50 Years Ago: Hiding Away Helps Led Zeppelin to Greatness on ‘IV’

The best Led Zeppelin studio album is one that was, quite literally, the most lived in.

Sessions for IV were recorded in the Rolling Stones' mobile studio outside of a largely derelict East Hampshire-based Victorian, in what Jimmy Page later described as a commitment to "eating and sleeping music together." Hidden away at Headley Grange, the group fashioned their most ambitious LP ever.

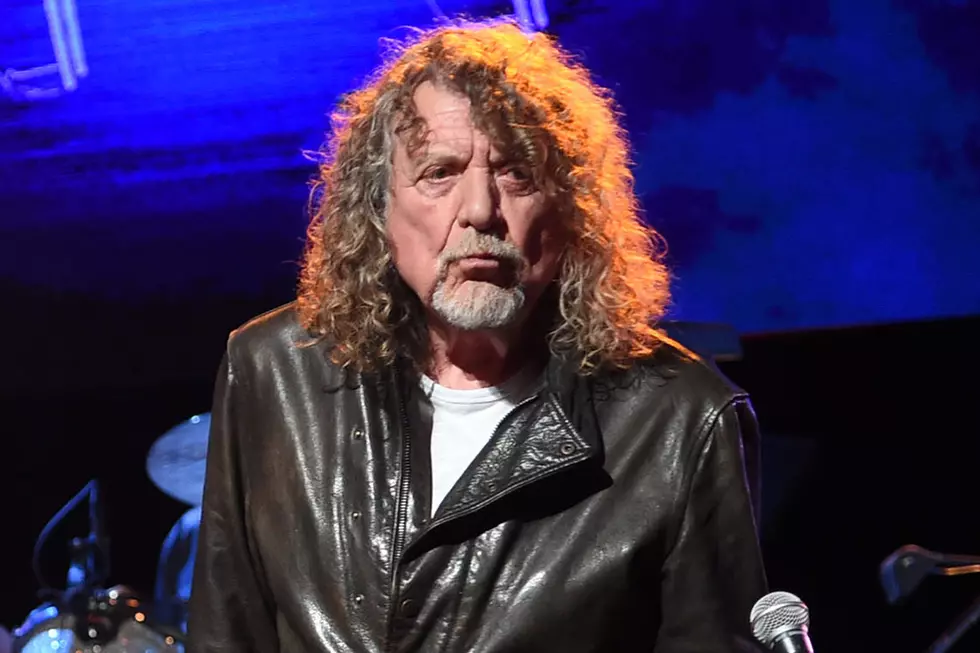

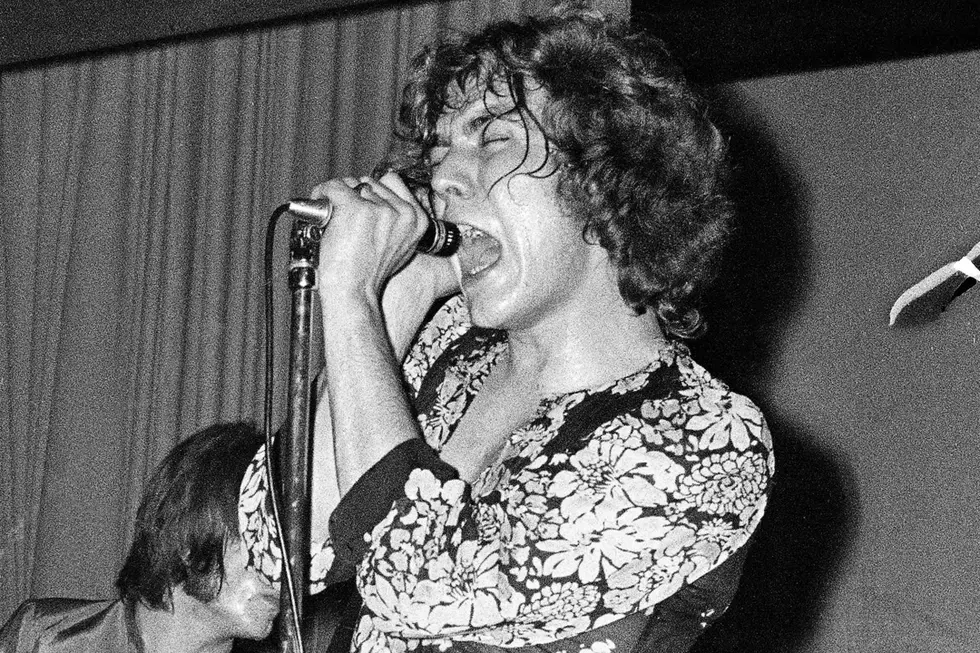

An early template was established when they created a portion of Led Zeppelin III at Robert Plant's Welsh holiday cottage Bron-Yr-Aur. The duo learned that leaving the world behind helped spark their burgeoning imaginations. Led Zeppelin's next album would dive headlong into that isolation, as Page and Plant were joined by John Paul Jones and John Bonham in an enveloping creative space.

"With the fourth album," Page told the Quietus in 2014, "the fact that it was recorded under conditions where we were living in a house, eating, sleeping and recording there with the benefit of a mobile recording studio that was sitting out in the drive, it really gave us the opportunity to give 100 percent commitment to the record."

Jones and Page worked on the music, before they presented largely constructed demos to Bonham. "The whole time, Robert was listening and writing," Page told Mojo in 2021. "Then he started singing and had most of the lyrics written. … It was an inspired time for everybody."

That doesn't mean the winter of 1970-71 was easy inside a poorly heated 18th-century manor. Jones, in fact, bitterly complained about the living conditions. But the space ended up becoming part of the process: "When the Levee Breaks" took advantage of its natural acoustics, while "Black Dog" was named after a neighborhood stray.

"Headley Grange was cold, damp, dirty, smelly," Jones told Mojo. "I remember walking into my room and thinking, 'Oh, really?' I had to steal someone's electric fire." To Page, that wasn't just part of the charm; it was the entire point.

"We were there to work," he responded. "Headley was a bit austere, but there was no 'Let's get stoned or go to the pub and get pissed.' That wasn't our raison d'etre. It was 'eat, sleep, work.' But at the same time, I wasn't walking around with jackboots and a whip."

Listen to Led Zeppelin's 'Stairway to Heaven'

Ultimately, IV brought balance to what had been a whipsawing musical journey: Led Zeppelin's debut album was dark and stormy, while II explored heavier sounds – then III explored lighter ones. They'd hadn't moved past what Plant once described as this "very animal thing, a hellishly powerful thing," so much as used it as launching pad. Together but also alone, form was finally meeting function.

"Most of the mood for the fourth album was brought about in settings we had not been used to," Plant later remembered. "We were living in this falling-down mansion in the country. The mood was incredible."

Time away also gave Page an opportunity to keep a flickering flame of resentment alight. The record was released without a title or any identifying information about the band, meaning dismissive critics would have to figure out what was inside on their own. "After all we had accomplished, the press was still calling us a hype," said Page, who also refused interview requests for more than a year. "So, that is why the fourth album is untitled."

Fans seized upon their own names, and IV became the most widely used. Asked what he called it, Plant told Rolling Stone "just 'the fourth album.' That's it." Later, he admitted that he had no idea how others should refer to it. The album has since also been called Untitled, Zoso and Four Symbols, after the four unpronounceable runes chosen to represent each member of the group on the LP's cover.

In a reflection of their contributions to IV, each symbol was distinct yet obviously related. "The fourth album showcases perfectly everything to do with the band, whether it's the individual performances or how it works collectively, the production and everything to do with it," Page told the Quietus. "It's a really strong time capsule; that's what it is and so different from the albums that came before."

Surrounded by so much history, it's perhaps unsurprising that a song like "Black Dog" boasts ties to a pair of blues greats: Jones thought of the riff for "Black Dog" while listening to Muddy Waters' Electric Mud; Bonham's unsettled rhythm structure on the same track owes a debt to Fleetwood Mac's Peter Green-era gem "Oh Well."

More often, however, they were making things that had never been made – and doing so at a furious rate: Three songs ("Boogie With Stu," "Down by the Seaside" and "Night Flight") from these sessions were left on the cutting-room floor until 1975's Physical Graffiti.

Working where they lived sometimes led to endless retakes, since there was nowhere else to be. But IV was better for it, as deft tinkering vastly improved tunes like "Black Dog" (Page's solo was meticulously pieced together from multiple tries), "When the Levee Breaks" (frustrations with earlier versions led to placing the drums in the Minstrel's Gallery) and, of course, on "Stairway to Heaven."

Every one was said to have considered their first take to be definitive. Everyone, that is, except Page. "Bonham is fuming at this point," recording assistant Richard Digby Smith told Rolling Stone in 2016, so on the next try "he's beating the crap out of his drums."

That second pass through "Stairway to Heaven" became the master. They still weren't done, however, as Page's solo also took more than one attempt.

Listen to Led Zeppelin's 'When the Levee Breaks'

The results, Page later enthused, "crystallized the essence of the band" – but "Stairway to Heaven," despite its herculean fame, isn't the sum total of IV. Led Zeppelin explores dreamy folk and Tolkien promise on "The Battle of Evermore" and "Going to California," but with everything from a flinty jam ("Rock and Roll") to a dive to the bottom of bayou blues ("When the Levee Breaks") found on either side.

"You've got these extremes of music there," Page told the Quietus. "We wanted to concentrate all our energies and the work ethic and the ethos by going there to make music that was so strong and intoxicating to each and every one of us. That's the key to the fourth album: It was residential."

The legend of Headley Grange only grew when Led Zeppelin left and IV nearly derailed. Page took the tapes to complete a final mix at Los Angeles' Sunset Sound, where he and engineer Andy Jones were impressed with the equipment. But then the album came off completely different after they departed.

"While we were mixing, everything sounded huge and the low end sounded especially massive," Page told Guitar World in 2015. "But when we returned to England and played our work back, the sound was nothing like what we had heard in Los Angeles. It was deflated – a pale echo of what we'd heard in L.A."

Page had to start over, scrapping everything he and Johns had done, save for "When the Levee Breaks." Their hard work paid off, as Led Zeppelin IV entered the U.K. chart at No. 10 before rising to the top a week later.

The album didn't hit No. 1 on the Billboard chart, getting stuck behind Sly & the Family Stone, and Carole King. But IV became the most consistent seller in Led Zeppelin's storied catalog, eventually going 23-times platinum in the U.S.

Sensing that something important had happened at Headley Grange, Led Zeppelin returned while recording their next two albums, 1973's Houses of the Holy and Physical Graffiti. That's part of IV's legacy, too.

"It's like there was a magical current running through that place and that record," Page told Mojo. "Like it was meant to be."

Led Zeppelin Albums Ranked

Why Led Zeppelin Won’t Reunite Again

More From Ultimate Classic Rock