How Classic Rock Survived the ’80s

Trends and technology have always had an impact on pop music. But during the '80s, those forces combined to change the industry in ways that often sounded — and looked — like they'd altered the rock 'n' roll landscape forever.

Those changes didn't happen in a vacuum, and they didn't take place overnight. For decades, engineers and artists had sought to capture a cleaner, more natural sound on their records, while gaining a greater degree of control over the recording process. During the '70s, multi-track technology truly started coming into its own. Although artists at the vanguard had been able to stretch professional studios to their limits during the '60s, with acts like the Beatles and the Beach Boys using cutting-edge methods to send rock in startling new directions, the following decade saw a great leap forward in recording — even equipment available to the amateur or hobbyist.

Where Phil Spector's "Wall of Sound" had served as the sonic benchmark for a prior generation, the next wave of gear enabled artists to break their music down brick by brick with an ever-greater degree of precision. Although audiences still placed a premium on the raw energy that launched the genre, that old-fashioned sloppiness was increasingly crowded out on the pop charts, where a raft of singer-songwriters, along with bands like Fleetwood Mac and the Eagles, kept a foot in the rock world while furthering the pursuit of perfect sound.

As the limits of studio technology dwindled and the demands of the marketplace increased, a number of acts managed to find a happy medium between rock's traditions and its emerging sounds. Boston, for one, helped pioneer the subgenre later scornfully dismissed as "corporate rock" with its meticulously recorded debut LP — and opened the ears of generations of artists, producers, and engineers who used that sound as a template for some of the next decade's most successful releases.

"You listen to 'More Than a Feeling' and then some of the stuff we were doing, and it’s almost like part two of that, if you like," Def Leppard guitarist Phil Collen told Guitar World. "Boston had incredible vocal sounds and the guitars were great. A Boston record is so well recorded and it does everything it’s supposed to. At the end of the day, it wins all around."

It wasn't just the increasingly precise control of the studio environment that helped produce rock's emerging new sound, either. Parallel to the new multi-track tools being developed, producers were also gaining access to an incredible array of technology — much of which was then used in unexpected, paradigm-shifting ways. For example, while engineering Peter Gabriel's third solo album, Hugh Padgham turned on the talkback mic built into the new SSL console in an attempt to talk to drummer Phil Collins during his performance, only to discover that the compressor built into the channel gave Collins' drums a massive new sound.

Listen to Peter Gabriel's 'Intruder"

"The whole idea was to hang one mic in the middle of the studio and hear somebody talking on the other side," explained Padgham. "And it just so happened that we turned it on one day when Phil was playing his drums. And then I had the idea of feeding that back into the console and putting the noise gate on, so when he stopped playing it sucked the big sound of the room into nothing."

That sound ended up having a huge impact on the mainstream rock drum sound for the decade — as did another piece of Gabriel-affiliated technology, the Fairlight synthesizer. One of the most popular and influential digital sampling instruments of the '80s, it allowed artists to isolate and manipulate sound in ways that once seemed like science fiction. Gabriel, ever an enthusiastic adopter of new technology, was among the first to use and invest in the Fairlight, although — just as with Collins' new drum sound — he had no idea what he was helping unleash.

"It was one of the early Fairlights, and in typical Gabriel style, you know, if I want a pint of milk I buy the cow. I’d always dreamed of being able to grab a sound and do what you wanted with it," Gabriel told Uncut. "‘Modern’ was good. But ‘different’, really. Particularly with the third album, I was trying to find my own path."

Along with the Fairlight and similar instruments like Yamaha's DX7, programmed drums reached a turning point in the early '80s, with E-mu's Drumulator and the LinnDrum among some of the more popular options for acts seeking to keep perfect time. As founding Chicago drummer Danny Seraphine later pointed out, the growing clatter from these machines created no small amount of tension for the living, breathing guys holding the sticks; Seraphine himself ended up learning how to program in an effort to gain a little extra job security.

"It really put the drummer in a very subservient position. People started really bashing drummers, you know? Keyboard players, especially. It was terrible. 'We've got a machine now that's gonna replace you guys and it doesn't talk back, it keeps perfect time, and we can program it to play exactly what we want,'" Seraphine recalled. "And then I started hearing all these records that were being programmed by what I could tell were keyboard players — non-drummers. You could just hear it. So I said to myself, 'Well, you can fight it or you can learn it and take it to another level,' so I bought one, and we were off the road for quite awhile, so I just took it and learned it inside and out. And then I got myself this really extravagant MIDI setup, with pads, and a computer, and the whole shot, and in fact I just put my sticks down and started programming, because I thought, 'S---, if I want to hear better programming, then I better do it myself.'"

Drummers felt an outsized adverse impact during the early synth era, but they were far from the only musicians affected. For a generation of younger acts, the democratization of sound promised by the emerging technology proved even more alluring than the excitement of starting an old-fashioned garage band; instead of double-necked guitars, millions of young players aspired to banks of keyboards, monitors and MIDI controllers. For a lot of kids, the early-to-mid '80s were defined by the New Wave — and synthesized sound. In an effort to remain relevant, just about every mainstream act dabbled in digital during the decade, and although those efforts produced hits for plenty of veteran artists, not all of them emerged unscathed.

In fact, for a number of artists, fitting in with the '80s meant drastic and occasionally disastrous changes. Alice Cooper suffered through a difficult start to the decade before finding his feet in its waning years, while Neil Young bewildered a segment of his fan base with 1982's experimental Trans. Yes achieved some of their greatest sales success by sounding virtually nothing like themselves — as did ZZ Top, folding synths and programmed beats into their traditional Texas boogie.

"By no stretch of the imagination did it come close to the word traditional," said ZZ Top frontman Billy Gibbons of his band's own '80s hits. "This was experimentation at its zenith. And at the same time, you could stack the room with the latest technological breakthroughs, and we've still got one foot in the blues."

Listen to ZZ Top's 'Velcro Fly'

Further fueling these changes was the massive popularity of the new cable network MTV, which launched on Aug. 1, 1981, with a playlist that included Pat Benatar, Rod Stewart and the Who. Promo clips for singles were nothing new, but with the rise of cable TV, there were more programming hours to fill — and millions of kids to woo with music videos that added a whole new (and brilliantly effective) marketing hook to the music. Although labels had never exactly shied away from signing good-looking performers, MTV placed an even greater emphasis on an artist's image.

The shift was easier for some artists to navigate than others. For a number of acts, the camera just wasn't an ally, no matter how creatively off-the-wall directors tried to get; for others, it proved a potentially career-destroying pitfall. But even for the veteran rockers who managed to turn MTV to their advantage during the '80s, the network's constant demand for singles fodder could be a double-edged sword.

"There's a discrepancy between perception and reality in our work from the '80s," argued Genesis guitarist Mike Rutherford. "Not every song on every album was radio-friendly and designed for maximum airplay. We always had two or three songs that were 10 minutes long and ventured about. But MTV came along and dwarfed the idea of anything else we did, choosing to focus on our three-minute pop songs. Thus the public perception. I wish it hadn't happened that way, but it's too late to turn back now."

The difficulties of the music video era were arguably hardest for female performers, who were pressured to exploit their sexuality in progressively more provocative ways — or to pursue standards of beauty regardless of the impact on their health or overall well-being. For acts like Benatar or Heart, the line between remaining sane and remaining relevant could have a razor's edge.

"All of a sudden, you had to not only sound good and be good, but you had to look fabulous and be able to act on some level, or at least lipsync. Nobody was really prepared for that," Heart's Ann Wilson told Ultimate Classic Rock in 2015. "I think that we at some point made a decision that it was more important to us to be ourselves then to not be ourselves and get bucketloads of money. Because you can make that devil’s bargain and they can back the dumptrucks of money up to your house and it can be really unhappy behind it."

In addition to the stress of dealing with corsets, dry ice and wind machines, artists faced increasing calls to use material from outside writers in an attempt to bolster their odds of scoring another hit. For bands like Heart and Chicago, professional songwriters like Diane Warren and Tom Kelly & Billy Steinberg helped keep them on the radio at a time when they might have otherwise struggled — but those hits came along with an increasing amount of criticism from fans who cried sellout, as Starship learned after hitting No. 1 with "We Built This City" in the fall of 1985. And even before hearing complaints from record buyers, the artists themselves often bristled at being told what to do.

"I could appreciate the band’s point of view," songwriter Bob Mitchell recalled of his years as an outside contributor. "I’d walk into the rehearsal room and say, 'I know you’re going to hate me, but I’m being forced into this situation too, so let’s just find a little common ground here.' I’d try and find the two members of the band — the main writers — and try to get on with them. I’d say, 'We have to find some way of making this work, otherwise your managers are going to get pissed with you, and my publisher is going to be pissed with me.'"

"Starship, in a way, became a poster band for that era and that whole kind of dissatisfaction that a lot of critics and fans had with what was happening with rock music at that point in time," frontman Mickey Thomas admitted. "'We Built This City,' in particular, became the poster child for that, and was held up as everything people didn’t like about the music at that point in time. It became a double-edged sword, you know? We set out to make songs that were more commercial, and we achieved that, but at the same time, you do lose a little of your integrity along the way."

But for other acts, the benefits of working with professional songwriters outweighed any drawbacks. After struggling through much of the '80s, Aerosmith's freshly reunited — and sober — classic lineup sought to improve on the disappointing sales of 1985's Done With Mirrors LP by bringing in outside help for the follow-up, 1987's Permanent Vacation. The results served as something of a textbook example of how a veteran rock act could balance its legacy against the need to deliver new pop hits, with rougher-edged originals up against pop anthems and power ballads co-penned by Desmond Child, Holly Knight and longtime Bryan Adams collaborator Jim Vallance.

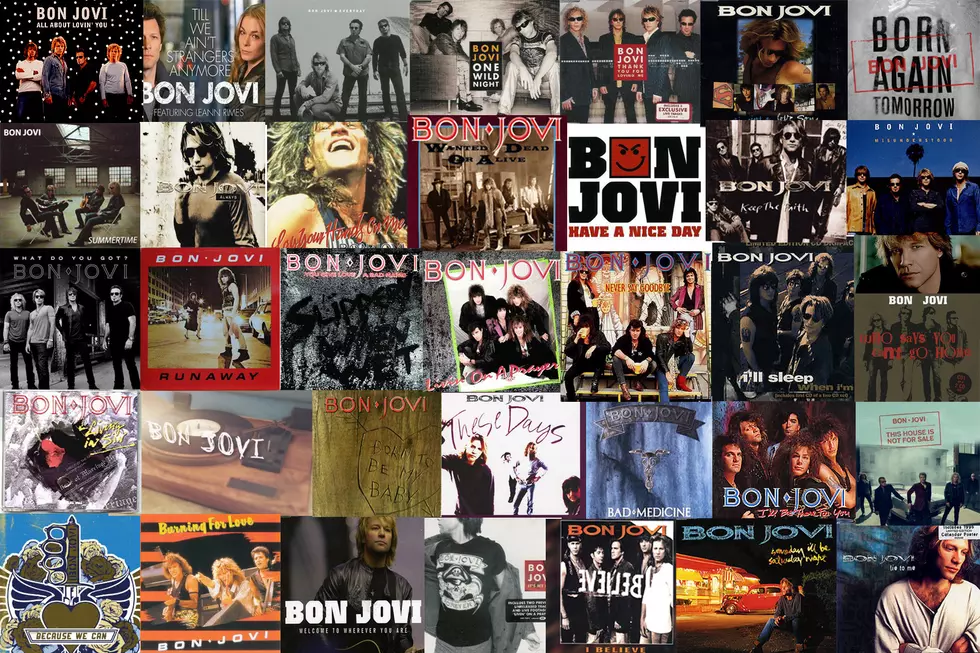

Child in particular proved an adept writing partner for a number of popular '80s acts, delivering hits for Kiss, Bon Jovi, Alice Cooper and Ratt, among others, but he was hardly alone — toward the end of the decade, rock acts who didn't record outside material were arguably outnumbered by those who did. Over time, their efforts inevitably followed an audible formula.

Ultimately, in their efforts to embrace new sounds, many of the decade's biggest records ended up sounding dated. What felt new and fresh at the dawn of the '80s had become formula toward their end, and yet another new generation of artists stood ready to take up their instruments in an effort to take rock in any number of different — but generally less produced — directions. The pristine, synth-assisted sound of the rock mainstream was poised for a major course correction courtesy of the subgenre initially known as "modern rock" and later simply referred to as alternative.

"We wanted to make records that were timeless, and we rejected anything that would make them sound dated," R.E.M.'s bassist, Mike Mills, told Pitchfork in 2011. "When we made Murmur and Reckoning, every band in the world was using a Yamaha DX7, which we despised. The sound of it was just miserable. While I love a lot of that popular synthetic music, we didn't want to sound like that, because when you hear it now you think, 'Oh, 1983!'"

Still, for all its flaws and all its excesses, the '80s remain a musical touchstone for millions — including the fans who bought the records as well as a number of artists who will forever be tied to their work during the decade. The "melodic rock" of the era was driven underground in the '90s, but the sound remained popular in other parts of the world, and it's made a comeback in recent years. And while a number of the biggest rock bands of the '80s have openly struggled with how to fit their hits of the period into their legacy — or even what they're supposed to sound like in the 21st century — there are reasons those songs still resonate, big production and all.

"Great music wins out every time, I don't care when it was written," Chicago co-founder Walt Parazaider told Jam Magazine. "You have to be adaptable in this business. We had our greatest success as a band selling records during the '80s because we were willing to change."

30 Most Outrageous '80s Rock Fashions

More From Ultimate Classic Rock