The History of Pete Ham and Badfinger

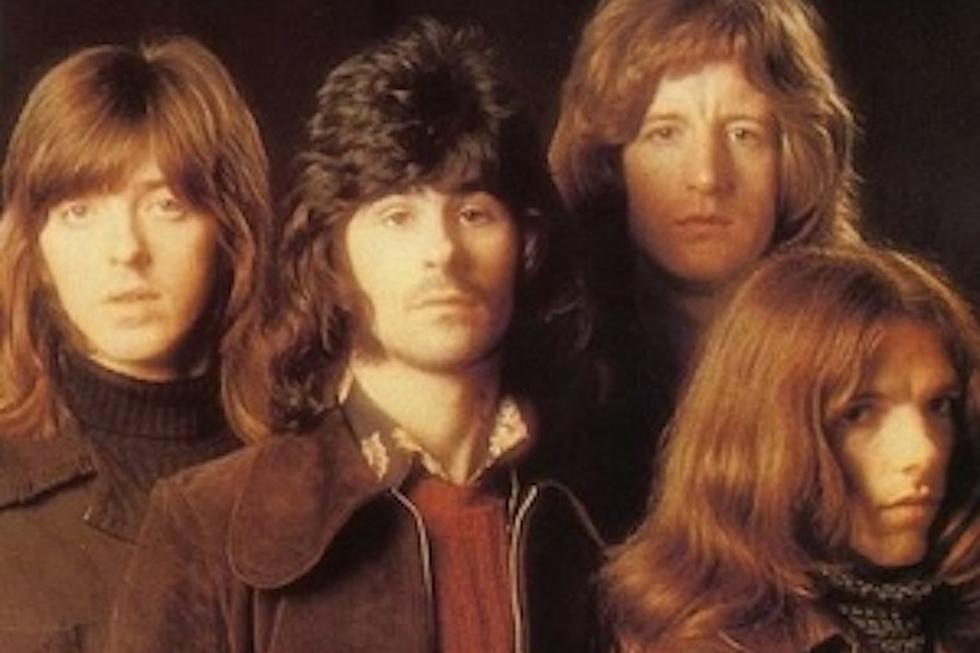

Like the Beatles, the band with which they’re inextricably linked, Badfinger included four men capable of writing and singing lead. Though they didn’t have a traditional frontman, Pete Ham has often been called the heart and soul of the group since he was the composer and voice of their biggest hits. His story is a complicated and tragic one.

Born on April 27, 1947 in Swansea, Wales, Ham was bitten by the rock 'n’ roll bug at an early age. He formed his first band, the Panthers, at age 14. By late 1966, they had changed their name to the Iveys and moved into the London house of manager Bill Collins. While playing covers throughout London, Ham honed his songwriting chops by making home demos into a Revox two-track tape recorder. Those songs, and others from throughout Ham’s life, would be released in 1997 as 7 Park Avenue (named after the address that birthed the songs), with Golders Green (the section of London where he lived) coming two years later and Keyhole Street following in 2013.

Ray Davies of the Kinks got wind of the Iveys — which then consisted of Ham, guitarist David Jenkins, bassist Ron Griffiths and drummer Mike Gibbins — and produced some demos in early 1967. Those sessions didn’t pan out as they had hoped, but a year later, the group attracted the attention of an even bigger name in England's rock elite.

Shortly after wrapping up recording with Davies, Collins ran into Beatles road manager Mal Evans, an old acquaintance, and told him about his group. By the middle of 1968, the Beatles had formed Apple Corps and were looking for acts for the company's record label. Evans played the Iveys’ demos for the Beatles, who were impressed enough to sign them.

The first single, an Evans ballad called “Maybe Tomorrow,” was released in November. Despite a soaring chorus and a lush, orchestral production by Tony Visconti, the song stalled at No. 67 in the U.S. and failed to even chart in the U.K. But it performed well in Germany, Italy and Japan, which led to Griffith’s “Dear Angie” getting a single release in only those countries. Unfortunately, the next songs the band submitted to Apple were rejected, either because the label didn’t hear a hit or Apple was having financial difficulties.

Listen to Badfinger Perform ‘Maybe Tomorrow’

Either way, help arrived in the form of Paul McCartney, who heard of their frustration. He gave them a demo of a song he had quickly written for the Peter Sellers movie The Magic Christian, and told them to copy it verbatim and they would have a hit. The gambit paid off. “Come and Get It” hit No. 4 in the U..K. and No. 7 in the U.S. The band's debut album, Magic Christian Music, combined their three tracks featured in the movie (which was produced by McCartney) and other songs they had recorded up to that point.

