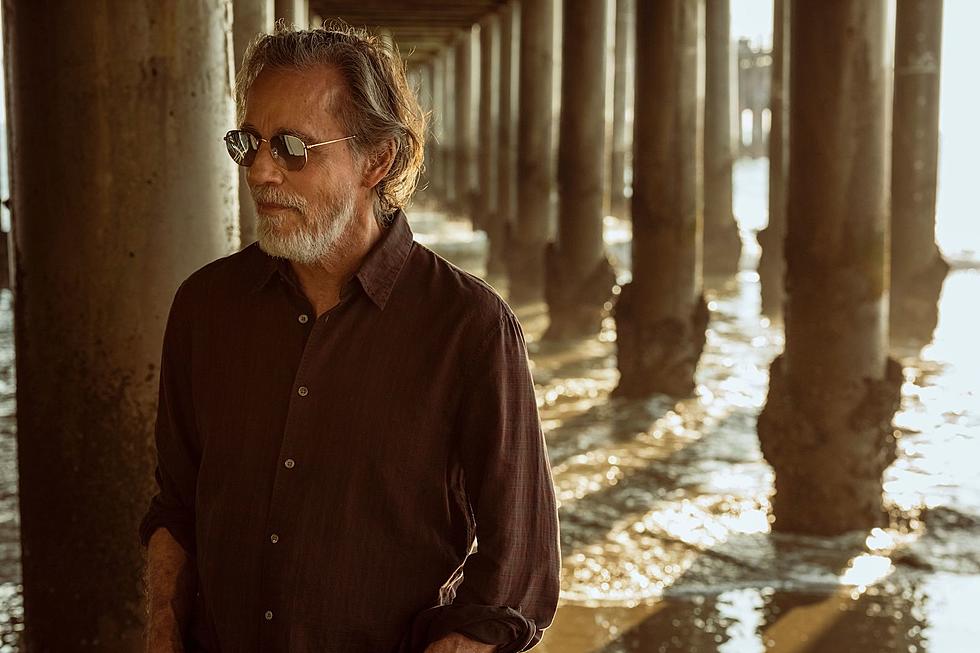

How Jackson Browne’s Creative Retreat on ‘Hold Out’ Became His First No. 1

Up until Jackson Browne's sixth album, the singer-songwriter was pretty much adored by critics. Hailed as one of the brightest artists of the '70s Los Angeles scene that spawned an entire genre of music in the decade, Browne grew bolder with each work.

After three albums of increasingly personal songs that matched smart lyrics with even smarter melodies, Browne made 1976's The Pretender, a requiem to his late wife, who died the previous year. His next album, 1977's Running on Empty, was a concept album about being on the road that was recorded onstage, backstage, in hotel rooms and on tour buses.

So, when Browne took a three-year break between records and resurfaced on June 24, 1980, with Hold Out, expectations were high – from both critics and fans, who pushed Running on Empty to No. 3 on the album chart, an all-time best showing. But instead of taking his musical adventures into new territory, Browne retreated on Hold Out, checking in with a collection of songs that lacked the bite and pull of his best LPs.

Recorded in L.A. during the fall of 1979 through the spring of 1980, the album doesn't sound all that different than Browne's earliest work, particularly 1972's self-titled debut and 1973's For Everyman. But with success, acclaim and apparently the clout to make whatever kind of record he wanted to at this stage of his career, Browne chose to fall back on some old crutches.

Worse, he seemed to take the things his critics disliked most about his music and constructed an entire album out of them. Then he threw the unconvincing and bloated "Disco Apocalypse" at the start of the record and hoped listeners would follow him. It wasn't an especially inviting opening, but it more or less set the tone for the album, which is, by turns, unconvincing and bloated.

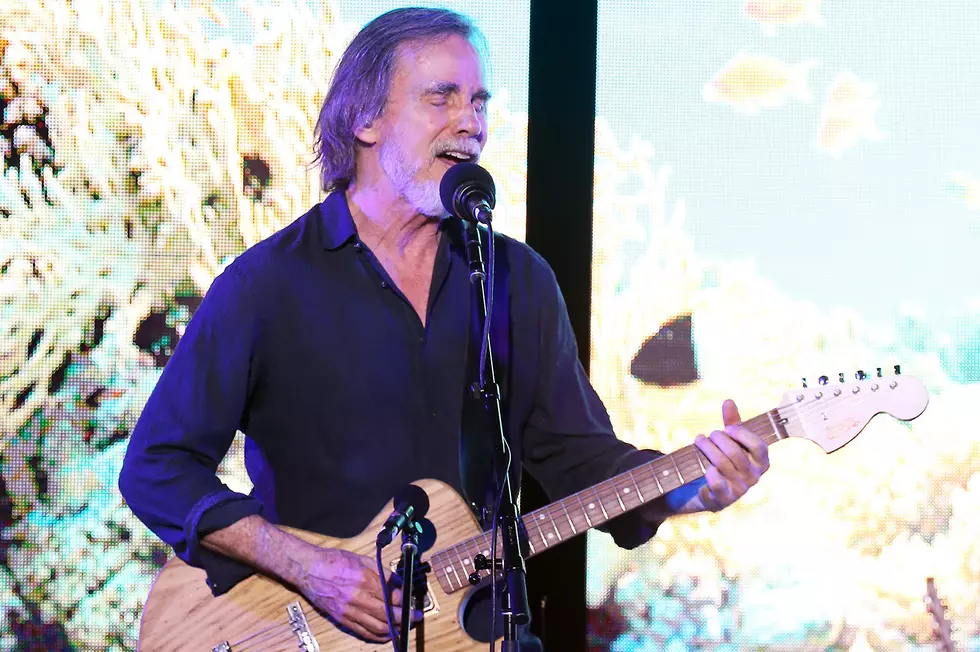

Listen to Jackson Browne Perform 'That Girl Could Sing'

For almost 40 minutes, Browne winds his way through a record that never quite finds its purpose. Its good songs – "Boulevard," "That Girl Could Sing," "Hold On, Hold Out" – are merely good; the bad songs (like "Of Missing Persons," a tribute to Little Feat's Lowell George, who died in 1979) are terrible.

The one stuck in between, the title track, is made pointless and forgettable after the eight-minute closer and similarly titled "Hold On, Hold Out" (even though the latter comes with a spoken-word interlude that may be the most embarrassing thing Browne has ever recorded).

None of this seemed to bother fans as much as it did critics, who slammed the album. Hold Out shot straight to No. 1 – becoming Browne's first and only chart-topping record. It eventually sold more than two million copies, making Hold Out his third biggest-selling LP behind Running on Empty and The Pretender. "Boulevard" and "That Girl Could Sing," despite their clumsy wordplay and questionable production tricks, were both released as singles and hovered around the Top 20 for a few weeks.

The next time Browne reached the Top 40, two years later, he had the biggest single of his career: "Somebody's Baby," from the Fast Times at Ridgemont High soundtrack, reached No. 7. A year later he returned with Lawyers in Love, a record designed to break him from the L.A. singer-songwriter tag he began rebelling against years earlier.

In that respect, the album did cut his ties with the scene that made him a star, and its musical and lyrical detours are questionable at times. But Hold Out had already erased most of that glow, effectively ending Browne's golden era with a slight imitation of it.

Top 40 Singer-songwriter Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock