When Bob Marley’s Family Headed to Vaults for ‘Confrontation’

Bob Marley’s death in 1981 at age 36 did not hamper his influence on politics and culture, whether in his native Jamaica, in the African nations he so dearly loved or in the areas of Europe and the United States where his music had taken hold.

In fact, in his absence, his influence might have expanded. Although Marley was no longer present to speak himself, he had left a decade’s worth of music to carry on his message of justice, unity, love and deference to a higher power.

In the late ‘70s, he conceived a trilogy of albums whose purpose was broad but conceptually simple — to unite Third World nations and bring about revolutionary change through music, guided by the hand of that higher power. It began with 1979’s Survival, an incendiary call to arms and call for unity of all African nations.

Militant in its message, the album was, in the words of The Daily Star, “an answer to the critics, who found his previous album Kaya ... a laid-back, substance-soaked work that sidetracks the urgency of his message.” Timothy White (author of the definitive Marley biography, Catch a Fire: The Life of Bob Marley) called Survival “a laying out of the agenda for the apocalyptic battle between his brethren and Babylon, and it had all the incendiary might of a don't-look-back manifesto.”

Survival was followed by 1980’s Uprising — the last album Marley would release in his lifetime. In Catch a Fire, White called it “an inspirational work, intended to offer support to the assembled multitudes as they hastened to set their spiritual houses in order.”

Listen to Bob Marley's 'Redemption Song'

Its most famous track is the album-closing “Redemption Song,” a song that instructed listeners to “emancipate yourselves from mental slavery / None but ourselves can free our minds” and imploring them also to “help me sing these songs of freedom.”

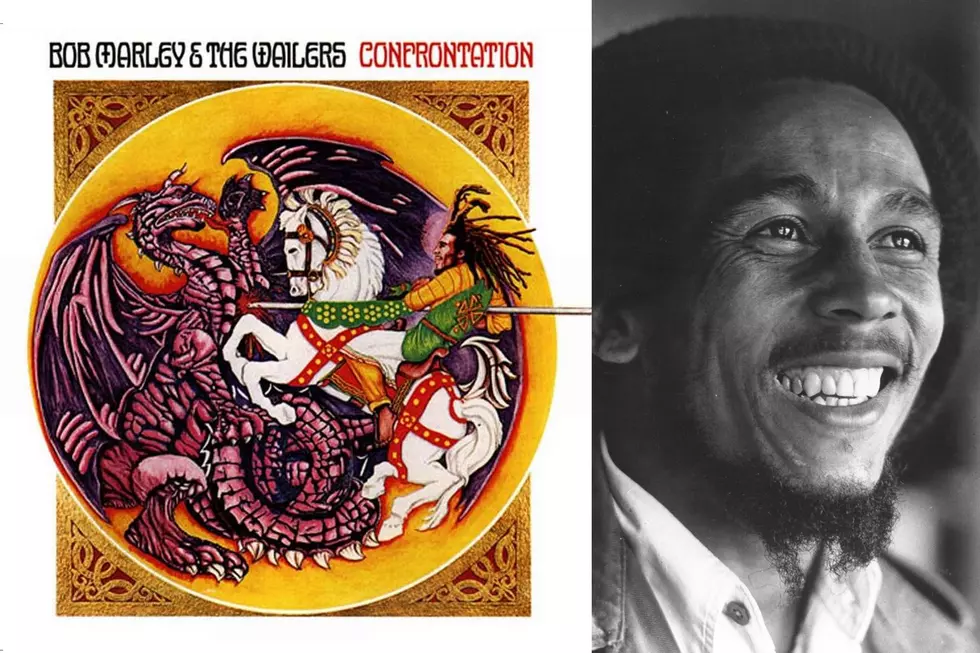

If Survival gathered the tribes and Uprising inspired them to action, Confrontation was intended to herald a battle over the forces of evil in the world. The idea, according to critic Jim DeRogatis, was to “chronicle the battle of the Third World against ‘Babylon,’ the symbol of its oppression.” The assumed end would be victory and a resolution, both without, in the world, and within, as the “soldiers” in the conflict resolved their own internal struggle with evil.

Released on May 23, 1983, the laid-back sound of many key tracks on Confrontation contrasts with the ambition Marley set out for the record, perhaps because he was not present to complete the album (according to Rolling Stone, Marley’s wife Rita and Island Records president Chris Blackwell wound up compiling and finishing it), though maybe it was intentional.

“Like many of Bob's records of the late 1970s," White wrote, “Confrontation contained songs that had reached maturity in an utterly casual creative atmosphere.”

Listen to Bob Marley's 'Jump Nyabinghi'

The record starts with seven chords, repeated three times, which introduce “Chant Down Babylon” — 10 seconds of guitar, drums and organ that could have kicked off any number of soul or R&B records; instead, Marley links those sounds (and, by connection, their traditions) to the reggae that follows.

“Chant Down Babylon” is a call to use music to conquer evil forces and “all their wicked intentions to destroy the human race.” Contrasting that call is the music itself, which is lighter than light, even sprightly.

Similar in tone and message is "Jump Nyabinghi," which finds Marley in one moment singing, “Love to see when ya groove with the rhythm,” before once again calling for his audience to “keep on trodding until Babylon falls.”

Elsewhere, Marley offers comfort to those in the fight who need spiritual sustenance. “I Know” sounds less like a reggae track, and more like an R&B demo, with electronic drums and synth strings supporting a wonderfully fervent vocal from Marley. “Ain’t it good to know now / Jah will be waiting there,” he sings. “... Bring my children from the end of the earth.”

Listen to Bob Marley's 'I Know'

More subdued is “Give Thanks & Praises,” which is equal parts sermon and call to praise the higher being. It’s also one song in which one notices the beauty of the background harmonies provided by the I-Threes, who were added to the track (and virtually all other tracks on the record) after Marley’s death.The voices sound seamless with the rest of the song, and provide it with additional sonic depth.

By far the best-known song on Confrontation is “Buffalo Soldier,” which, thanks to its placement on Marley’s bestselling compilation Legend, has served as the soundtrack countless backyard cookouts and fraternity keggers for a generation or two, but which is anything but a party anthem.

Marley, a history buff, read of the black soldiers of the U.S. Army’s 10th Cavalry regiment, who from 1866 into the 1890s, according to historians, built infrastructure and fought off Cheyenne and Apache tribes to protect white settlers during the westward expansion after the Civil War. Marley connected the regiment’s mission with the slave ships that brought its members’ forebears to the land they protected. “Stolen from Africa, brought to America” he sang, “Fighting on arrival, fighting for survival.”

Though culled from disparate sources and embellished with music and voices after Marley’s demise, Confrontation holds together well as a final statement from reggae’s spokesman and champion. As a whole, it perfectly, if quietly, melds his spiritual and political concerns into a missive to his masses of followers, providing them with strength and comfort as they challenged their oppressors daily.

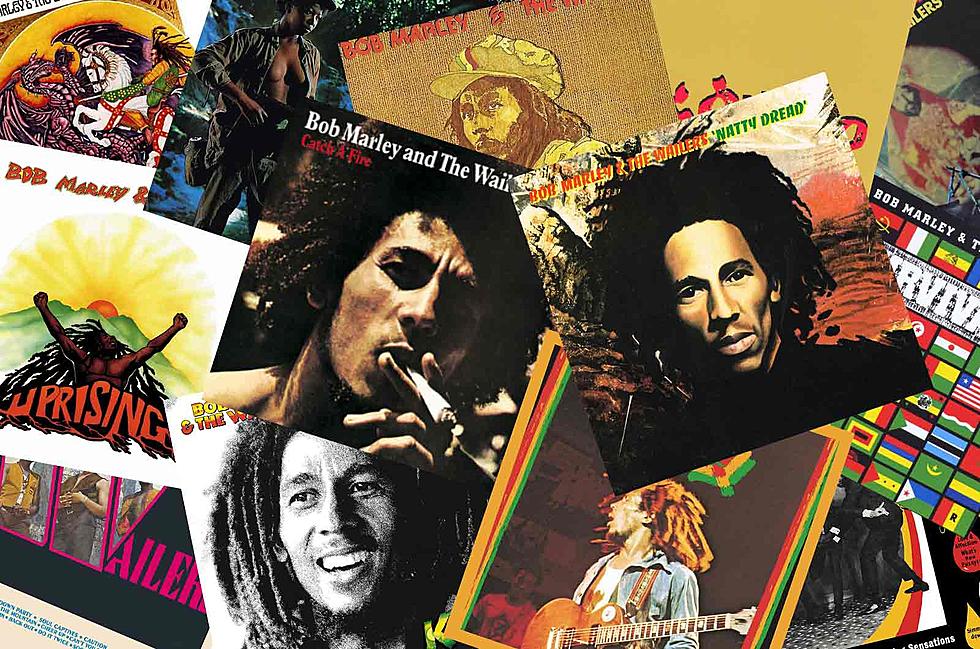

Bob Marley Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock