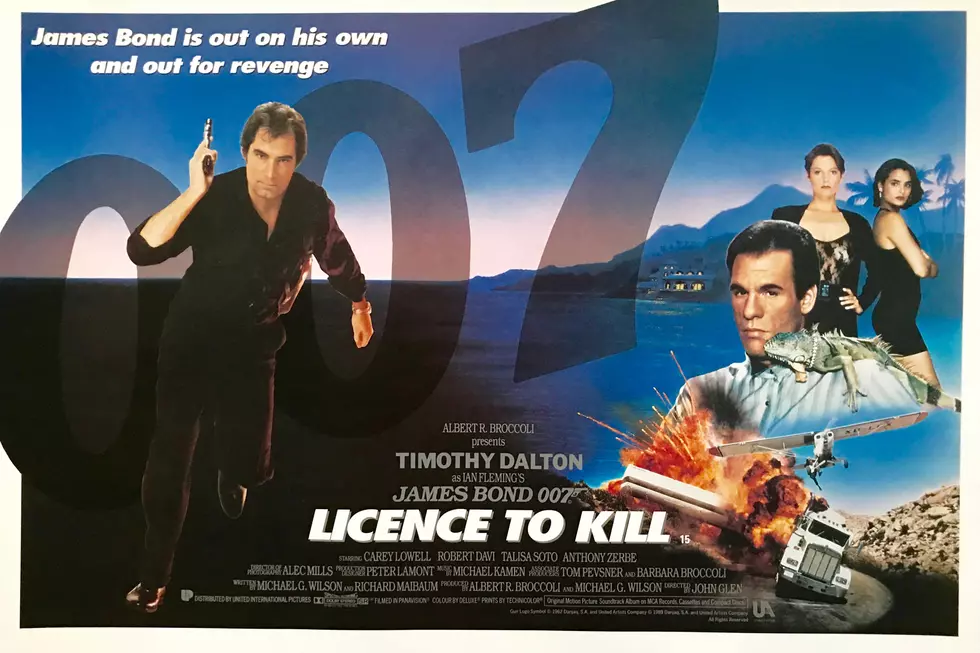

How ‘License to Kill’ Almost Murdered the James Bond Franchise

James Bond was severely outgunned.

Since its debut with 1962's Dr. No, the spy franchise had been the flag bearer for big-event movie making, with each installment setting new standards for exotic globe-trotting locations, gadget-laden sports cars and groundbreaking stunt work.

But by the time of the series' 16th adventure, 1989's License to Kill, 007 was in danger of being left behind by a new wave of silver-screen icons, including Indiana Jones, Marty McFly and Batman. Event movies were becoming much more common - and the effort, star power and money it took to stand out from the pack were increasing every year.

The end of the Cold War was also well underway by the time License to Kill was being written, with the Berlin Wall falling four months after the film's July 14, 1989, release. This made the series' ongoing tradition of Russian bad guys at least temporarily obsolete, a big change to the political undercurrent that had informed Bond films from 1963's From Russia With Love all the way up through 1987's The Living Daylights.

Latin-American drug cartels had instead become Hollywood's new go-to villains, as evidenced by the success of movies and TV series such as Lethal Weapon and Miami Vice. The opulence and humor that had become a hallmark of Roger Moore's 007 era had also fallen out of favor, with moviegoers favoring grittier action and emotions.

All in all, it was a pretty tricky time for Timothy Dalton to try and establish himself as the fourth James Bond, a process he began with The Living Daylights. While his grounded, less-humorous debut performance was fairly well received, the film made less of a positive impression.

After abandoning a more ambitious and expensive plan to film in China for the first time, producers decided to keep costs down and ratchet up the emotion and violence by having Bond go rogue. He quits the MI6 to seek revenge on the drug lord Frank Sanchez, who feeds the leg of 007's best friend to a shark after killing his new wife at the beginning of the movie.

"United Artists wasn't increasing the Bond budgets for an entire decade, as all the films between [1979's] Moonraker and License to Kill were budgeted in the $30 to $40 million range," author Charles Helfenstein noted in Nobody Does it Better: The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of James Bond. "The production team needed to shave costs, and so Mexico was chosen instead of China."

Watch 'License to Kill' Trailer

In retrospect, it's hard not to notice the budget-conscious approach in the often darkly lit, generically staged film, with production values that sometimes seems more suited for a TV movie instead of the big screen.

But Sanchez's ruthlessness was too shocking for network TV at the time. In addition to the shark maiming, he also kills a henchmen (who, incidentally, didn't do anything wrong) by blowing his head up like a balloon in a decompression chamber - and the audience isn't spared any of the resulting blood and gore.

Bond doesn't pull any punches either. When a bad guy is trapped in a shark tank, 007 tosses him a briefcase full of money instead of a rope; in another scene, he shoots a villain with a speargun and then takes the scuba gear from the still-breathing man while he's in the water.

The lean, mean License to Kill was greeted with mostly positive reviews, with Roger Ebert saying Dalton "makes an effective Bond - lacking Sean Connery's grace and humor, and Roger Moore's suave self-mockery, but with a lean tension and a toughness that is possibly more contemporary."

But the movie was quickly forgotten at the box office, finishing the year as the 36th most popular movie in the U.S., with only $34.6 million in ticket sales. By comparison, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, co-starring original 007 Connery, was the second biggest movie of the year, earning more than $197 million. Adjusted for inflation, License to Kill is the lowest-grossing film in Bond franchise history.

Regardless, plans were soon underway for a third Dalton-fronted 007 title, scheduled for release in 1991 as Property of a Lady. But a protracted legal battle stemming from the sale and eventual bankruptcy of the series' distribution company, MGM, put the project on ice for four more years. This delay between movies ended Dalton's time with the series after just two films and left its entire future up in the air.

But eventually all issues were resolved, and James Bond returned in the form of Pierce Brosnan with 1995's Goldeneye. This time, 007 was better equipped for the increasingly competitive box-office race with a production budget of $60 million, nearly double what was spent on License to Kill.

James Bond Movies Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock