40 Years Ago: Gentle Giant Crack the Charts With Funky ‘Free Hand’

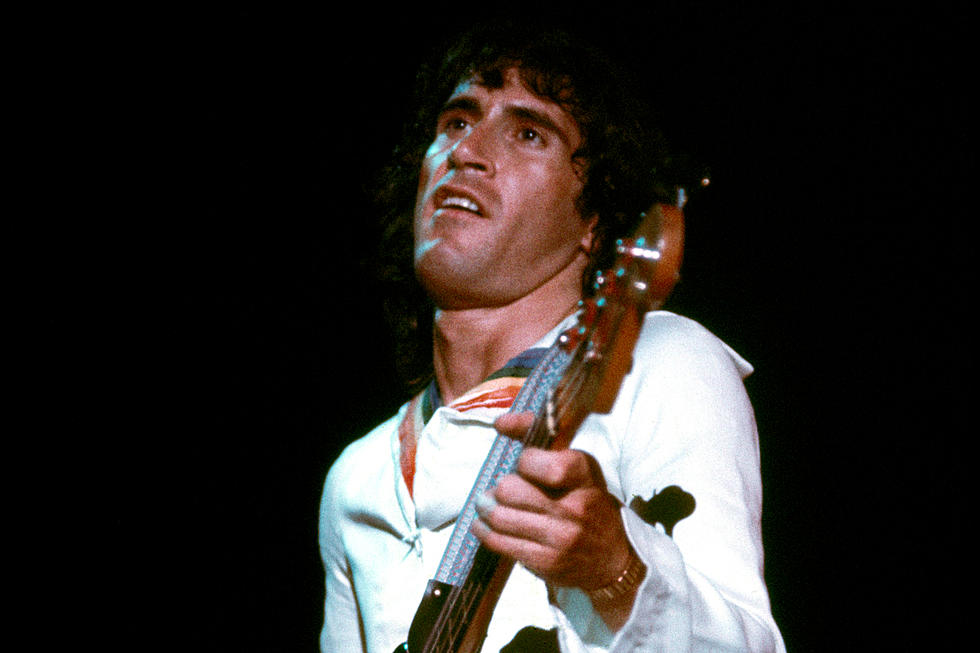

Even at their most accessible, Gentle Giant never lost their eccentric identity. The British band's seventh LP, Free Hand, proved to be their commercial apex, crawling to No. 48 on the Billboard chart with funky, riff-heavy attacks like "Just the Same." But by emphasizing more of the rock in their singular prog-rock, the quintet also reached a creative pinnacle.

Free Hand was released in July 1975, but its songs remain untethered to any era. Giant-produced, with crystal engineering by Gary Martin, the LP bristles with rhythmic energy and melodic clarity – less dissonant and self-consciously experimental than the previous year's The Power and the Glory. Part of that focus came from touring with rock heroes Jethro Tull and signing with their label, Chrysalis Records.

"We really liked [Tull] as a band", keyboardist Kerry Minnear noted in Free Hand's reissue liner notes, "and basically they were about the only real friends we made on the road. It was through this relationship, and getting to know Terry, that the eventual move to Chrysalis came about."

"[Ellis] made us work, and the whole buzz of playing live came back," added frontman Derek Shulman. "We started talking again, enthusing as we had done before [1972's] Octopus."

The Chrysalis association helped the band's promotional pull – the songs took care of the rest. Giant had always displayed an unexpected funk finesse, particularly with the dexterity of bassist Ray Shulman and drummer John Weathers. But Free Hand took their rhythmic edge to a new level: Closer "Mobile" is a dizzying trek through violin blasts and pogoing drums, while the title-track driven cruises on Minnear's honking clavinet.

Giant's experimental edge hadn't softened: see the knotty vocal counterpoint of "On Reflection," medieval-psychedelic instrumental "Talybont" and the intricate balance of jazz and folk on "His Last Voyage."

But the album's signature track – the one that epitomizes the album's broader appeal – is opener "Just the Same," a hard-hitting anthem propelled by squiggling synth blasts and flurries of alto sax.

"[The song] did very well," Derek Shulman recalled in an interview with Vintage Rock. "We were kind of a popular group actually in certain places, but then we saw radio and the acceptance of hit singles when FM radio became AOR. Bands who would sometimes tour with us as backup bands became bigger because of a big hit. I think there was an element of us chasing a hit. And as Ray said, in retrospect, to look back at it, it was a dumb thing to do, but we did it. There were elements of envy, I will say that."

"We saw Genesis and Yes cross over to the mass audience, and there were certain territories where we did play stadiums, like in Canada and parts of Europe. But we didn't have a mass audience everywhere," Ray Shulman added. "There was also – certainly in the latter part of the '70s – a big cultural shift in this country, in Britain, of punk music. It was a bit more cultural because of what was going on in Britain. I think we made an album where there were three days we used a generator because there no electricity. And you could see in just that, the kind of complicated music and lyrical themes – they weren't relevant any more in this country. Obviously things were changing, so you had to kind of change yourself. Or you give up."

Gentle Giant's quest for commercial viability led to diminished returns later in the decade, as the band fizzled out during the Great Punk Boom. But for a brief, splendid moment, the quintet's signature psychosis was tailor-made for the masses.

See the Top 100 Albums of the '70s

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's Worst Snubs

More From Ultimate Classic Rock