But two things happened before its release: Griffiths quit due to increasing conflicts between his family and the band. And, more importantly, not wanting to cause confusion with another group called the Ivy League, they changed their name to Badfinger, after a song John Lennon had written a few years earlier while playing piano when his finger was hurting. At the time, Lennon called it “Bad Finger Boogie,” but the tune became “With a Little Help From My Friends.”

Filling Griffiths' void was guitarist Joey Molland, with Evans switching to bass. In the wake of the Beatles’ breakup, Badfinger found themselves as their hand-picked successors. All four contributed to George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, and Ham and Evans sang backup on Ringo Starr’s “It Don’t Come Easy.” A year later, Evans and Molland added acoustic guitars to a few songs on Lennon’s Imagine album, and the entire group performed at Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh.

Their friendship with the Beatles would be a blessing and a curse throughout their career: It brought ears to their music, but it also drew comparisons that no band could ever live up to, even as good as Badfinger were. It didn’t help that they wrote harmony-rich songs with a heavier rock crunch that reflected the times, a sound that would later be referred to as “power pop.” But they weren’t just aping their bosses. Still, they knew they needed a self-penned hit in order to establish their identity.

Listen to Badfinger Perform ‘No Matter What’

The only single from the group's next album, No Dice, gave Badfinger what they wanted. Written by Ham, “No Matter What” matched the success of “Come and Get It,” reaching the Top 10 in both the U.S. and U.K. Produced in part by Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick, No Dice (which included several other beautiful compositions by Ham, such as “Midnight Caller” and “We’re for the Dark”) peaked at a respectable No. 28. Another tune seamlessly combined the verses from Ham’s “If It’s Love” with the chorus of Evans’ “I Can’t Live.” Their new song, “Without You,” caught the ear of Harry Nilsson, who recorded it for Nilsson Schmilsson later that year. His version spent four weeks at No. 1; in 1994, Mariah Carey took it to No. 3.

Though they had achieved their own success, a Beatle came calling again, when Harrison offered to produce the follow-up after the initial sessions in early 1971 with Emerick didn’t go well. A little more than a month into the recording, Harrison was called away to help put together the Concert for Bangladesh. In addition to having famous friends like Starr, Eric Clapton and Bob Dylan on the bill to raise money for the refugees of the war-torn and flood-ridden nation, Harrison asked Badfinger to be part of his backing band, recreating the parts they played on All Things Must Pass. Ham also performed an acoustic duet of “Here Comes the Sun” with Harrison.

After the concert, Harrison’s continuing commitments to Bangladesh meant that he couldn’t finish producing the album. So Badfinger hired Todd Rundgren, who was similarly versed in Beatlesque rock. By early October, Straight Up, was complete. Though songwriting contributions were split almost evenly among Ham, Evans and Molland, two of Ham’s songs were chosen as singles. The first, “Day After Day,” became their biggest-ever hit, reaching No. 3. The follow-up, “Baby Blue,” didn’t build upon its predecessor’s momentum, but still managed to climb to No. 14.

Normally, this would be the part of a classic rock band’s story where they’re rewarded for years of hard work with a decade’s worth of hit albums, stadium tours and millions of dollars. But Badfinger weren’t an ordinary group. The successes of 1971-72, including the Nilsson cover, would be their apex.

Listen to Badfinger Perform ‘Day After Day’

Touring had always been a problem, particularly in the U.S. They were all solid musicians and singers, but reproducing the records onstage – especially the dense, layered harmonies – was difficult. Additionally, they were sharing bills with prog and hard-rock bands. To avoid getting booed offstage, they would often have to play sets consisting largely of extended boogie jams or covers. Dave Mason’s “Feelin’ Alright” and Little Richard’s hits always worked, but at a time when originality and innovation in rock was in high demand, it reflected badly on Badfinger, who were still having difficulty shaking the "next Beatles" tag.

Around the time they started work on No Dice, they hired Stan Polley, a New York-based businessman with some experience in the music industry, to look after their money. Their agreement gave him power to negotiate all contracts, and he kept the members on salary throughout this time, paying them out of the royalties he was collecting on their behalf.

By 1972, Apple was falling apart. With Badfinger owing the label one last record, Polley looked for a new company where he could get more favorable terms for his clients. He found one in Warner Bros., which signed the group to a $3 million deal for six albums in three years. It would start as soon as their contract with Apple expired.

