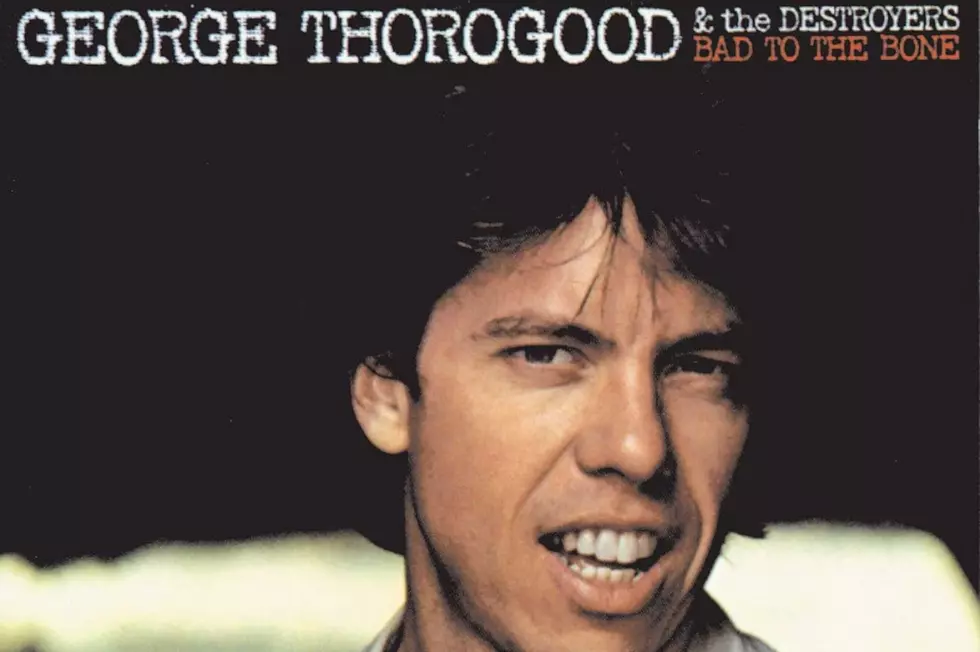

George Thorogood’s Acoustic Adventures: ‘I Kept Breaking Strings All the Time’

George Thorogood has been churning out loud, brash, junkyard-dog rock 'n' roll for more than 40 years. Backed by his longtime band, the Destroyers, his deep love for blues music has been an important part of his records' foundations.

Songs by blues legends like Elmore James and Robert Johnson were anchors as far back as the band's 1977 self-titled debut. Thorogood's latest album, Party of One, marks his first solo blues record. Largely acoustic-based, the LP has an intimate feel, with the artist accompanying himself on a various instruments, including slide guitar, Dobro and harmonica. “It was something I’d been thinking about and every now and then," Thorogood tells Ultimate Classic Rock. “[The record company] would say, ‘You know, we still haven’t forgotten about an acoustic record.’ I’d bring it up or they would bring it up. We’d say, ‘We’ll get around to doing that someday.”

But don't expect to see Thorogood -- who's now on tour with the Destroyers -- on the road by himself. “It won’t happen at all -- ever,” he laughs. “I’m not hired to do that. I’m hired to bring a rock ensemble. That’s what people want.”

I’m here in Cleveland, so it was pretty great to read that local blues legend Robert Lockwood Jr. is one of the people who helped you in your formative years.

He was a very encouraging individual. He did an engagement at a club I had previously worked at [where] I opened for Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. But then I stayed for a while and they would let me play all of the breaks, like when Lockwood came to town. He was quite a unique individual.

The album notes talk about how you started out as a street musician. You probably could have never imagined at that point that you’d eventually find your place doing what you’ve done for over 40 years now. It’s kind of cool the way this record brings things full circle for you.

We had been planning it for a long time. I was all ready to do it then back in ‘73, but I wasn’t with a record label. I got encouragement from Lockwood and others to pick up an electric guitar and go that direction, which I’d kind of been thinking about anyway. I saw Hound Dog Taylor and that did it. That pushed me over the line. That said, “Well, if you’re going to make a statement in this business, you’re going to have to get off that acoustic guitar. Playing with the electric guitar and a bass player and a drummer, that just felt more natural to me. But in the back of my head, I was always thinking, “Someday, I want to get around to making this solo acoustic record, hopefully with Rounder,” so here it is.

In theory, some folks might think that this would be an easier record to make. But from what I know, that’s not the case. There’s a different intensity and feel and approach going from electric to acoustic.

First of all, recording isn’t easy for anybody. It’s just it’s harder for some people. I’m not crazy about being in the studio to begin with and doing it alone, it’s not really my bag. Someone like John Hammond or Taj Mahal or Joni Mitchell, they were accustomed to performing alone and playing alone. I’m not. When I used to play in the clubs, I’d go out and play two or three songs alone and then a band would come on. But finding the material was not easy. It took me a couple of years, actually, to do it. I’d record for about a week and then I’d stop. I’d record a couple of things on the road, and then go home and then go back on the road with the band and go back in the studio. So it took a while to piece this thing together, little by little. Again, I’m not a solo artist. I play in a rock band.

It doesn’t seem like you could have made this kind of record with a band. You could have recorded these songs with a band, but these are definitely songs that needed to be recorded alone.

You have to understand that the artists that I picked that material from, Robert Johnson, was a solo artist. Sonny and Brownie were an acoustic act. John Hammond was a solo artist. Bob Dylan, when he started, was a solo artist. So was John Lee Hooker. The blues originally came from people who played alone. So I was pretty much following the footsteps of bluesmen who preceded me by 30 years. People like Skip James and Robert Johnson and Brownie McGhee, John Lee Hooker, they all played solo. They all played acoustic. Robert Johnson was playing with a band just before he died. Supposedly, rumor has it, he was playing with a bass player and a drummer, fooling around with jazz. So the original blues people, when they were playing, yeah, they played acoustic, then when they moved to the big cities, they want to make a living. The music had to be louder and faster. So they got a bass player and a drummer. I was the same way -- I kept breaking strings all of the time and then I put a pickup in my guitar and that wasn’t enough. I got a guy who played second guitar with me and then I said, “Well, we might as well just get a drummer and go all of the way.” It was a quick evolution for me. What happened to me in the ‘70s was not unlike what happened to other blues artists in the ‘30s and ‘40s.

Listen to George Thorogood's 'Soft Spot'

This album -- songs like “Soft Spot,” in particular -- recalls that time when the records you were getting, you could tell they had minimal access to gear. They had enough to capture the performance and not much more. For a lot of those records, that’s all you needed -- the bare-bones ability to capture the song. A lot of times, it was that, combined with the natural ambiance that was there in the room and the raw honesty of the performance, that made it all work.

All of those artists had an advantage on me because they had no experience playing with rock bands. I mean, I played in front of 80 thousand people opening for the Rolling Stones, you know? That’s not like a solo acoustic act -- you’ve got to have a heavy rock act to do that. They hadn’t even invented electric guitars yet, practically. When they were doing it, that was the only world they knew, so they were the masters of it. I’d come down to your radio station and play one or two songs on acoustic guitar and then it’s back to the rock party.

How did some of the personal connections you had with some of these artists over the years tie into the song selection process?

It’s all difficult, whether it’s a friend of yours or not. I’ve been recording Hooker’s music for years, long before this project came up, when he was still alive. He appreciated that. He was financially compensated for it and appreciated that and let me know it. That was the bonding of our friendship. It weighed heavy on me when I did it, because he had passed away. That was something I thought about. The stories I told about John Lee Hooker in the studio took up more time than it did playing the songs. I had a tough time getting through John Lee’s material, because we were close at one time. So that’s the only part of it that made it difficult. They would say, “Those are great stories, but George, we’ve got to record the song! C’mon, let’s keep going here!”

Well, that was part of it, knowing the long connection that you’ve had with some of these folks. You look back at “One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer,” you wrap in part of one of Hooker's songs with that. So you go back a long, long way with some of these people. Unlike some people who would do a record like this, you’ve got a lot attached to the songs.

Brownie McGhee’s song was very personal. I remember him doing that when we performed. That struck a little closer to home. John Hammond and I go way back. He was a big influence on me. There were a couple of things in there that were a little closer. I did do a few shows with Howlin’ Wolf, opening for him. I was a big huge fan of Howlin’ Wolf. Not unlike people like Hank Williams and Johnny Cash, people like that. But with Brownie and with that song in particular and John Hammond, that was a little closer. I was just fortunate I was able to pull it off, because they meant a lot to me, when I was first getting started.

When you look back at the experience of playing gigs with folks like that when you were coming up, what do you think you took away from the experience of working with people like that who had been doing it in some cases for decades?

First of all, to start anything, any business you start, regardless of how good you are at it, you have to have confidence in yourself that you can do it. You don’t think that you can do it, you know that you can do it and that has to be first. No matter what you do. I showed up on the scene and I was in that thought process to begin with. With Sonny and Brownie and Lockwood and Hound Dog Taylor, they pushed my confidence to a whole different level that I didn’t even know was there. They were saying, “You’re good enough to come here and open for us and play here and get a hundred dollars a week, but we think you’re much, much bigger than that. Get an electric guitar.” They were right. So they pushed my confidence in a whole different area, which I appreciated, especially Sonny Terry and Hound Dog and Robert Lockwood Jr.-- he wouldn’t leave me alone, he was very serious about me for some reason. He wasn’t joking around -- he was a very serious man anyway and there was no joking around. He said it as naturally as he said his own name, he said, “You know, don’t be fooling around. Don’t be shy about what you’re doing, because it’s not working with me.” That’s how Lockwood would put it -- he didn’t buy it. So they pushed George Thorogood’s confidence level to a different level.

Listen to George Thorogood's 'Bad News'

It was interesting listening to this stuff. I can really hear what sounds like from your side, a conscious effort to capture the essence of the original well-known vocals and vocal mannerisms that people would remember from the original recordings. A song like “Bad News” for example, Johnny Cash brought a lot to that song, just by being Johnny Cash, and it seems like a good amount of important elements like that would have been on your mind as you’re recording this material.

I also thought about the fact that I was doing it for Rounder Records. They have very high standards with that company. They had won awards. People like Robert Plant have done tremendous record sales with them. Alison Krauss and Steve Martin, they’ve done great work, and they have a high standard of what you’d better deliver. So that was on my mind too. More than just doing justice to the material I was doing. And then my own work ethic is to do the best job that you can with the energy that you have right at the moment. All of those elements were intertwined at the same time. But I’m still a company man, I had to produce a good product for Rounder. I was working for them.

It was interesting hearing the performance of “One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer” from the radio program Rockline that’s on this record. Here’s a performance that comes from nearly 20 years ago. Sonically, it really fits in well. If somebody told you that this was recorded at the same time as the rest of the record, you would believe that. Did you have this sitting in your archives?

I actually heard it on the radio and I didn’t know who it was. I thought it was somebody else playing. [Laughs] It sounded so good that I thought it was somebody else. I thought, “Man, somebody’s really smokin’ with that acoustic guitar” and I was informed that it was me. I said, “Holy smokes, well, there’s one cut that we can use. I don’t have to re-cut that one.” It took a while to track it down, but we finally got it.

I know there’s been rumblings about another album with the band. Have you started writing yet? What’s the plan there?

You never close that door completely. You always keep your options open. But no, at the moment, I’m not writing any material. I’m touring and promoting this record like crazy, so I really don’t have the time for going that way. But who knows? You never know.

What’s a good memory from your time touring with the Stones?

We had an engagement in Holland during that run, and we played on Friday and we had off on Saturday. We played again on Sunday and I think the Saturday, we had a club date where Bobby Keys and Ian Stewart joined us. Just as we were finishing up, Mick Jagger came into the club and got up and sang a couple of songs with us. That was amazing, really. Here’s a man with not a lot of time on his hands. He’s arguably the highest rock figure that there is, it’s his night off and he’s on tour in Europe. He took time out from his schedule to come and see us play. And then to stick around and actually get up and sing, and he invited our drummer, Jeff Simon, and I, to go to a nightclub and chat. It was a wonderful experience, and he didn’t have to do that. I got to meet the Rolling Stones before I ever saw them play. Not many people can say that. The first thing one of the Rolling Stones said to me was, “May I have your autograph?” He didn’t even say “Hello or good morning, I’m Charlie Watts.” He had our record and said, “George, excuse me, may I have your autograph?” That wasn’t even the tour -- that was the first date I played with them, not knowing if I was going to get any more dates. The thing in Holland came much later.

You mentioned Ian Stewart, and you’ve played with some incredible folks across the years. How did he end up playing with you?

He had come to see us play in London once, and I didn’t get a chance to meet him. Jeff Simon did, and they chatted. It was about ‘78 or ‘79, and he showed up [later] at a Stones gig, and I did the song “The Sky Is Crying,” and he liked it very much. He went to Jeff and he said, “Would George mind if I sat in on that song?” I said, “Of course not, I wouldn’t mind having Ian Stewart sit in." Besides I’ve never played in front of 100,000 people before, I was lucky to play in front of 1,000, not 100,000 people, so we needed all of the instrumentation we could get up there to fill out the sound. He played on that one song and then after that, he played every show with us. He started playing with us regularly in California, and every show that we did from then on out, he was there. So when the tour was over, we signed a deal with EMI America [in 1981]. Ian said, “Could I record with you?” I said, “Well, sure you can!” He came to the studio in Boston and did the record and then asked, “What are your plans?” I said, “Well, Ian, we’re going to go play in Canada in the late summer,” and he said, “Well, can I go on that.” I said, “Yes, you can!” He was really quite a wonderful guy. I think we were kind of a throwback to the old Rolling Stones in ‘62 and ‘63 when they were first getting together and they were doing all blues covers before they produced original rock 'n' roll hits. Ian was still very much into that -- he liked our blues boogie thing. I was just on the cusp of starting to write originals. We still had a bag of non-originals that we did that he enjoyed. He didn’t enjoy my volume too much! [Laughs] I guess I played a little loud, but I said, “You play with Keith Richards and Ron Wood, what are you talking about, volume? Don’t talk to me about volume!”

Masterpieces: The Very Best Albums From More Than 100 Classic Rock Acts

More From Ultimate Classic Rock