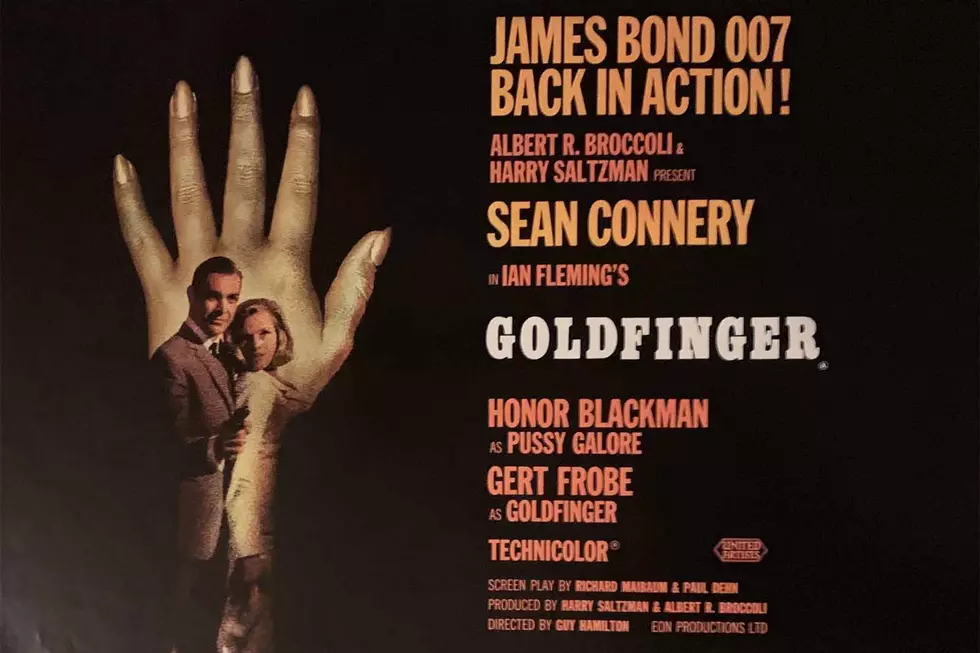

How ‘Goldfinger’ Helped Define the James Bond Film

For many traditionalists, the third James Bond movie, Goldfinger, is the greatest of them all. And indeed, to watch it is to remember the allure, power and strange charm of the Bond series before it fell into the endless replications of the '70s and '80s, or the attempts at psychological profundity found in most recent installments.

The attitude of the movie – which opened on Sept. 18, 1964 – is established in the opening, when James Bond (played by Sean Connery) swims up to the compound of a South American drug-manufacturing operation wearing a waterfowl on his head as a disguise. He sneaks into a secret, futuristic living area inside of what looks like a massive chemical tank, sticks some explosives and a timer onto drums of flammable liquid helpfully stored there, sneaks out again and strips off his wetsuit to reveal that he's been wearing a white tuxedo beneath it.

He pulls a red carnation from somewhere, sticks it in his lapel and goes into a nightclub adjacent to the compound. There, he meets a contact to whom he remarks that at least now the drug kingpin whose compound it is "won't be using heroin-flavored bananas to finance revolutions."

When the explosives he set go off, people panic and his contact suggests that Bond decamp. But he has business to take care of first.

That business is, of course, a woman. As Bond is seducing her, she asks why he always wears a gun, and he remarks, with the faintest of smirks, that it's because he has "a slight inferiority complex." Then a colleague of the woman appears from his hiding place to try to kill Bond, who handily subdues both woman and colleague, drops a quip and walks out the door as one of the greatest of the Bond-stylized credit sequences begins.

From there, the film moves through a dizzying array of scenes, many of which would establish tropes the series would follow forever after.

Goldfinger is the first Bond film to feature an action sequence before the credits which isn't directly related to the main action of the film, and the first in which Bond engages in the hallowed ritual of visiting Q Branch to pick up the gadgets that will allow him to escape what Mike Meyers' Dr. Evil, in Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery, called an "easily escapable situation involving an overly elaborate and exotic death."

Watch 'Goldfinger' Trailer

This is also the first Bond film to feature a villain with a powerful henchman of peculiar talents. In this case the villain is Auric Goldfinger (Gert Frobe), who, as both his names attest, is obsessed with gold. His henchman is Oddjob (Harold Sakata), whose signature weapon is a bowler hat with blades installed beneath the brim that can be thrown to cut off the head of a marble sculpture 30 yards away.

Finally, Goldfinger is the first of the series to give Bond's primary love interest a cheeky name, and it would become the yardstick by which all future Bond Girl's names would be measured: Pussy Galore (Honor Blackman).

Goldfinger succeeds because it does not take itself too seriously. It's aided immeasurably by the presence of Connery; his reaction to hearing Galore's name – a sly smile followed by saying, "I must be dreaming" – is one of the series' best laughs. Like the question of which Bond movie is the greatest, the debates over which actor makes the greatest Bond are labyrinthine. In addition to his gorgeous mug, Connery brings to the role a wonderful satirical edge that, as goofy as it is, never undercuts the proceedings in any way.

It's as if Connery is distantly amused by the fact that his character knows the way to get every woman in bed and has at the tip of his tongue his precise preference for every alcoholic drink imaginable. In addition to ordering his martini "shaken and not stirred" (Goldfinger is the first film where Bond utters the line), he asks for his mint julep with "sour mash and not too sweet, please," and identifies not only the year of a brandy he drinks, but the reason for its indifferent quality.

Similarly, Connery's Bond seems almost entertained when people shoot at him, and no more than befuddled when Goldfinger has him strapped to a table and ready to be bisected by a industrial-strength laser. He delivers pronouncements on the deaths of bad guys with a faint touch of self-regarding pride, as if both the line and the judgment are too good to keep to himself: "Shocking," he murmurs after the death of a man he's electrocuted, or "He had a pressing engagement" after a man is crushed inside a car and "He blew a fuse," after he electrocutes Oddjob.

Contemporary viewers may be put off by, among other things, the film's approach to race and gender. Oddjob does not seem to be able to speak and is only given grunts as dialogue. Herbert "Bert" Kwouk, the wonderful British actor who was mostly relegated to playing various Asian caricatures – including Kato in the Peter Sellers Pink Panther series – makes an appearance here as the leader of a group of nefarious Asians. And the scene in a horse stall when Bond forces himself on Pussy Galore, who struggles against him at first and then seems overcome by the power of his kissing, reads somewhat differently today than it presumably did when the movie was released.

Perhaps it does no good to say that things were different back then. But it also seems fair to note that alongside these depictions there's a great deal of Goldfinger that's still fresh and entertaining. Watching it now, one understands how it helped give birth to a franchise that, all these years and movies later, is still going strong.

James Bond Movies Ranked Worst to Best

More From Ultimate Classic Rock