How Harry Nilsson Found the Promised Land on ‘Nilsson Schmilsson’

It's always a good idea to be careful what you wish for, especially if you're a brilliant singer-songwriter with self-destructive tendencies. Harry Nilsson learned that far too well with Nilsson Schmilsson.

Nilsson made his debut as a recording artist in the late '60s, releasing a string of critically acclaimed but commercially ignored LPs that included Pandemonium Shadow Show, Aerial Ballet, and the descriptively titled Randy Newman covers set Nilsson Sings Newman. Undaunted by his disappointing sales — and presumably emboldened by public proclamations of support from members of the Beatles — Nilsson expanded his ambitions for his sixth studio effort, The Point!, released in early 1971.

A song suite built around the family-friendly story of a round-headed boy named Oblio who's ostracized in a land where everything has a point, the album — aided by an accompanying animated film — gave Nilsson his first taste of Top 40 success on the U.S. albums chart while adding another single, the No. 34 "Me and My Arrow," to his growing string of radio hits. But it was all a warm-up act for the breakthrough that was shortly to follow.

Looking for a change in his sound, Nilsson — who'd self-produced much of his earlier work, some in conjunction with producer Rick Jarrard — hired Rick Perry, a veteran of the boards for a diverse array of artists that included Captain Beefheart, Fats Domino, and Tiny Tim.

Bringing Perry into the equation took Nilsson out of his comfort zone in a number of ways. Geographically, the sessions transplanted him to London, where he and Perry's band of studio ringers set up shop at Trident. The new producer's influence ran deeper than a fresh set of ears and a new spot on the map, however.

Listen to Harry Nilsson Perform 'Gotta Get Up'

Nilsson wasn't exactly lazy in the studio — he'd tracked towering stacks of his own vocals for Nilsson Sings Newman, for example — but he had, like any artist, a tendency to lack objectivity toward his own work, as well as a restlessness that sometimes prompted him to abandon recordings that might deserve a little extra attention. With Perry holding the reins, Nilsson's next record was bound to have more focus and added polish — even if he had to fight it out of his headstrong and occasionally reluctant artist.

This tug of war is perfectly represented in the behind-the-scenes battle over one of the album's three cover songs: "Without You," a tune lifted from Badfinger's No Dice LP. Handed the song, Nilsson banged out a raw, transcendent demo, but wasn't entirely sold on whether to put the song on the record — and definitely wasn't interested in yielding to Perry's vision for the final cut, which included a string section and another pass at the vocals. After tussling over it in the studio, the two attempted a tête-à-tête, with mixed results.

"Like two proper gentlemen, we decided to have a meeting over high tea at the Dorchester Hotel to discuss what we were going to do," Perry said in Nilsson: The Life of a Singer-Songwriter. "And I said, 'Harry, you do remember that when you came to me and asked me to produce you, my only condition was that I have control, creative control?' And he looks at me dead in the face and says, 'Well I lied!' ... Without another word, we jumped into a taxi down to the studio. He ran right out and sang the vocal that you hear on the record."

That dynamic, in a nutshell, is the story of what would become Nilsson's seventh studio album. Released in November 1971, Nilsson Schmilsson showcased his creative dichotomy more cleanly and clearly than previous efforts, with Perry's disciplined production serving as a satisfying foil for Nilsson's increasingly untethered approach.

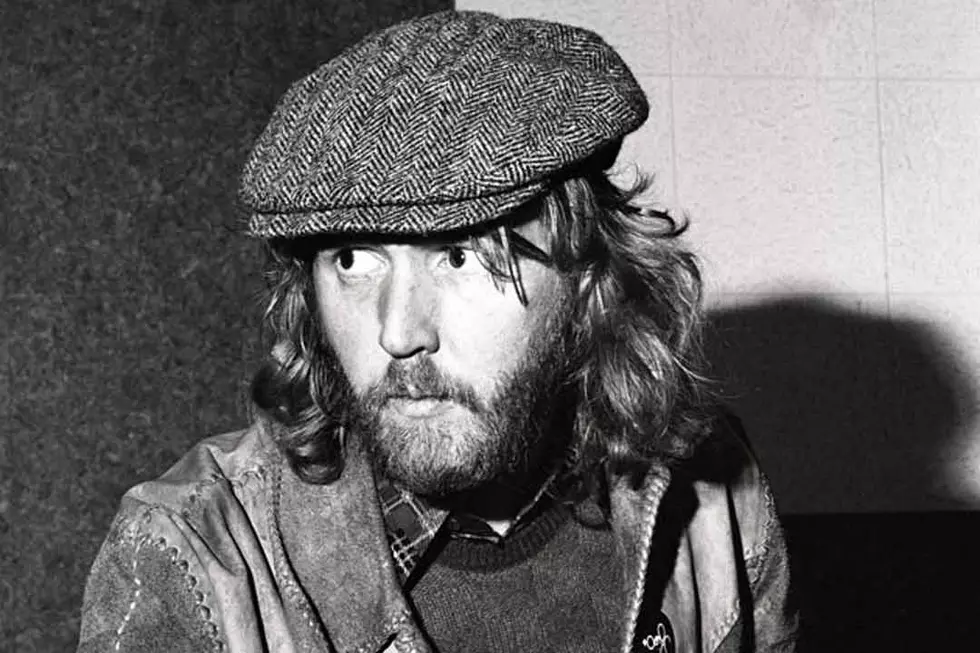

Under the tongue-in-cheek title — and the slightly blurry cover photo of a rumpled Nilsson standing in the kitchen, wearing a robe and clutching a pipe — the record boasted all the smart, tuneful songcraft that had earned him the Beatles' famous ardor, buttressed with eclectic arrangements that couched its darker moments and sent its more commercial elements soaring into the stratosphere. Leading it all was Nilsson's angelic tenor — the perfect vehicle for mournful ballads like "Without You" as well as occasionally profane pop songs like the jaunty "Gotta Get Up."

Listen to Harry Nilsson Perform 'Without You'

Befitting a record whose sonic contours were shaped by a producer bridling an artist used to getting his own way, Nilsson Schmilsson also came together in a hurry — at least on the lyrical front, where Nilsson was obliged to come up with words to songs he hadn't had at the ready when work on the album started. As often as not, the lyrics to Nilsson's Schmilsson tracks didn't really come together until it was time for him to put them to tape.

"He lay down on the floor of the studio propping himself up on his elbow with his head resting on his hand, and a sheet of paper on the floor and started to just write the lyrics. And so in 15 minutes he had lyrics," Perry said in Nilsson: The Life of a Singer-Songwriter. "He had no alternative. He was forced to do it. We had to do the vocals and we had to move on. So that’s how most of the songs for that album came about."

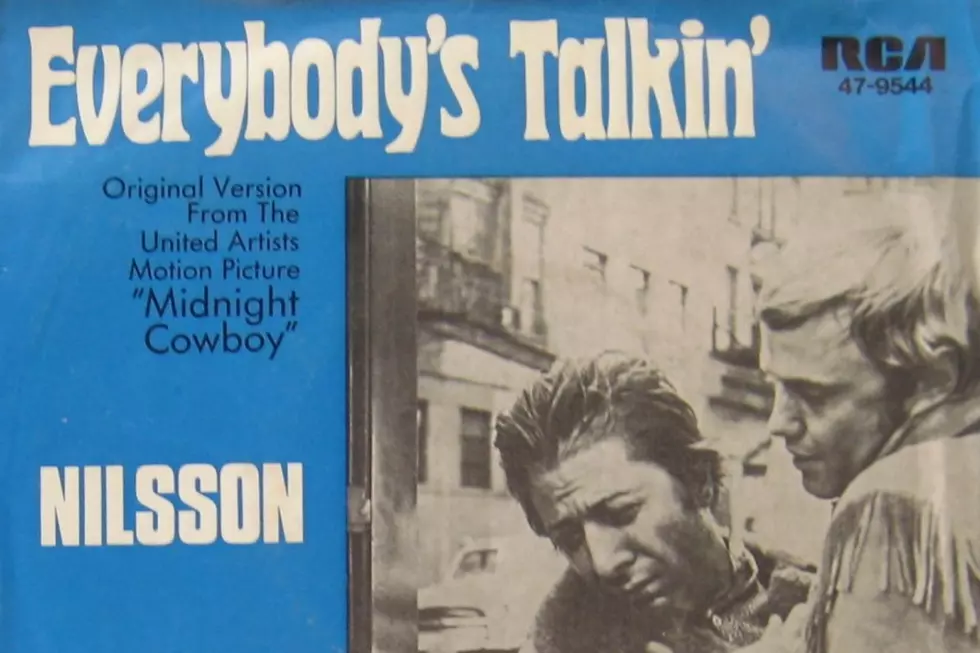

If the prep work was occasionally somewhat slapdash, the end results were inarguable. Far and away the biggest hit of his career, Nilsson Schmilsson peaked at No. 3 in the U.S. and landed a spot lower in the U.K. — largely because of "Without You," which gave Nilsson his first and last No. 1 single.

And the album wasn't done there, either: the riotous "Jump into the Fire" also worked its way into the Top 40, while the borderline novelty record "Coconut" — which found Nilsson trying on a variety of voices to tell the story of a doctor whose cure for a hangover is the cause — peaked at No. 8. Nilsson Schmilsson was ultimately nominated for four Grammys, winning one for Best Male Pop Vocal Performance ("Without You" again). By all rights, it should have served as the springboard for a career's worth of ever-greater success.

Sadly, it wasn't to be — and the reasons had as much to do with Nilsson as they did with the vagaries of the record industry. Although 1972's Son of Schmilsson performed respectably, Nilsson started a downhill slide almost as soon as he hit the top — both creatively, in terms of his fondness for dirty jokes and overall drift toward non-commercial pursuits, and personally, as he spiraled into a period of drug and alcohol abuse that coincided with his pal John Lennon's infamous lost weekend.

Listen to Harry Nilsson Perform 'Jump Into the Fire'

He and Perry split after Son of Schmilsson, and by the middle of the decade, Nilsson be struggling with divorce, slumping sales, and major damage to his voice, incurred during the sessions for 1974's Lennon-produced Pussy Cats LP. In some ways, he'd never quite recover from any of them.

Soaring toward the spotlight as the '70s started, Nilsson was a commercial afterthought as the decade closed; his final album, 1980's Flash Harry, wasn't even officially issued in the U.S. until 2013. He sadly died of heart failure at the age of 52 in January 1994, a little less than a year after suffering a heart attack — and shortly after finishing the vocal tracks for what was supposed to be a new LP.

Decades later, a good portion of the many highlights from Nilsson's discography remain undiscovered by the public at large — but the mainstream will always have Nilsson Schmilsson, a critical and commercial triumph that marked a turning point as well as a double-edged sword for his career.

While it'll always be his most widely known release, for Nilsson, in some ways, it was just another day at the office. "My earlier stuff had more soul," he shrugged after its release. "Only it was more subtle."

See Harry Nilsson Among the Top 200 '70s Rock Songs

More From Ultimate Classic Rock