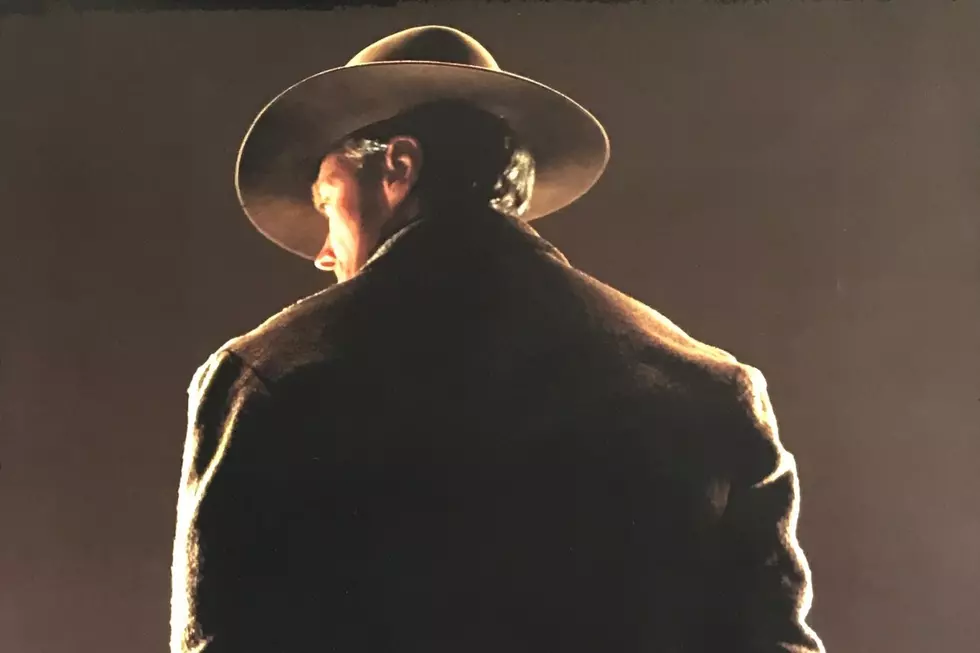

50 Years Ago: Clint Eastwood Gets Musical in ‘Paint Your Wagon’

One of the many fascinating things about Paint Your Wagon is the amount of talent that went into bringing it to the screen, particularly given how badly it bombed.

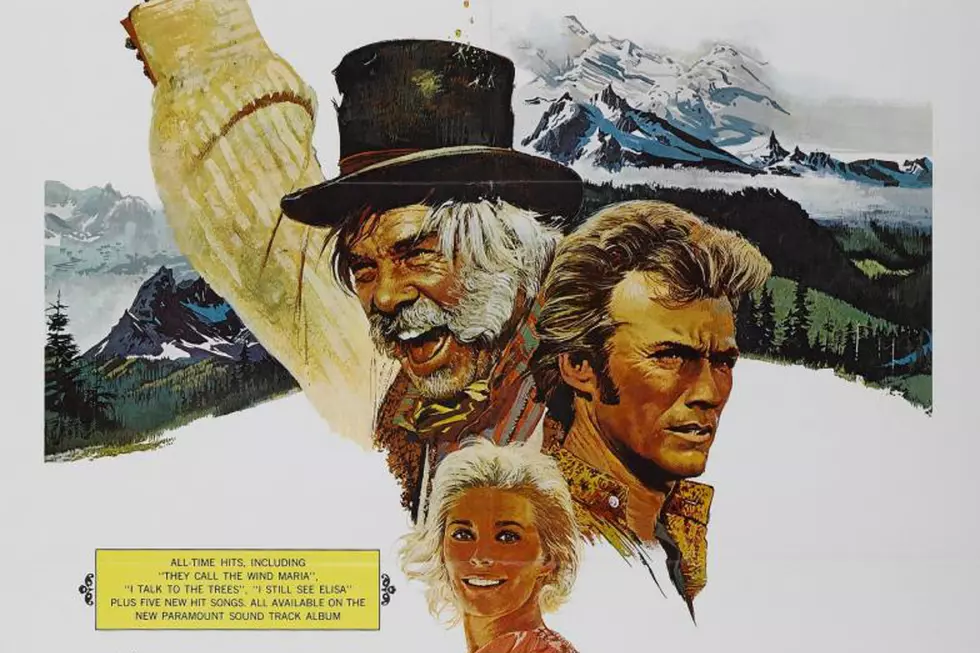

Released on Oct. 15, 1969, the movie stars Clint Eastwood, then at the beginning of his ascent to superstardom, Lee Marvin, already almost two decades into his extraordinary career, and Jean Seberg, a screen icon in both the United States and France. It was based on a successful Broadway musical by the team of Lerner and Loewe, who also penned My Fair Lady, Camelot and Brigadoon. Several additional songs for the film version were composed by four-time Oscar winner Andre Previn, a giant in his field.

The screen adaptation was written by Paddy Chayefsky, one of the greatest screenwriters of his generation, who won Academy Awards for Marty (1955), The Hospital (1971) and Network (1976). And the cinematographer was William A. Fraker who also shot, among many other things, Bullit (1968), Rosemary's Baby (1968), Heaven Can Wait (1978) and Tombstone (1993).

Despite this accumulation of luminaries, on its release Roger Ebert wrote that Paint Your Wagon, "doesn't inspire a review. It doesn't even inspire a put-down. It just lies there in my mind -- a big, heavy lump." His opinion was echoed by most reviewers, and for decades the movie has been seen by critics as a boondoggle. It was a musical western made at the precise moment musicals had passed their expiration date, it came in at twice its projected budget and ended up losing money, and it was a symbol of an out of touch Hollywood, unable to adapt to the changing culture of the late 1960s.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the graveyard of forgotten films. Paint Your Wagon has become much more popular with the passing years than critics ever seem to have suspected it would be. On Rotten Tomatoes, for example, while only 27% of the critics rank the movie as "fresh," 68% of the audience does so, and this with over 8,000 ratings.

The reason for this might be that the film combines a number of delightful elements with one rather disastrous one. The positive ingredients include the story, the slyly satirical take of masculinity and frontier life, and Marvin's performance. The downfall is that the film just never seems to work as a musical, and despite the fact that several of the songs are wonderful (several others are not) almost all of them feel shoe-horned into what might otherwise be an enjoyable comedic endeavor.

The plot opens with a grizzled old prospector in the mountains of California named Ben (Marvin) witnessing a wagon from a train of settlers crashing into a ravine. One man is killed, and his brother – who will come to be known only as "Partner" (Eastwood) – only barely survives. When Ben and the other settlers dig a grave for the fallen man, they discover gold in the dirt. Ben stakes a claim on the spot, takes Partner as his partner, and a town is born.

Soon the town, dubbed "No Name City," is booming. But these men have a serious problem: there are no women. This changes when a Mormon passes through, with two wives in tow. The men of No Name City are at first astounded by this arrangement, and then outraged; they rather forcefully suggest that the Mormon sell one of his wives. Ben, drunk as is his wont, staggers into the auction and buys Elizabeth (Seberg) for the astounding sum of $800.

This, of course, does nothing to solve No Name City's problem, so they send a mission out to hijack a stagecoach carrying French prostitutes to another boom town. The caper sends the whole town spiraling into debauchery, with more saloons and brothels popping up in rapid succession; at the same time, Ben must confront the fact that Partner and Elizabeth have fallen in love. But instead of destroying Ben and Elizabeth's relationship, this only expands it.

In a neat reversal of the Mormon's situation at the beginning of the film, Elizabeth decides that she would like to be married to both Ben and Partner, and so the three live together as man and wife and man.

In the second half of the film Ben and Partner, facing the prospect of a long cold winter without much income, devise a plan to tunnel under all the buildings in town and thereby collect the gold dust that’s falling through the floorboards when drunken miners spill it. At the same time, a party of civilized, god-fearing farmers arrives in town and begins to stir up a yearning for respectability in Elizabeth and Partner. The movie ends with Ben and Partner's tunnels collapsing, sending No Name City careening wholesale into the earth. Ben and most of the other miners, terrified by the prospect of more farmers and more civilization arriving to remake the destroyed burgh, set out for new adventures. Partner stays home to make a life with Elizabeth.

It must be said that there is a certain interest in actually hearing Marvin and Eastwood sing. The former does absolutely nothing to try to disguise the fact that his rough, croaking vocal cords were not built for the job, the latter carries his tunes in a passable, if amateur, croon. (Seberg was the only one of the three principals not to sing her own part.) But the real charm of the film lies in watching an attempt so large and goofy and quixotic that very nearly, despite itself, succeeds.

The script is both broad and sly, and is filled with memorable one-liners and gags. It's also aided immeasurably by Marvin's comedic performance. A decorated World War Two combat marine who cut his acting teeth playing psychopaths in The Big Heat (1953) and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence (1962) and then moved on to portraying legendarily tough anti-heroes in Point Blank (1967) and The Dirty Dozen (1967), Marvin here employs everything from goofy pratfalls to a cornucopia of exaggerated facial expressions to stimulate laughs, not taking a single scene off. It's a career highlight.

Marvin also does a great deal to forward the film's satire. In addition to its surprising embrace of a woman-centric polygamous relationship, Paint Your Wagon delivers a winking revision of the myth of American expansion. The foundational element of this myth, particularly as explored by Western movies, is the clash between civilization and wilderness. In Paint Your Wagon this clash is flipped wonderfully on its head. Here, American manifest destiny – the civilizing of the wilderness – is driven by nothing more noble than a lust for gold and a hatred of honest work. The only thing that the men who drive that destiny love more than whisky and cigars is women, and the only thing that truly scares them is the thought of a life without debauchery.

Though Paint Your Wagon was not an initial commercial success, its continuing place in pop-culture has given the film lasting longevity. The movie has been quoted on everything from the Academy Awards to Mystery Science Theater 3000, ensuring that it won’t soon be forgotten. Even the Simpsons made reference to the flick, in a scene in which Homer sits down to watch a bloody Western, only to be shocked by the musical numbers emanating from his screen.

'Dirty Harry' Movies Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock