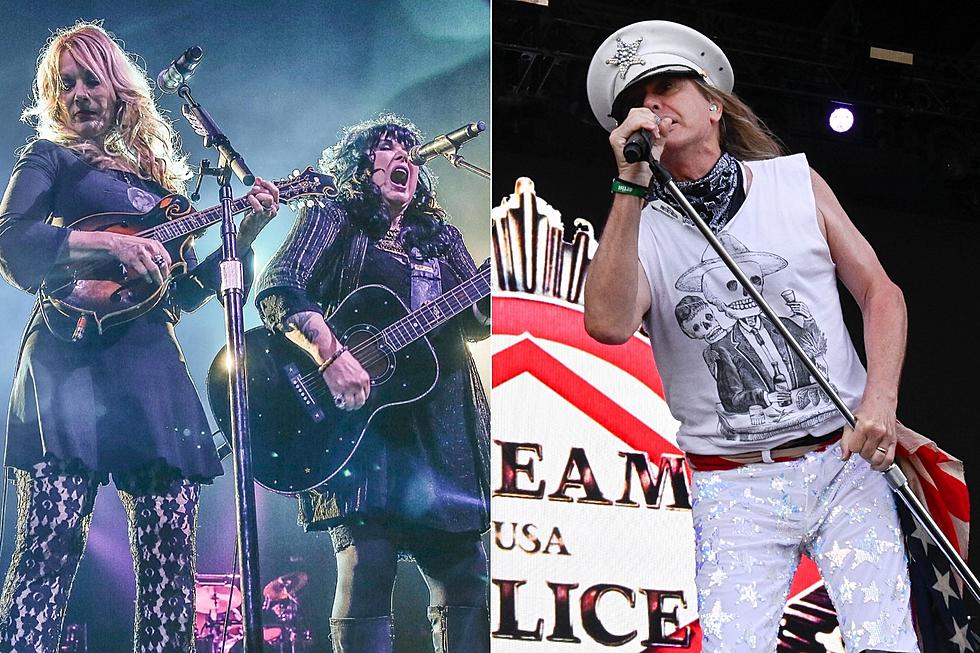

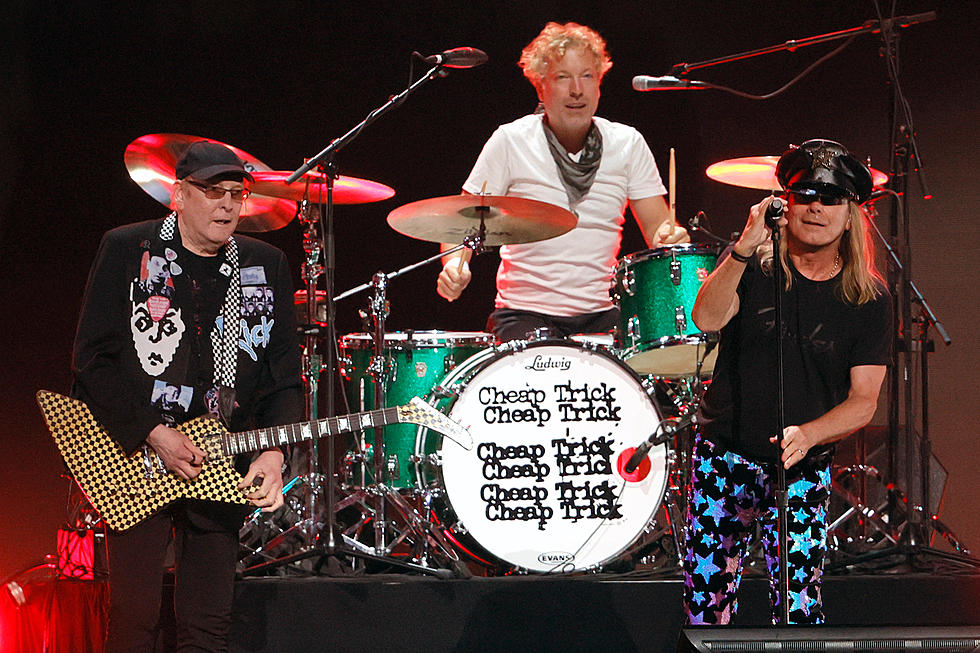

How Cheap Trick Explored New Sounds With ‘I Want You to Want Me’

Cheap Trick's "I Want You to Want Me" has become a classic-rock staple since it was first released as part of In Color in 1977.

But it was hardly a sure thing at the time. Producer Tom Werman had an interesting vision for the song. In his head, he heard it as a "dancehall tune," something which comes through in the bouncy feel of the final recording. The jaunty piano from Jai Winding, one of the guests on the sessions for "I Want You to Want Me," adds a bit of a saloon vibe to it, especially when he takes a solo at the midway point.

By the time they took it to the stage, as immortalized on 1978's classic Cheap Trick at Budokan, their treatment further boosted the energy levels and cranked up the guitar, while still maintaining the core feeling of the original recording.

In an exclusive excerpt from This Band Has No Past: How Cheap Trick Became Cheap Trick, Brian J. Kramp offers a look inside the recording process for "I Want You to Want Me" with memories from Werman, Winding and others who were part of helping to bring the song to life.

After laying waste to the Whisky, Cheap Trick hunkered down at Cherokee Studios in Hollywood, where they had booked three weeks to record their second album. Issues arose immediately. Apparently, improvements were being made to the facility. The band would be in the middle of a take when the hammering or drilling would begin. People would wander in and out while they were recording, including an unwelcome cameo from Art Garfunkel. The unprofessional atmosphere proved untenable, and with just four basic tracks in the can, the decision was made to pull the plug and regroup elsewhere. They landed at Kendun Recorders in Burbank, where the process went much more smoothly.

Tom Werman: We just jumped from song to song to song. We got stuff done so quickly. I was spoiled by them. The favorite band I ever produced, far and away. Just a great, productive, funny, smart group. Everybody in Cheap Trick was brilliant. Robin Zander was the best vocalist I ever worked with, Bun E. Carlos was the best drummer, and Tom Petersson was the best bass player. They were great!

As great as they were, Werman was feeling the pressure to produce a more commercial record—one that would sell more copies than the first one had. As Bun E. Carlos remembered for Classic Rock Revisited, "The basic blowback from the label we got was, Look, the first record didn’t get on the radio. This guy’s gonna get you on the radio. And that’s why we’re gonna tame ya down a little bit." Tom Werman elaborated on his intentions for Trouser Press: "I wanted to make the band more palatable; more, I hate to use the word, commercially acceptable, without forcing them to compromise their artistic integrity."

"Werman wanted us to be like the Who," said Rick Nielsen.

‘More like the Guess Who,’ said Petersson.

Werman explained his approach to Greg Brodsky: whereas Jack Douglas had "captured the band pretty much as they were," Werman "used the studio technology to a greater degree," including "more instruments and more layered guitars and things" so "it came out with more space."

"I think you could hear everything a little better than on the first LP," Werman added. "There are ways to treat buzzing guitars in a studio so that they don’t take up as much frequency range and don’t compete with the other instruments."

Tom Werman: We did some overdubs at Westlake Audio because I remember that’s where we put the piano on "I Want You To Want Me."

Werman heard the song as a "dancehall tune." He rented a tack piano and brought in a session guy named Jai Winding.

Jai Winding: What I remember about recording the piano was Tom Werman was adamant about not having any overdubs stick out, especially from a session musician keyboard player. Tom wanted the focus to be just on the band and not having their Midwestern rock band cred tainted by the addition of session players. So I tucked the piano part tightly into Rick’s rhythm guitar part and Tom’s pulsing quarter note bass part with no extra movement or notes to make the listener wonder if there was a piano part. Feathering the piano just far enough behind the rhythm guitar, with my left hand doubling Tom’s driving bass line.

Werman enlisted the services of another session guy, the legendary Jay Graydon, to lay down some genre-appropriate lead guitar on "I Want You To Want Me."

Listen to Cheap Trick's 'I Want You to Want Me'

Tom Werman: Rick wasn’t putting the song across the way I heard it, the way I thought it should be, and I wanted a more club, jazz, thirties sound.

Nielsen claimed that he "wasn’t there when it was going on. It was not like any lacking on my part." Graydon described what he did for the song as "wire choir."

Jay Graydon: Harmonizing guitar parts. Play a single line and then work out the harmony to it. Sometimes one harmony part, sometimes two. That’s a big part of the studio musician’s job. I’m supposed to come up with a memorable hook. If the producer wants me to play a line in the beginning of the song, my job is to come up with a simple, memorable lick.

"I Want You To Want Me" was the only time Graydon ever "ghosted" on a record—otherwise, he was always credited. How did Nielsen feel about having a stunt guitarist? He told Ultimate Guitar that he "told them what I was looking for, and yet, it really got taken away from what I was thinking and had in mind."

Tom Werman: He probably didn’t enjoy having that done, but he didn’t complain at the time. He was very agreeable to everything in the studio.

Werman’s approach to the song certainly represented a departure for the band, yet it made sense as an interpretation, given the inherent vibe of the piece. Considering the misgivings that the members of Cheap Trick have expressed about the direction that was taken with the song in hindsight, Werman harkens back to a specific moment in the studio when he felt like he was given the thumbs up.

Tom Werman: They were on the couch, we were doing an overdub, and I turned to them and I asked them a question. "Do you like this, or should we do that?" And [Rick] said, "You’re the producer." And I remember that. And I thought that was, You’re doing a good job, just keep going, I’m cool.

Robin Zander has been more forgiving of the song’s "real boppy" production. "I didn’t hate it," he told Sentinel Daily. "It just wasn’t us." It might have seemed, at the time, as if all was for naught, as the single did not become a hit. And yet, Cheap Trick undeniably assimilated elements of the Werman arrangement into the way they performed "I Want You To Want Me" moving forward, including on Cheap Trick at Budokan.

Tom Werman: It was a live version of the studio version.

The new approach imbued the song with a swing and a bounce. Prior to In Color, Cheap Trick’s performances of "I Want You To Want Me" could be choppy, even clumsy; "Yardbirds-ish,’ is how Zander described it. Yet the ditty clearly had potential. Robin McBride and Jack Douglas both heard it. Werman made it what it kind of wanted to be, a genre piece or a novelty tune. All I’m saying is, it was not an unjustified approach.

In 1978, Rick Nielsen told Nuggets that "working with Tom’s been good, he’s easy to work with." Werman felt the same. "We had a really good time in the studio," he told Chuck Harrell. "The vibes were great, there was a lot of laughter." As for the net result, Nielsen conceded to Ultimate Guitar that Werman "did a good job and the record got released and the songs are good," then added a caveat: "but it’s like he made a heavy band sound wimpy." Werman begged to differ. "I never mixed a record without running it past the group," he insisted. "I always gave it to the group for approval. You know, it’s just common courtesy."

"In Color, no matter what you thought of it, was a time and place, and that’s where we were," Zander reflected for The Jeremy White Podcast. "And we allowed all that to happen and some people like that record best of all of our records."

Top 100 Live Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock