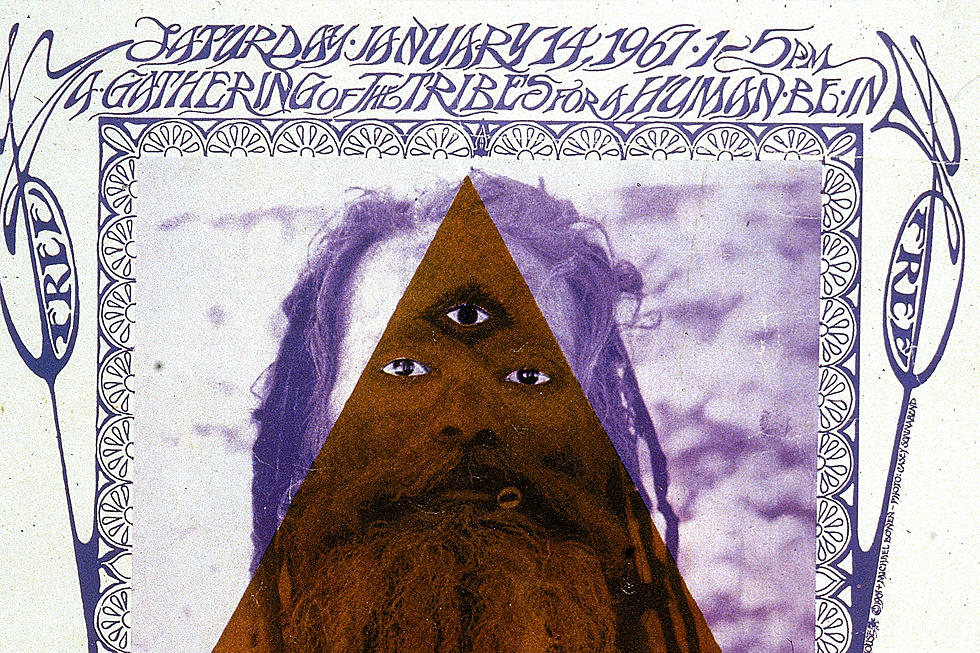

55 Years Ago: Hippies ‘Turn on, Tune in, Drop out’ at Human Be-In

“'Welcome,' said a calm voice from the platform. ‘Welcome to the first manifestation of the Brave New World.’ And a kind of collective sigh came from his audience. Could this be true? Could it be really true? Here we were - 20,000 blown minds together - gathered for nothing more than love and joy, to celebrate our oneness, in a lovely park on a sunny day, along with the people who looked like us, who thought like us, who shared our hopes and our idols, whose one wish was to be left alone to dig life. The afternoon brought many surprises.”

So wrote East Village Other's Oliver Johnson in the edition that followed San Francisco’s Human Be-In event of Jan. 14, 1967. And while the youthful revolution didn’t achieve all it set out to do – like others before and after it – the success of the Be-In was enough to cement the concept of ‘60s counterculture in world history, paving the way for the Summer of Love, Woodstock and the iconic artworks inspired by the hippie movement.

Before the Human Be-In, there had been other “–in”-style events including sit-ins and teach-ins. The pun that gave the event its name was a chance remark during the Love Pageant Rally on Oct. 6, 1966 – the day LSD became illegal in the state of California, overseen by newly elected Republican governor Ronald Reagan. Since much of the flourishing alternative art movement was based in San Francisco, it seemed the obvious place to continue to apply pressure. So artists Allen Cohen and Michael Bowen, who staged the pageant, decided that their follow-up event would have a specific purpose.

“We had realized that the change in consciousness and culture we were experiencing had to be communicated throughout the world,” Cohen wrote later.

“We felt that the ideals of Peace, Love and Community based on the transcendental vision could transform the world and end the war in Vietnam. In short, we wanted to turn the world on. ... The anti-war and free-speech movement in Berkeley thought the hippies were too disengaged and spaced out. Their influence might draw the young away from resistance to the war. The hippies thought the anti-war movement was doomed to endless confrontations with the establishment which would recoil with violence and fascism. We decided … we had to bring the two poles together.”

Cohen and Bowen engaged with “opposing” activists Jerry Rubin, Max Scherr and others, and secured their support. “The days of fear and separation are over,” Cohen wrote in a letter. “Now that a new race is evolving in the midst of the old, we can join together to affirm our unity and generate waves of joy and conscious penetration of the veil of ignorance and fear that hides the original face of humankind.”

As a result, the “union of love and activism” was an overwhelming success,” he said. “Over 20,00 people came to the Polo Fields in Golden Gate Park. The psychedelic bands played: Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead and Quicksilver Messenger Service. Poets Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Michael McClure, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Lew Welch and Lenore Kandel read, chanted and sang.” Psychedelic psychologist Timothy Leary caught the spirit of the moment when he asked the crowd to “Turn on to the scene; tune in to what is happening; and drop out – of high school, college, grad school, junior executive, senior executive – and follow me, the hard way.” The abbreviated version “Turn on, tune in, drop out” became a timeless slogan.

Watch Archive Footage of the Human Be-In

All the bands played for free – although many had already been doing so in the San Francisco area in a bid to keep momentum among the ever-increasing hordes of young people coming to the area to be part of the new scene. “The first really pure event was the Be-In, which was the first time that the whole head scene was actually out in force,” Grateful Dead leader Jerry Garcia told Rolling Stone in 1972. Jefferson Airplane’s Grace Slick told The Guardian in 2017 that the entire movement was a single question: “Do you want to hang out and experience the boredom of the 1950s, or do you want to turn everything on its head and live like they did in Paris at the end of the 19th century?”

She added that “Paris sounded like a lot more fun. So that’s what we did: turned things upside down. It was also an extension of the understanding that to whom much is given, much is expected. We get paid very well as rock ’n’ roll musicians. So you give it back. You play free. And we played free in the park a lot that summer. It was a party.”

At the most ambitious end of the spectrum – demonstrating just how far out of the box the movement was prepared to go – there was even a discussion about “directing magical and conscious energy towards the Pentagon in order to overcome its impregnability as both the symbol and seat of evil,” Cohen noted. “The idea to exorcise the Pentagon would be realized in the March on Washington in October where we warned that we would form a ring of hippies with joined hands around the Pentagon and raise it 15 feet in the air and turn it orange.” One commentator helped explain that such an outlandish concept was right at home in a movement that aimed to strengthen “personal empowerment, ecological awareness and higher consciousness.”

The Be-In – which notably drew almost no police presence, despite reports of San Francisco cops frequently doling out heavy-handed treatment to hippies – was the first counterculture event to grab global headlines, and in doing so it certainly achieved its ambition of raising the question of what the world’s future could look like without reliance on concepts of empire, dominion and war. “Soon there would be Be-Ins and Love-Ins from Texas to Paris,” Cohen said. "And the psychedelic and political aspects of the youth culture would continue to grow hand in hand everywhere.”

In his East Village Other article, Johnson quoted political activist Scherr saying, “There was great potential there for protest. If I could have gotten to a microphone, I would have said what it in my heart. The organizers implied that they were against the war but that they didn’t want to bother people about it on this occasion.” Johnson wrote that he understood the idea that if you wanted to end the war “you’ve got to straighten out your own heads first.” He acknowledged the question “How can we ever have a groovy, happy society unless everybody in is has reached [their] own nirvana?” But he countered it with, “What happens in the meantime – do people go on getting tortured and shot and burned alive?” He went on to allow that, no matter what, the Be-In had proved there was a “potent force” that was “just waiting for direction.”

Perhaps with several turns of generation between then and today – at a time where the world could be at risk of “canceling” itself through an inability to find ways to share ideas of change without anger and tribalism – it’s easy to view the Be-In’s aims as naive. Yet they continue to return to express themselves again in new phrases, new art and new media. That might be evidence there’s a valid point at the heart of the discussion.

Watch a Montage of Grateful Dead at the Human Be-In

“We all knew that the following summer there was going to be a lot of people coming, and we tried to prepare for that,” Garcia said of the Be-In’s aftermath. But the problem was “too many people to take care of and not enough people willing to do something. There were a lot of people there looking for a free ride – that’s the death of any scene when you have more drag energy than you have forward-going energy.”

Slick noted that "the ideas we had in the ‘60s, leading up to the Summer of Love, are self-sustaining. Most people want to enjoy themselves. Most people want integration. Most people want to live a sustainable existence. With 8 billion people in the world, you have to care about each other. We were like a tank; we were going to keep plowing through this thing until we effected change. It seemed inevitable.”

“I thought we’d just about wiped racism out, and now look at how it is,” David Crosby said in 2019 when asked if the’60s were a “dream that didn’t come true. “I think it goes back and forth – I’m hoping that’s how it is. What’s going on now is very, very bad. But I don’t think the things we espoused in the ‘60s were wrong: that love is better than hatred, that peace is better than war. I think those are true; I don’t think we were wrong about any of those.”

Top 100 '60s Rock Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock