50 Years Ago: John Lennon Versus the Dirty Squad in Court

These days, Bag One may be a shopping app, a game show or maybe a space ship in a Star Wars movie. But back in 1970, it was the title of an art exhibition that landed the work of John Lennon in court.

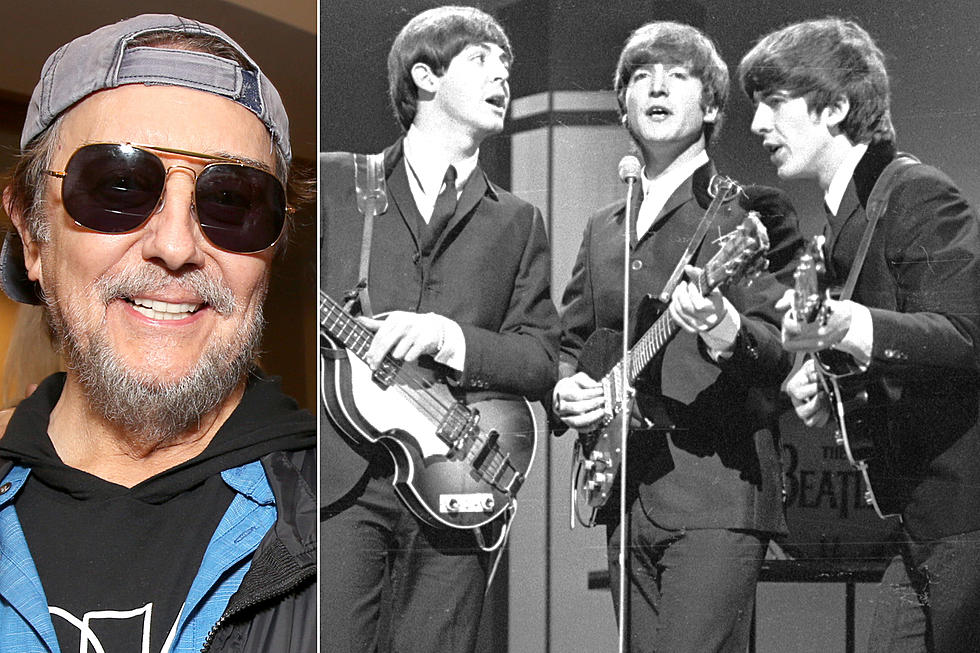

The Beatles were already over, even though the news wasn’t public yet. As perhaps the highest-profile member of the group, Lennon wanted to take the opportunity to explore forms of art beyond music. As a result, he created a series of lithographs inspired by the honeymoon he shared with Yoko Ono around a year earlier.

The problem was his graphics were graphic.

The series depicted moments of oral sex and masturbation that appeared to be part reality, part fantasy. Which, it could be argued, is one of the things art is for – particularly in the case of Lennon, whose fans were desperate for any inkling of his thought process to better understand his other works.

But Lennon's lithography wasn't all that great in the eyes of most viewers. Even Eugene Schuster - director of the London Art Gallery, which staged the Bag One exhibition - later admitted that “some were bad art, some mediocre and some showed good draughtsmanship.”

That, however, was not the point. The point was that an establishment, still reeling from what had been done to them during the ‘60s by a rebellious younger generation, saw an opportunity to lash back. The lashing was attempted by the Obscene Publications Squad of Scotland Yard, commonly known as “the Dirty Squad.” Headed by Detective Inspector Fed Luff, the team raided the gallery almost as soon as the exhibition opened.

Even though more than 50 images were on display – for sale at £40 each, or £550 for the full set, presented in a custom white handbag – only a handful were confiscated by the cops on Jan. 17. Meanwhile, there was just enough time on that January day to make sure a couple of witnesses of respectable social standing were suitably outraged by the Bag One images.

Without an ounce of irony, the case opened at Marlborough Street Magistrates Court on April Fool’s Day. But it wasn't open for long. Inspector Luff was able to present a “housewife,” also a Justice of the Peace, who told the court, “I couldn't believe what I was looking at. I suddenly felt I could not stay in the gallery any longer. I realized I was red with embarrassment.” An accountant revealed his own reaction. “I felt a bit sick that a man should draw himself and his wife in such positions,” he told the court. “It was a shock to see Yoko in the nude with a rather exaggerated bosom with apparently somebody sucking a nipple.”

Luff himself was forced to admit that he "saw no display of annoyance from the younger age group” when he raided the gallery, where about 40 people were looking at the lithographs. “But one gentleman was clearly annoyed," he noted. Asked by the magistrate if the gentleman had stamped his foot, Luff replied, “Anger was definitely registered on his face.” He also argued that "many toilet walls depict work of similar merit. It is perhaps charitable to say they are the work of a sick mind.”

Neither Lennon nor Ono was in court for the hearing; in fact, they were in Denmark - a nation known at the time for being a distributor of the kind of stuff the Dirty Squad was commissioned to deal with. The couple wasn't present to remark upon the surprising decision by the establishment to charge the gallery under the U.K.’s Obscene Publications Act of 1964; instead it proceeded under the Metropolitan Police Act of 1839.

While the newer law covered the situation in detail, the relevant part of the older law made it an offense to distribute indecent material on a “public thoroughfare.”

That didn’t give the presiding magistrate much to work with, since a gallery could not be said to be a thoroughfare. Giving his decision later, St. John Harmsworth observed that the Metropolitan Police Act referred specifically to “passengers” being involved in any alleged crime. “As I understand the word 'passenger,' it means someone on the move … people who enter the gallery are not passengers - they then finish, for the time being, passaging," he noted. "If, of course, the action had been taken under another act, it might have been a different kettle of fish.”

For decades, the question remained as to why the Director of Public Prosecutions decided to pursue the gallery under the older law, rather than one specifically designed for such alleged offenses. A clue appeared in 2004, when the U.K.’s National Archives released a letter written in the days after the raid by another English artist, P.F.C. Fuller, who advised the Director of Public Prosecutions, “There are thousands of prints by Rembrandt … depicting sexual intercourse, so at least one such print will figure in all the important State and private collections. ... Whatever happens regarding the 'Lennon Lithos', this case will certainly cause collectors to regard the outcome with interest. I understand that the queen has some highly erotic work by Fragonard.”

One can … imagine … the establishment’s concern over the idea of Her Majesty’s name being brought into an obscene publications trial and used in the defense in any subsequent action. To have a new connection made between the queen and Lennon after he'd returned his MBE honor just months previously would not have gone over well.

The head of state was not mentioned in the hearing, but the possibility was at least pointed to when Inspector Luff was shown a work by Picasso and was forced to agree that Lennon’s material bore some resemblance to the Spanish artist’s output.

Afterward, Schuster declared himself happy with the result, noting that, even though the action had cost him £10,000, he expected to recoup it from sales related to the publicity. Lennon was also working on a new set of lithographs, which, perhaps predictably for such a willful creative, turned out to be far less controversial. Today, those original Bag One works can change hands for £10,000 each.

The Best Song From Every John Lennon Album

More From Ultimate Classic Rock