How Depeche Mode Finally Broke Through With ‘Violator’

The months leading up to Depeche Mode's seventh album were marked by a growing interest from outside the core goth audience that had been loyal to the English synth-pop band since a string of mid-'80s albums landed on college-radio playlists.

The Music for the Masses tour in 1988 culminated in a sold-out show at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, Calif., and the release of the "Personal Jesus" single in August 1989 gave the group its first Top 40 showing in the U.S. since "People Are People" reached No. 13 in 1984.

So, when Violator arrived on March 19, 1990, it seemed like a watershed moment for the band, separating past niche achievements from new ambitions to take its music to bigger and grander places. Not that any of this was out of the blue. It all had been leading there: The two previous albums -- 1986's Black Celebration and 1987's Music for the Masses -- primed fans for this leap forward.

But the leap and its aftershocks were bigger than anyone had anticipated.

Watch Depeche Mode's 'Personal Jesus' Video

The 101 concert album culled from the historic Rose Bowl show wasn't even a half-year old when "Personal Jesus" started to make its way to radio. The song was one of the first recorded with co-producer Flood for the new album and marked a pivotal change in Depeche Mode's sound.

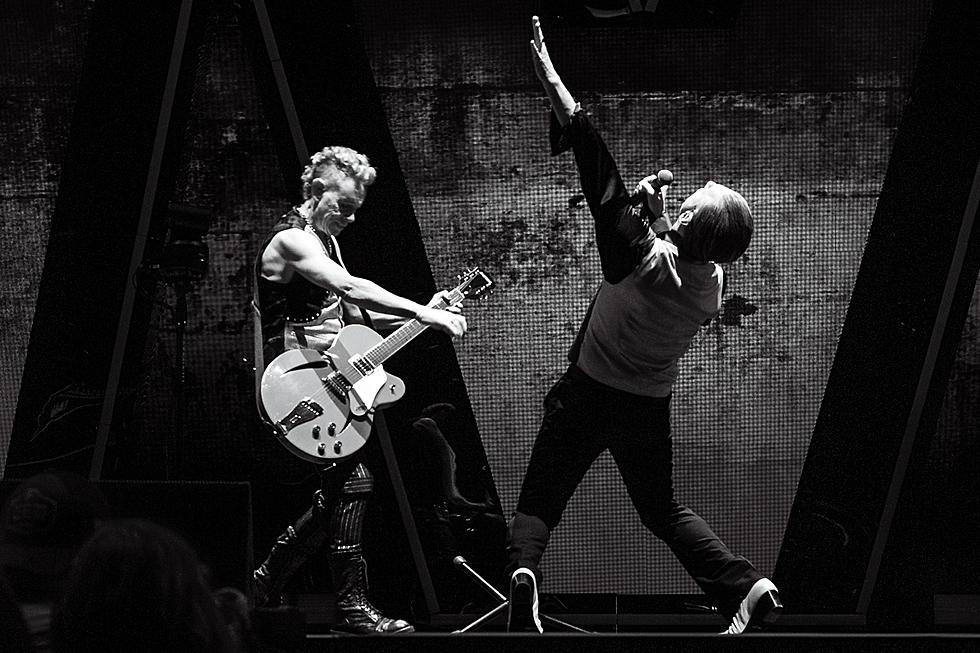

While there were a few previous tracks in their synth-heavy catalog that employed guitar, "Personal Jesus" was the first to push the instrument all the way up front. Inspired by blues music and Elvis Presley, the song pretty much qualifies as the first true rock 'n' roll number of the band's career.

And in a way it's also their first original song influenced by America, after testing the territory on 1987's "Behind the Wheel" single, which included the U.S.-road-trip-map "Route 66" as a B-side.

That distinction helped set Violator's tone from the start.

Watch Depeche Mode's 'Enjoy the Silence' Video

The opening "World in My Eyes" pulsates in a familiar way, at least at first, but it's not long before a deeper, richer listen emerges. Like the eight proceeding songs, it was written by Martin Gore, who presented mostly unfinished demos to his bandmates - a change from his usual approach that involved the group working with nearly complete songs in the studio.

Producer Flood encouraged this new method, which Depeche Mode - Gore, singer Dave Gahan and synth players Alan Wilder and Andy Fletcher - carried over into sessions that lasted eight months and included recording in Milan, London, New York and Gjerlev, Denmark. The result is a more bare, and at times almost ambient, work that distinguishes itself from its predecessors.

A darker and more brooding sense of modern rock instilled itself in the songs, a carryover from the previous two albums, but the synth-pop that dominated their earlier work, including that fluke No. 13 showing of "People Are People" in 1984, was replaced by less-springy sounds. The title of Violator was meant as a joke, an attempt to come up with a heavy-metal-sounding title. In some ways, the album isn't too far removed from that genre in both its tone and doom-y outlook.

Watch Depeche Mode's 'Policy of Truth' Video

From "World in My Eyes" to the album-closing "Clean," a five-and-a-half-minute aural feast directly inspired by Pink Floyd's 1971 experimental prog masterpiece Meddle, Violator today sounds like a band rewriting its history in 47 dark, sexy and tension-filled minutes. The singles "Personal Jesus," "Enjoy the Silence" and "Policy of Truth" all reached the Top 40, with "Silence" making it to a career-high No. 8.

With Violator, Depeche Mode became serious artists. They also became chart-topping music stars. Fittingly, the album that grabbed inspiration from various corners of America gave the band its first Top 10 LP in the States. Even though it stalled at No. 7 - the follow-up record, 1993's Songs of Faith and Devotion, was Depeche Mode's first and only No. 1 - Violator remains their best-selling album.

More significantly it altered their perspective and fans' perception of them. While the synth-pop label continued to follow the band long after guitars, live drums and deeper, darker music became fixtures in its sound, the group became a dominant force in modern-rock radio. They effortlessly transformed into arena headliners across the globe. And they graduated to rock-star status, which was accompanied by new hazards (Gahan, who became addicted to cocaine and heroin, nearly died after overdosing in 1996).

Violator arrived not long before Nirvana spun the industry in a different direction. Today, the entire album sounds like a prophetic introduction to the new decade: dark, edgy and full of anxiety. No surprise artists are still finding relevance in it decades later.

Ranking Every Depeche Mode Album

More From Ultimate Classic Rock