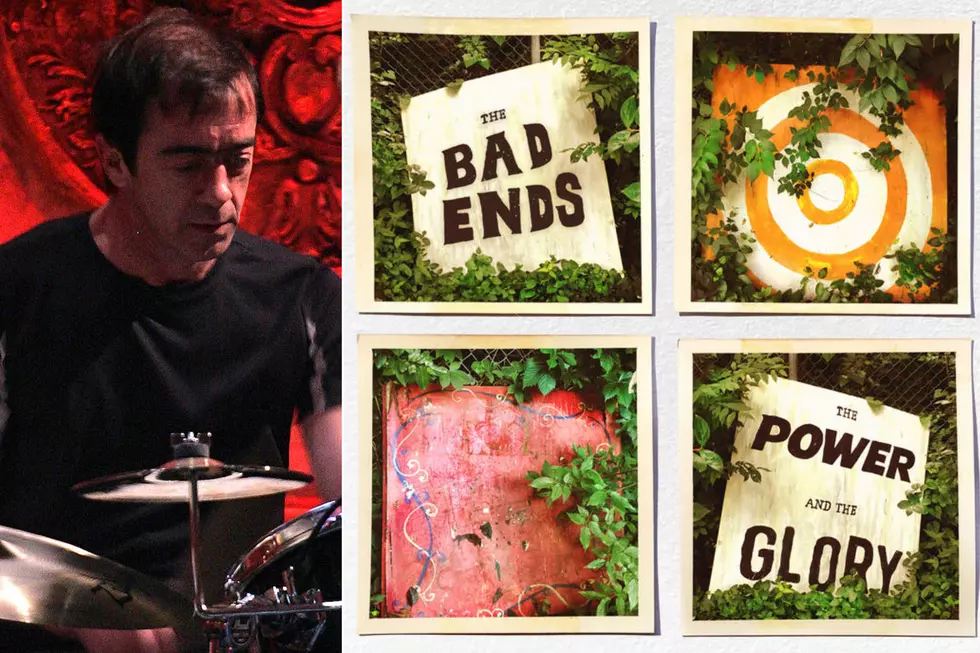

Buck and his former R.E.M. bandmate Mike Mills recently had the chance to record with Easter again. The famed producer helped oversee sessions for the next album from the Baseball Project, a sports-themed collective featuring Steve Wynn of the Dream Syndicate as well as Scott McCaughey and Linda Pitmon.

During a conversation with UCR, Buck shared insights on the Baseball Project sessions, the experience of reuniting with Easter, and his own Chronic Town memories.

Listen to 'Wolves, Lower' by R.E.M.

It seems pretty special that you got to work with Mitch again with the Baseball Project.

It was just unbelievable. My daughter was there. We did a little road trip and she came in. You know, I’ve known Mike since 1979. I’ve known Mitch since 1980. I’ve known Steve and Scott since like ‘83. Linda is the new gal on the block and I’ve known her since ‘96. It’s like, this is just a lifetime of people that have been together, in this room. It was pretty moving and really cool. My daughter was kind of fascinated by the whole thing that you have really good friends that you’ve had for over 40 years.

When I saw Steve play a show in 2021, he mentioned to the audience that you had just emailed him a song overnight prior to that day. It seems like things are always pretty fluid collaboratively.

I think I’ve only written one Baseball Project song before this record. Because it’s a different – you know, they’re story songs, so you’ve got to leave a lot of space for the story to unfold. I don’t usually write songs like that but Steve came to me and said, “We’re making this record with Mitch, why don’t you send me something that sounds like R.E.M. in 1983.” I went, “Okay, that’s easy.” You know, E Minor, D, think of some chords. I sent it to him and it turned out great. It’s called “Journeyman” and it’s on the next record. During that time, Scott just started pulling out a bunch of demos that I’d done at his house and said, “Hey, I found this song of yours. Do you mind if I write to it?” I’m like, “No, go ahead.” So I co-wrote, I think, like four of the songs on the record.

Some people have a difficult time when they're given a prompt of what to play and the style, but you seem pretty flexible with that.

Yeah, you know, my recording and playing life, there’s basically two elements. There’s the self-motivated, “This is what I want to accomplish” part and then there’s the “I’m working with someone else. I don’t mind if you tell me what you want me to do.” You know, if you want me to play on your record, if you tell me exactly what you want, I can do that. And if you don’t, then I can give you one from column A and two from column B. I’ll give you the Peter Buck arpeggio chime-y 12-string type thing. And then maybe I’ll make noise or a really weird four-note guitar solo or something. But when I’m in the studio, if someone tells me exactly what they want, I don’t mind. As long as I can do it, it’s like, “Yeah, it’s your record, I’m cool with that.”

Mitch wrote a great essay for the new Chronic Town reissue and it seems like he spoke to each of you as he was writing it. What sort of memories did that bring out for you?

You know, I only ever think about stuff like that if I’m with someone who asked me the question. I have friends who are a little younger than me who grew up listening to the music and every now and again, someone will go, “Well, what was doing that like?” – and I’ll have to think back. I don’t really think about it that much. I have really strong memories [though] of going to Mitch’s place to do Chronic Town. I think in total it was three days that we spent on it, maybe four. It was definitely an attempt to try to figure out, “What do we want to do in the studio? How do you utilize the studio?” Mitch was the ideal guy to guide us, because he knew. I mean, I was like, “What’s a tape loop?” He’d make a tape loop and show me.

You go through a lot of things in that embryonic era that you're probably never going to go through again.

Yeah, you know, I read pretty much every rock biography or autobiography down the line – and basically, the way up and the way down are more interesting. The being successful [part of it] is really boring – it just is. “So then we sold another million records and got some awards.” Who cares! But you know, the starting is great. Honestly, the way people handle the end is very instructive. I’m proud of the way all four of us in the band have [handled that]. We went on to other things. You know, nobody’s sitting around the house taking heroin and depressed that they’re not famous anymore.

Watch R.E.M. Perform 'Carnival of Sorts (Box Cars)' at Olympia

I know this came a bit before "the end," but [longtime band advisor] Bertis [Downs] posted about the Live at the Olympia album recently. I remember listening to bootlegs of all five nights, and you later lovingly called the experience "an experiment in terror." To me, it seems like playing those shows bottled a lot of good moments for R.E.M. as a band.

It’s the kind of thing that I would have liked to have done more often, but it’s just hard to get the whole machine to move that way. Let’s go someplace and do a whole bunch of shows in front of people doing new songs and see what happens. But we only had like 10 new songs so it was like, “Yeah, we’re not going to play 45 minutes. We can’t do that.” I was doing a tour with someone and asking people, “Well, what do you want us to do when we’re doing these five shows? We’re only going to be doing nine or 10 or 11 new songs. What should the other stuff be?” Everyone said the same thing, “Don’t play the hits.” Do not go out and play 'Losing My Religion' and [stuff like that]." So it’s like, “Okay, what should we do?”

We just decided that we were going to try to do different stuff, pretty much every night – which made it way harder, because some of those songs, we hadn’t played since the ‘80s. [Late-period drummer] Bill [Rieflin] had never played them. Maybe Scott hadn’t either, for that matter – but it was great. We would just play the record and learn them. It was amazing how fast it came back. You know, some of those songs, we had played once that afternoon, but it was cool, because it kind of reminded me, “Okay, this is how you do it. These are what the old songs sound like. This is what the new songs sound like.” You’re not super-prepared. [Frontman] Michael [Stipe] was up there taking notes on his notebook and I guess [also] on his computer. You know, I’d do that kind of thing every year if the band was still going, if it was up to me.

You worked with Robert Fripp on what became known as the Slow Music project. How much did you come to know Robert as a result of doing that?

I’m a fan of his music, but I’d never met him until basically we rehearsed for those things. It’s hard to rehearse improv, but we spent two days in the studio just doing improv. He’s a really charming, really smart and funny guy. He’s like a long line of kind of great English eccentrics. So yeah, I don’t know him personally. Like, he hasn’t shown me his heart or whatever, but just working together and having a couple of dinners and hanging out, I really got to see the other side of that heaviness of King Crimson. He’s kind of a light-hearted person. It wasn’t until those things with [Fripp's wife] Toyah [Wilson] that they started doing, where people could see that. But yeah, he’s kind of goofy, as well as being very intellectual and well-read and smart.

What did you take away from the experience?

I played sitting down and it was like, “Fuck, this is harder than anything I’ve ever done.” You know, a couple of hours of absolute focus. You don’t know what you’re going to play next. I mean, I couldn’t have done it if it was really fast. But at a certain point, all you’re doing is deciding what you want to add to the conversation. I think it made me rethink a little bit of my idea of how to play and how not to play, and leaving space in things. I’ve always been conscious of that, but I kind of came away going, “Yeah, I don’t have to play every second of every song." Not that I have done that – but it just kind of made everything I do feel a little more open.

The Most Awesome Live Album From Every Rock Legend

More From Ultimate Classic Rock