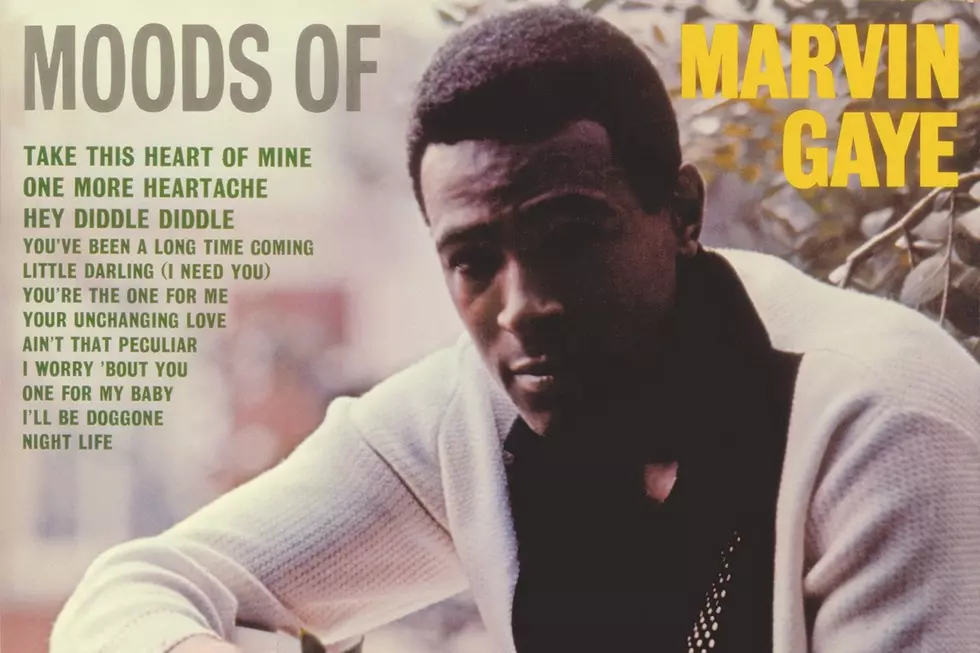

55 Years Ago: How ‘Moods of Marvin Gaye’ Changed Everything

Marvin Gaye actually revealed himself as more than the typical Motown factory drone well before 1971's What's Going On. He just hadn't quite harnessed those ambitions yet.

A desire to break the mold, to confound popular music's built-in expectations, eventually led Gaye to frank musical discussions about war, the environment and social justice. When Moods of Marvin Gaye arrived on May 23, 1966, however, he was still engaged in the dead-end pursuit of becoming a celebrated interpreter of the Great American Songbook.

In some ways, it made sense. He certainly had the style and grace, and success with sophisticated covers of ageless favorites popularized by the likes of Frank Sinatra, Billie Holiday and Nat "King" Cole would have placed him well outside any R&B convention.

"Marvin could sing anything," Moods of Marvin Gaye coproducer Smokey Robinson told Rolling Stone in 2010, "from gospel to gutbucket blues to jazz to pop."

The problem is he wanted to, but audiences weren't all that interested. Neither, of course, were Gaye's label bosses. So, he followed up 1965's A Tribute to the Great Nat "King" Cole with Moods of Marvin Gaye, an album that split the difference. He sang songs by Robinson and Stevie Wonder, while also covering Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer.

It quickly became brutally obvious which ones the buying public preferred. Gaye had no problems with the old chestnut "One for My Baby (And One More for the Road)" and even more deftly handled Willie Nelson's twilight classic "Night Life." But only the R&B stuff hit, as Robinson's "Ain't That Peculiar" and "I'll Be Doggone" became Gaye's first million sellers.

Listen to Marvin Gaye's 'Ain't That Peculiar'

For Robinson, that felt almost preordained. Seems he always had Gaye in mind for "Ain't That Peculiar": "We were on tour, and [Miracles bandmate Marv Tarplin] came to me because he had that guitar riff, which I thought was awesome," Robinson later remembered. "And we wrote the song right there. It was specifically for him."

The single became the first of four Top 20 R&B-themed smashes to emerge from Moods of Marvin Gaye. Robinson, who also cowrote "One More Heartache" (No. 4) and "Take This Heart of Mine" (No. 16) for the LP, already recognized something deeper moving beneath the surface with Gaye.

"I spent a lot of time waiting for Marvin," Robinson told Rolling Stone. "See, Marvin was basically late coming to the studio all the time. But I never minded, because I knew that whenever Marvin did get there, he was going to sing my song in a way that I had never imagined it. He would 'Marvinize' my songs, and I loved it."

Unfortunately, "One for My Baby" was just as quickly forgotten – and things were even rougher out on the road. Gaye had begun to focus more on supper clubs rather than typical concert venues geared to youth. He wore a tuxedo, in the sartorial manner of mid-century crooners, further separating himself from his soul-singing roots.

Frankie Gaye's memoir Marvin Gaye, My Brother set the scene for a contemporary appearance at Bimbo's 365 Club in San Francisco, as Marvin "strolled out looking so suave in a top hat and tails, of all things, acting like Romeo but coming across as the Dapper Dans in '30s movie musicals."

That engagement presaged what Gaye must have imagined would become a signature moment during his extended stand that August at the Copacabana. Located adjacent to Central Park in New York City, the posh venue welcomed Gaye's surprising penchant for cabaret material, but the Motown stuff was more likely to be met with curious stares.

A determined Gaye told Billboard in 1966 that he still felt "very strongly about R&B," but "I'd like to become known as a more versatile singer." The headline, however, summed up his musical conundrum: "Gaye, Popping With Pop, Keeps Eye on 'First Love.'"

Listen to Marvin Gaye's 'I'll Be Doggone'

In truth, his career direction was already obvious: Moods of Marvin Gaye, like 1965's How Sweet It Is to Be Loved by You, became a Top 10 R&B hit album while songbook-focused projects including 1964's Hello Broadway failed to chart anywhere. Motown recorded Gaye's 1966 dates in New York City with an eye toward releasing a live album but ended up shelving the project indefinitely.

Clearly stung, Gaye would record a few other non-R&B tracks but never returned to the Copacabana. Instead, he retreated deeper into the studio, focusing on duets with Tammi Terrell in the run up to an initial creative breakthrough with 1968's heartbroken and mysterious "I Heard It Through the Grapevine."

"I'm not especially an entertainer," Gaye later admitted to The Washington Post. "I'm an artist and an entertainer, but the two are completely different. With one I'm extremely happy and joyful and at peace, and with the other I'm frankly out of my element. Although I do it okay, I do it nicely and everything, it's not where I get my biggest kick."

This is where his true legacy would soon be forged. Gaye wasn't going to shake off Motown's shackles by looking backward to some of the country's most treasured standards, no matter how tastefully done. (And no matter how undeniably great he looked in a tuxedo.) Marvin Gaye would have to dig deeper, to get more real.

Just as crucially, however, he'd achieve freedom only through fame. A platform of success was needed in order to launch one of the most remarkable transformations in all of music. Gaye needed to become undeniable. In many ways, that started with Moods of Marvin Gaye – just not in the time or manner he once hoped it would. Patience finally paid off with What's Going On.

"Marvin was much more than just a great singer. He was a great record maker, a gifted songwriter, a deep thinker — a real artist in the true sense," Robinson told Rolling Stone. "Marvin was always worth the wait."

Top 25 Soul Albums of the '70s

More From Ultimate Classic Rock