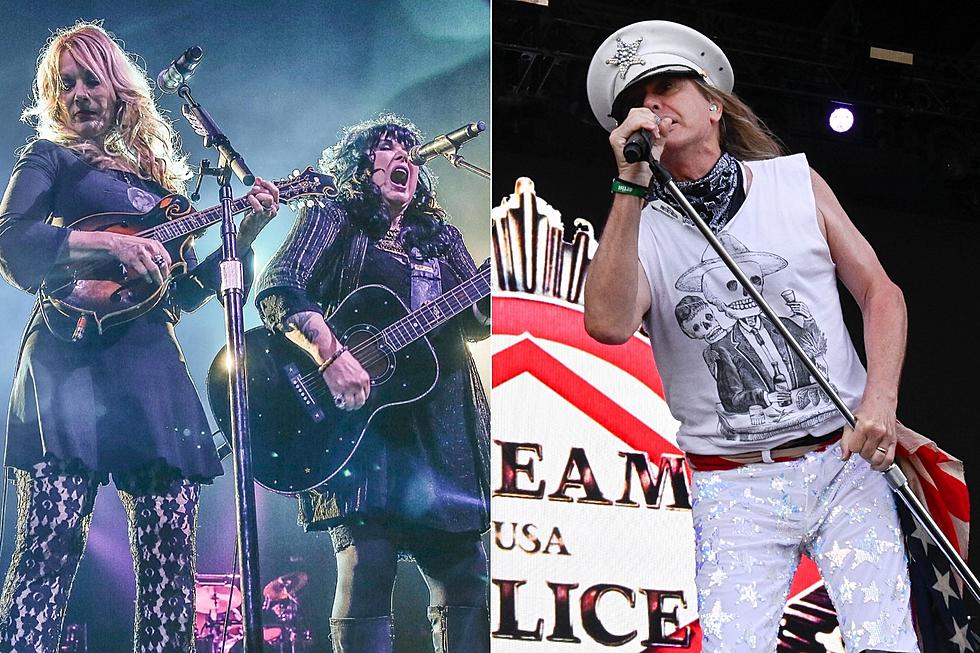

35 Years Ago: Cheap Trick Continue Their Identity Crisis on ‘Next Position Please’

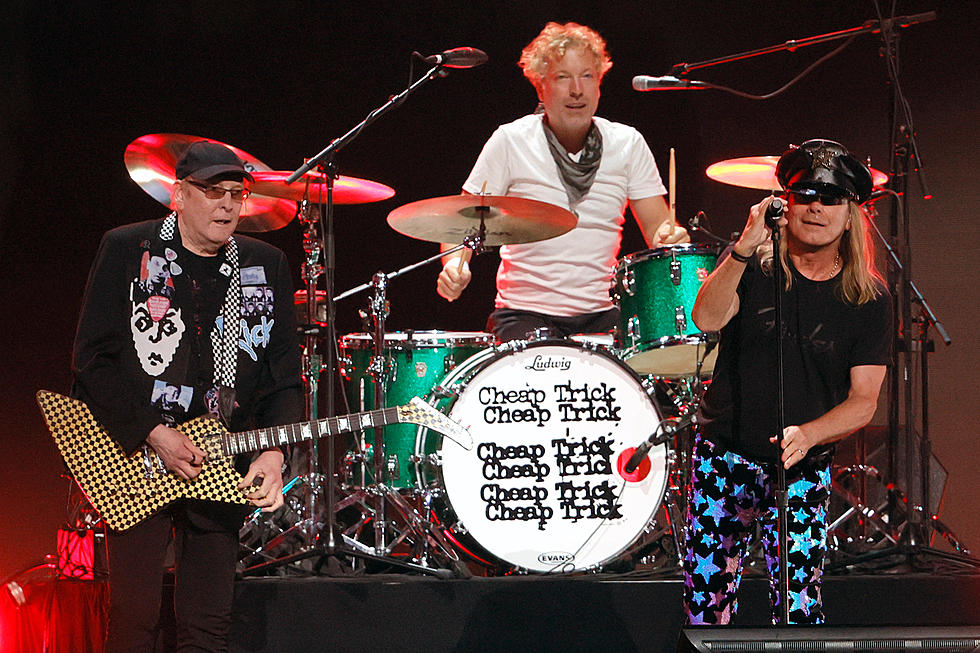

A little over a year after scoring a Top 40 hit with their sixth studio album, 1982's One on One, Cheap Trick returned on Aug. 15, 1983 with the follow-up, Next Position Please.

After enjoying multiplatinum success during the '70s with a series of records produced by Tom Werman, the band entered a period of creative flux in the '80s, both in terms of personnel -- original bassist Tom Petersson departed in 1980 -- and in terms of production. Position found them working with Todd Rundgren, their fourth producer in as many albums: Roy Thomas Baker helmed One on One, George Martin took the reins for 1980's All Shook Up, and Werman was behind the boards for 1979's Dream Police.

It all added up to a bit of an identity crisis for the band, and a series of records that moved between more layered efforts like All Shook Up and brasher, more direct sides like One on One. Next Position Please fell somewhere in the middle; as drummer Bun E. Carlos recalled in a later interview, "We went up to Woodstock and recorded at [Rundgren's] little A-Frame studio. Yeah, I brought my stage kit, and we put some mikes on it. We didn't want it all jazzed up like Roy Thomas Baker did, all this noise gate crap. Todd wasn't into that either, so that was good. The only thing that is kind of dated on that record is the guitar sounds. Rick [Nielsen] was using a Rockman or whatever it was called, and that's on every song. But otherwise, the album still sounds really good these days. There weren't all these gimmicks on it and all these effects."

Four years removed from the massive success of Cheap Trick at Budokan, the band found itself struggling to stay in the spotlight -- something that obviously rankled vocalist Robin Zander during an interview conducted during the Next Position Please sessions. "Our albums have always done consistently well since we put out Live at Budokan, but for some reason we’re always being asked why our last record didn’t do so well," he complained, before going on to delineate the differences between Position and its predecessors.

"The record has more of a general pop sound," he explained. "We paid more attention to the actual songs than to specific sounds, meaning we went for a pretty basic approach without the layering of guitar and vocal tracks." In Zander's eyes, working with Rundgren made a huge difference: "Not only is he a musician himself but he also writes and produces. It gives him a much better rapport with the band because he understands all the inner workings involved, something that a producer might never understand."

Unfortunately, all that rapport didn't translate to increased faith on the part of the band's label, Epic Records. Setting the tone for a decade of insisting that the group record outside material, Epic demanded a cover song ("Dancing the Night Away," originally recorded by the Motors) which Rundgren refused to produce, forcing the involvement of One on One engineer Ian Taylor. (Somewhat ironically, Rundgren wrote the other non-Trick original on the record, "Heaven's Falling.")

Ultimately, Next Position Please didn't do much to rekindle Cheap Trick's commercial fortunes, stalling out at No. 132 on the Billboard 200, and neither "Dancing the Night Away" nor the follow-up single "I Can't Take It" had much of an impact on the Top 40. When the band returned to the studio for their next album, Standing on the Edge, they'd do so with the assistance of "song doctor" Mark Radice -- and by the time they returned to commercial success with 1988's Lap of Luxury, they were relying heavily on outside material.

See Cheap Trick and Other Rockers in the Top 100 Albums of the '70s

More From Ultimate Classic Rock