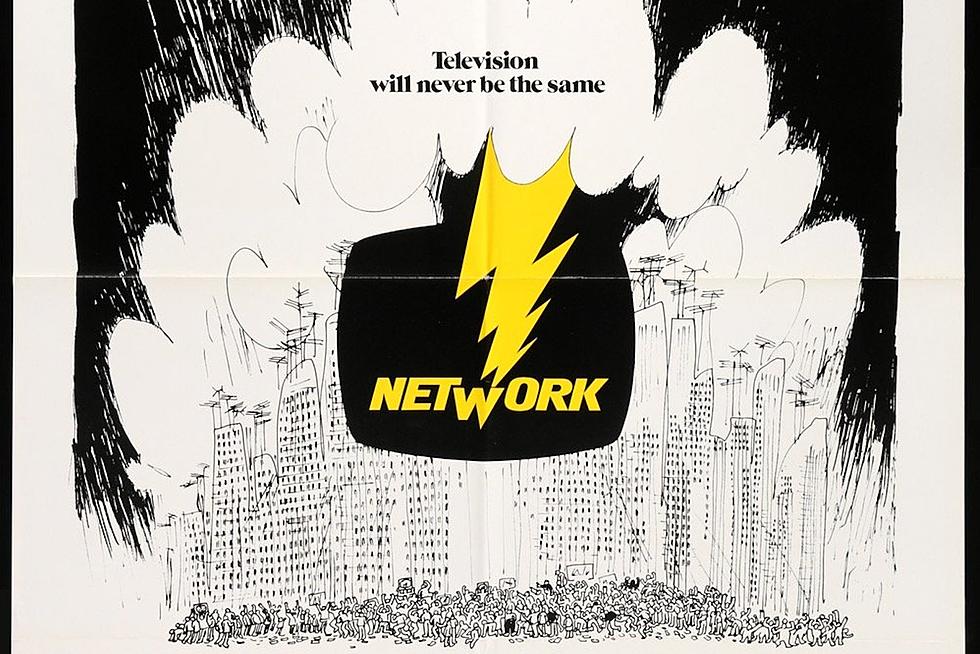

How ‘Network’ Went From Cinematic Satire to Prophetic Reality

There are few lines in the history of film or television (let alone television portrayed on film) that had the cultural impact of, "I'm mad as hell and I'm not gonna take it anymore."

The line, from 1976's Network delivered by Howard Beale (Peter Finch), a news anchor and "mad prophet of the airwaves" having a psychotic break, not only got audiences in the film yelling out their windows, but captured the anger and imagination of Americans who repeated it for decades.

Recitations of the iconic line aren't just in songs and movies. On the occasion of Network getting its first airing on a network, (CBS in 1978), screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky told the Washington Post, "I get letters about it happening all the time — after Proposition 13, or during the New York blackout. People were yelling, 'I'm mad as hell, and I'm not going to take it any more.'"

In the 45 years since its release, it's clear that both the populace and TV news have only gotten madder. The dark comedy was written as a satire that, at the time, annoyed legions of TV news anchors and personalities. A few decades later, what couldn't be fully appreciated was how prescient the screenplay was about conglomerates, capitalism and news as infotainment.

Chayefsky and director Sidney Lumet had a background in the so-called Golden Era of TV: the 1950s when most television was live and an era from which we now lionize the news and its presenters, including Edward R. Murrow and Walter Cronkite, as bastions of fairness and morality. By the '70s, television turned from a predominantly live and informative medium into a wasteland of game shows and mindless procedurals. And news programs, rather than taking the government to task for the drawn-out wars and scandals of the era, seemed to pivot into news magazines like 20/20 and 60 Minutes, aimed at enthralling and sometimes titillating the public. In short, it had become mindless content for consumption.

We see that mindlessness in the nightly news by UBS, the fictional network in the film, and in the ambitious head of programming who puts that together, Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway), featuring no actual news but rather Beale's rantings, a soothsayer and a segment called "vox populi," which, not surprisingly, is said to develop its own following.

Watch the Trailer for 'Network'

While it feels a bit wild in these times to hear about one news program on broadcast television reaching 30 million viewers ages 18-34, the advertiser sweet spot, the accuracy of Chayefsky's rant decades later is even wilder. Placed in Beal's mouth, he goes on about corporate conglomerates controlling what we see and influencing how we act, which only increased in the real world with loosening regulations under Presidents Reagan and Clinton. At some point in history, Network stopped being satire and transitioned to political commentary.

In a 2011 New York Times article on Chayefsky, then news satirist Stephen Colbert said, "Howard Beale is a precursor of people who are telling you how you feel. Not just the nighttime people that I'm sort of a parody of, not just the opinion-making people, but even what is left of straight news."

The film's most harrowing scene comes when Beale is summoned to the corporate offices of the conglomerate who own the network to meet with Arthur Jensen (Ned Beatty) and hear the infamous pitch speech in which Jensen becomes both the voice of God and reason that Beale feeds back to the people. Unfortunately, Jensen's nihilistic message that individuals are worth nothing and we live in a world not of nations, but corporations, is too depressing for audiences to tune in to. Jensen's insistence that Beale stays on the air puts network head Frank Hackett (Robert Duvall) between a rock and a hard place. And that's how the viewer finds themselves in a room with the leaders of various departments at the network as they plot the assassination of Howard Beale for the reason of low ratings. All this despite the warnings of his best friend and the former head of news programming, Max Schumacher (William Holden).

Network would win numerous awards, including four Oscars: Best Screenplay, Best Actor for Finch and Actress for Dunaway. And Beatrice Straight, for her portrayal of Schumacher's put-upon and cheated on wife, Louise, won the Best Supporting Actor statue that to date was awarded to the character with the least amount of screen time in Academy history. While Lumet didn't get an Oscar, he did earn a Best Director Golden Globe.

Finch wouldn't be on stage to accept his award. The actor passed away during the press tour for the film from a massive heart attack in a hotel lobby. Ironically, along with Lumet, he was on his way to make an appearance on ABC's Good Morning America to promote his movie to the masses.

40 Essential Movies That Turn 40 in 2021

More From Ultimate Classic Rock