Back in the studio, Badfinger were once again running into problems. Sessions with Rundgren didn’t go well, and Chris Thomas was then brought in to produce. The delay, which was furthered by an issue regarding Molland’s copyrights and Gibbins' temporarily leave of the group, killed any momentum they had achieved. When the album, Ass, was eventually released in November 1973, it flopped. Molland wrote five of its 10 songs, but the only single pulled from the record was one of Ham’s two tracks, “Apple of My Eye,” which reflected his mixed emotions about leaving the company that gave them their break. The song just missed the Billboard Hot 100, and Ass stalled at No. 122.

Listen to Badfinger Perform ‘Apple of My Eye’

The band's new contract took effect while Badfinger were waiting for Ass to come out. As a result, their first LP for their new label, Badfinger, arrived in February 1974, only three months after Ass. It continued the downward commercial trend, not getting any higher than No. 161. Neither of its singles charted.

Meanwhile, Warner Bros. was beginning to wonder what Polley had done with the advances that had been placed in escrow. The band’s lack of money, coupled with sales declines, caused a great deal of tension in the studio. By late August, after the album had been completed, the situation came to a head. Ham, the only member of the group who still trusted Polley, walked away from the band and was briefly replaced by keyboardist Bob Jackson but returning a few weeks later.

Molland quit on the eve of the November 1974 release of Wish You Were Here, which gave Badfinger the best reviews they’d had in years. With Jackson again in tow, they immediately started to record a follow-up LP, but the sessions were halted in mid-December by Warner Bros., which ended its contract with the group due to Polley’s refusal to account for missing money. Wish You Were Here was immediately pulled, even though it was still climbing the charts at No. 148.

Over the next few months, Ham was driven deep into depression over his lack of money. On the night of April 23, 1975, he went out drinking with Evans, where they decided to fire Polley once and for all. Evans brought Ham home shortly after midnight when – as recounted in Dan Matovina’s excellent biography of the band, Without You: The Tragic Story of Badfinger – Ham told Evans, “Don’t worry. I know a way out.”

Ham’s girlfriend Anne, who was eight months pregnant with their child, woke up the next morning and went to the garage where Ham often wrote. She found him hanging from an overhead beam. Ham was three days away from his 28th birthday. The note he left was addressed to her and her son. It read, “Anne, I love you. Blair, I love you. I will not be allowed to love and trust everybody. This is better. P.S. Stan Polley is a soulless bastard. I will take him with me.”

Listen to Badfinger Perform ‘Just a Chance’

Badfinger broke up after Ham's death, but Molland recruited Evans for another project in 1978, which led a revival of the band’s name. They recorded two albums for Elektra: 1979's Airwaves and 1981's Say No More. Both records placed singles in the middle of Billboard’s Hot 100. But Molland and Evans then split up, launching competing versions of the group for a couple of years, with Evans bringing back Gibbins.

Though Evans was now getting royalties from “Without You,” money problems dating back to the Apple years had never been sorted out. He called Molland on Nov. 18, 1983, to see what more they could do. A long argument took place, and Evans slammed the phone down screaming, “I’ll be dead before I get the money,” according to Matovani. Later that night, Evans – who was 36 years old – hanged himself from a tree in his garden.

Molland and Gibbins continued touring throughout the ‘80s. In the early ‘90s, their Apple albums (except for Ass) were reissued on CD, which coincided with a renewed interest in power pop thanks to the popularity of alternative acts like Matthew Sweet and Teenage Fanclub. In addition to the Ham demos that were released around this time, Head First — the record Badfinger were working on when Warner Bros. shut down the sessions — and other outtake compilations arrived over the next decade. Ass was finally reissued in 2010.

Matovina’s book goes into considerable and heartbreaking detail of the many business transactions — particularly the contracts and the lawsuits — among the band, Polley, Apple and Warner Bros. over the years. Eventually, everything was sorted out between Badfinger and their two labels, with Ham’s estate receiving between $80,000 and $200,000 annually from royalties.

That total increased in 2013, when “Baby Blue” was used in the last scene of the final episode of Breaking Bad. Nearly 5,000 copies of the song were sold on iTunes immediately after the show aired, pushing the 40-year-old cut into iTunes’ Top 20. Earlier that year, on what would have been his 66th birthday, Ham was honored in Swansea with a blue plaque near the Ivey Place entrance of the train station, which isn't too far from where the Iveys used to practice.

Polley pleaded guilty in 1991 to charges of swindling $250,000 from another client in an unrelated case. He was sentenced to five years probation and ordered to return the money. He died in 2009, having paid back only a fraction of the amount.

See How Badfinger and Others Got Their Names

More From Ultimate Classic Rock