When Simon and Garfunkel Delivered Their Masterpiece

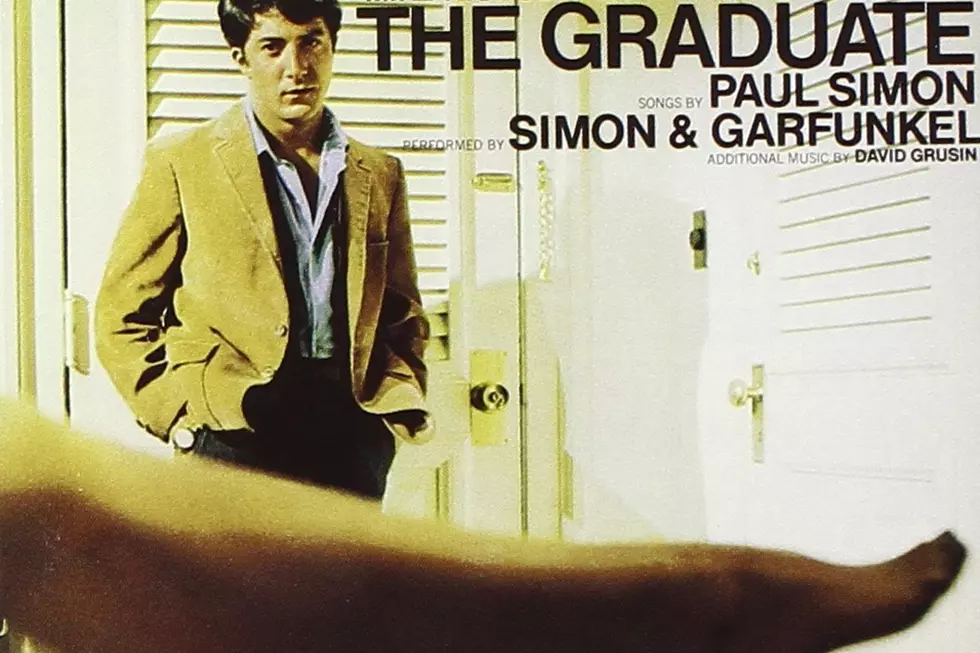

When Neil Young wrote "it's better to burn out than to fade away," he might as well have been talking about Simon & Garfunkel. The duo rode a critical and commercial high as the '60s ended, with a pair of Top 5 albums (1966's Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme and 1968's Bookends) and the chart-topping soundtrack to Mike Nichols' hit 1968 film The Graduate under their belts. Their fifth LP, Bridge Over Troubled Water, would offer their most ambitious – and most fully realized – work. It would also spell the end of their partnership.

For those who knew Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel, the notion of a split probably wouldn't have been difficult to fathom, even at the peak of their success; during their long personal and artistic association, they'd broken up more than once before. But commercially speaking, they were all but infallible when they entered the studio to record Bridge – and in musical terms, they seemed to be just getting started.

Branching out from the pure folk roots of early sides like The Sound of Silence, Simon & Garfunkel had – with the able assistance of engineer/co-producer Roy Halee – started using the studio as an instrument on more recent recordings, and with Bridge Over Troubled Water, they took those efforts to new heights, incorporating everything from home taping experiments ("Cecilia") to the cavernous acoustics of a chapel ("The Boxer").

Released on on Jan. 26, 1970, the album's arrangements were no less eclectic. With a restless Simon charting their musical path, the duo covered wide swaths of ground on Bridge, starting with the gospel-kissed tones of the title track and continuing through Peruvian folk music ("El Condor Pasa"), Latin jazz ("So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright") and a touch of reggae ("Why Don't You Write Me"), and even made time to bring them full circle with a cover of the Everly Brothers' "Bye Bye Love."

It's the title cut and lead-off track that ended up becoming the album's defining hit, however, and for fairly obvious reasons – including a soothing message and arrangement that reminded more than a few listeners of the Beatles' "Let It Be," as well as a soaring lead vocal from Garfunkel. Like the album, the single topped the charts on both sides of the Atlantic, and went on to become a pop standard as well as an enduring focal point for Simon and Garfunkel's separate careers.

"I was very pleased to hear such a rich song intended for me. I always felt he did some of his best writing when it came in the form of a gift. When people get outside of themselves and say, "This is for you," it taps the better part of themselves," Garfunkel told Paul Zollo years later. "And I loved it."

Calling the song "something of a mystery to me," Simon recalled, "Nothing prompted me to write it. I was listening to a lot of gospel quartets, particularly the Swan Silvertones and the Everly Brothers album Songs Our Daddy Taught Us. I was stunned and I thought, 'that’s a lot better than I usually write.'"

Listen to Simon and Garfunkel Perform 'Cecilia'

As Garfunkel noted, Simon offered "Bridge" to him as a gift, but that was just one conciliatory moment during a period in which relations between the two were growing progressively more strained. Particularly problematic -- for Simon, anyway – was Garfunkel's decision to accept a role in Nichols' Graduate follow-up, Catch-22. It was only supposed to be brief, but his filming commitment gradually stretched out over weeks and months, slowing down the recording of the Bridge Over Troubled Water album and frustrating Simon, who channeled his impatience and insecurities into the songs "So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright" and "The Only Living Boy in New York."

In retrospect, however, Garfunkel admitted that his row with Simon over Catch-22 was really just a symptom of a much larger problem. "We weren't having a good time. We weren't enjoying ourselves. We were tired of working together. We wanted a break from each other," he told SongTalk. "We were not getting along particularly well, and there were a lot of conflicts that were unpleasant conflicts. ... I remember thinking, 'When this record's over, I want to rest from Paul Simon.' And I would swear that he was feeling the same thing, like 'I don't want to know from Artie for a year or so.'"

The catch, supposed Garfunkel, was that it ended up being his absence rather than Simon's edict that put the brakes on their work – and so instead of a hiatus, it turned out to be a split. "I was in love with Simon & Garfunkel. I thought we were a neat act. I didn't want to tip that over, I just wanted to take a rest from it," Garfunkel insisted. "And here, with the help of Mike's offer, I wanted to enrich my side of the group with this acting role. Well, Paul couldn't abide by these things. They were evidently threatening. So, in his mind, waiting for Artie is something he couldn't do. Now, I was waiting for Paul to write the tunes all the time, before we'd go in the studio."

Simon admitted, in a talk with Rolling Stone, that "it was very hard work, and it was complex. I think Artie said that he felt that he didn't want to record, and I know I said I felt that if I had to go through these kinds of personality abrasions, I didn't want to continue to do it. We didn't say, 'That's the end.' We didn't know if it was the end or not. But it became apparent by the time the movie was out, and by the time my album was out, that it was over."

In fact, it may have been apparent before that. "On several tracks on Bridge there's no Artie on it at all," Simon continued. "'The Only Living Boy in New York,' he sang a little on the background. 'Baby Driver,' he wasn't there. He was doing Catch-22 in Mexico at that time. It's a Simon and Garfunkel record, but not really. And it became easier to work by separating. On Bridge Over Troubled Water there are many songs where you don't hear Simon and Garfunkel singing together. Because of that, the separation became easier."

The fighting even extended as far as song selection. "There's 11 songs on Bridge Over Troubled Water but there were supposed to be 12. I had written a song called 'Cuba Si, Nixon No.' And Artie didn't want to do it. We even cut the track for it. Artie wouldn't sing on it," Simon protested. "And Artie wanted to do a Bach chorale thing, which I didn't want to do. We were fightin' over which was gonna be the 12th song, and then I said, 'Fuck it, put it out with 11 songs, if that's the way it is.' We were at the end of our energies over that."

Listen to Simon and Garfunkel Perform 'The Boxer'

They never said "that's the end," but in the weeks after Bridge started its long chart reign, they did offer signs that, at the very least, Simon & Garfunkel were headed for a hiatus.

"It may sound strange, but time is running out. You go to do things because once you get a certain point, you've got to ride your energy while you have it," warned Simon after Bridge was released. "As long as you have energy and curiosity and drive, you use it. And I don't know when that will end."

By 1972, when Simon released his self-titled solo LP, it seemed pretty clear he and Garfunkel had called it quits, and when Garfunkel followed suit in 1973 with Angel Clare, their solo paths were set: Simon on his somewhat unpredictable and occasionally inscrutable multi-platinum quest, Garfunkel continuing to use his striking vocal gift to interpret others' songs. They'd periodically reunite over the years for tours and recording projects, and nearly came back together during the sessions for Simon's 1983 Hearts and Bones LP, but the duo was essentially finished as creative partners.

"Partnerships ... are destined to break up, as are most business partnerships," Simon said years later. "And just after a while, everybody gradually changes, and has their own agenda of what they want to do in life, and it doesn’t coincide with the way it did in the very beginning. And so, you’re naturally inclined to go your separate ways."

The music, however, remains – and remains capable of restoring that connection, however briefly. "It's bigger than the two of us. We meet somewhere in the air through the vocal cords and we're very close. We're real brothers, somehow, in that moment," reflected Garfunkel long after the breakup. "We both respect the good, you know? In this crummy world where the mediocre is good enough, we really chase after something better."

In a 2006 interview with the Independent, Simon took stock of the legacy he carved out with his old partner: "After all these years it's still a name that fills stadiums all over the world. I wouldn't have predicted that," he said. "To my surprise, I'm proud of the impact of Simon & Garfunkel. The work is pretty good for young work. What strikes me is that it wasn't angry; there was nothing nasty about it; it was kind. It was sophomoric when it missed; it was sentimental when it missed. But when it hit, it had a purity. And when I look back I think: 'He must have been a nice guy. He must have been in love with the world.'"

Paul Simon / Simon and Garfunkel Albums Ranked

Rock Feuds: Simon vs. Garfunkel

More From Ultimate Classic Rock