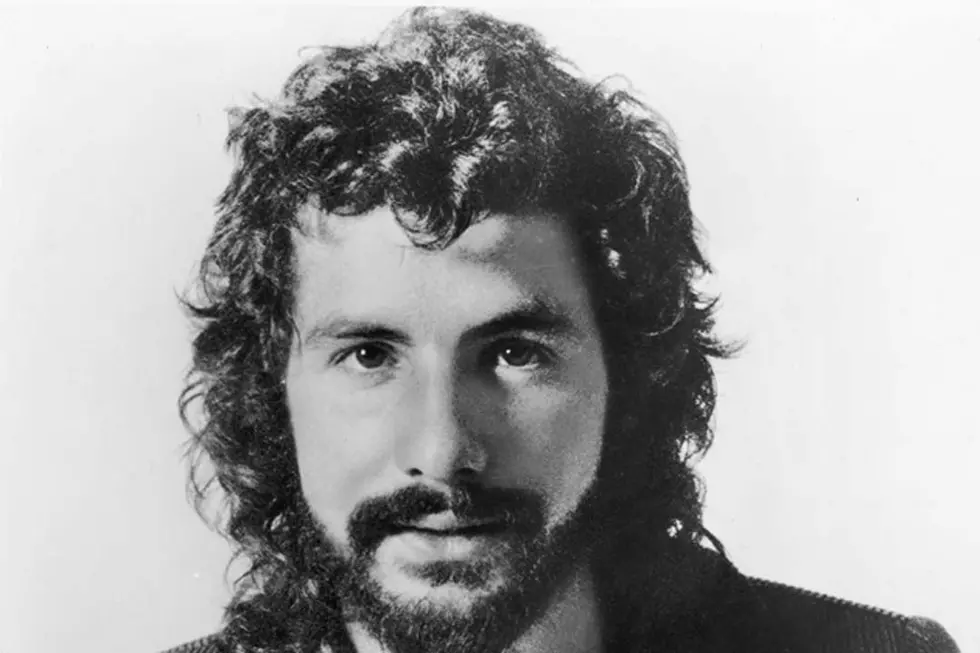

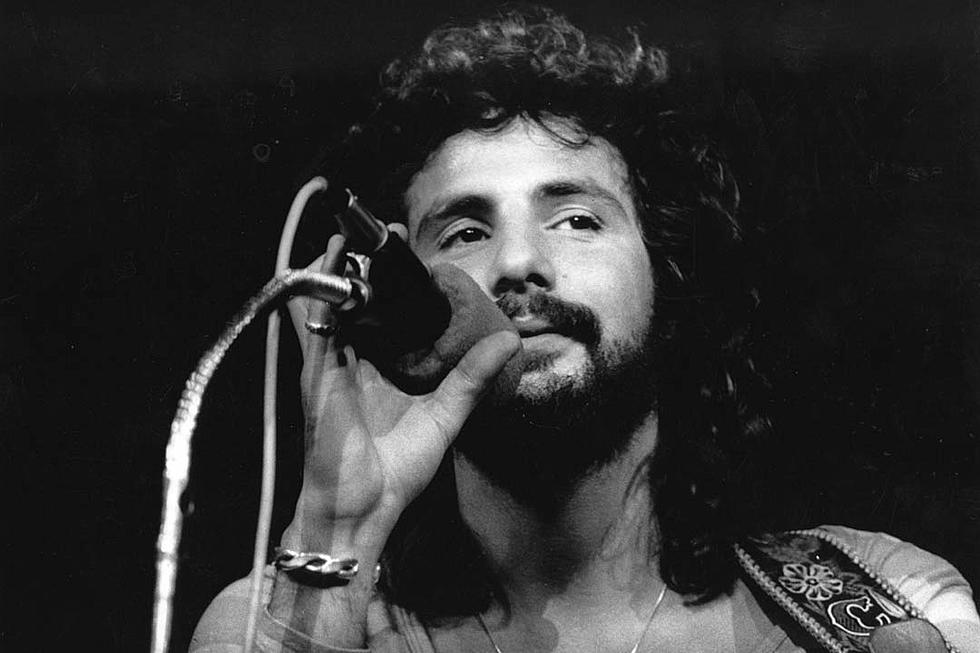

50 Years Ago: Cat Stevens Delivers His Masterpiece, ‘Tea for the Tillerman’

Cat Stevens had already released one album in 1970, Mona Bone Jakon back in April, when Tea for the Tillerman arrived on Nov. 23, 1970. And almost immediately, things changed for the 22-year-old London singer-songwriter born Steven Demetre Georgiou. And then they just didn't stop.

Stevens had been kicking around the British folk scene for quite some time, penning songs for other people and just trying to make a living when he started recording his fourth album in London during the summer of 1970. Nobody, not even Stevens, had any reason to believe that Tea for the Tillerman would sell any better than his other LPs. (Mona Bone Jakon peaked at No. 164.)

But none of his other albums contained songs as uniformly great as those found on Tea for the Tillerman, a career milestone and the album that finally helped break Stevens worldwide.

It all started with "Wild World," his first Top 40 single (which stopped just shy of the Top 10 at No. 11), and ended a little more than a year later, when the cult movie Harold and Maude used Stevens' songs (including a handful from Tea for the Tillerman) on its soundtrack. And it was all setup for his biggest success in 1972 with "Morning Has Broken" (which hit No. 6) and the album Catch Bull at Four (which hit No. 1, his only LP to do so).

But Tea for the Tillerman is the album that made Stevens a star, the one that introduced his voice (soft, quivering, delicate and raspy at points) and songwriting (sharp, moving, eminently hummable) to a larger audience.

Prior to Tillerman, he was best known as the guy who wrote "The First Cut Is the Deepest," which R&B singer P.P. Arnold had a hit with; afterward, he became one of the most representative voices, faces and personalities of the '70s' folk movement.

Listen to Cat Stevens' 'Wild World'

From the opening "Where Do the Children Play?" (an ecologically minded survey of the era's deadliest threats) and "Hard Headed Woman" to "Wild World" and "Father and Son" (one of the most moving songs ever written about the divide between parents and children), the album is a soft-rock landmark -- made primarily on acoustic instruments, including congas, double bass and violin -- that's as timeless as it is a part of its generation.

After the album's success, Stevens pretty much followed its template for most of the '70s, until his career dried up at the end of the decade. The majestic arrangements, the driving force behind many of Tea for the Tillerman's songs, almost sound neutered in later recordings. But here they shake things up, giving lift to everything around them. Stevens relied on them later; on Tillerman, they were just another piece of the creative process that helped define the album and, in turn, helped define the artist.

The Top 100 Rock Albums of the ‘70s

More From Ultimate Classic Rock