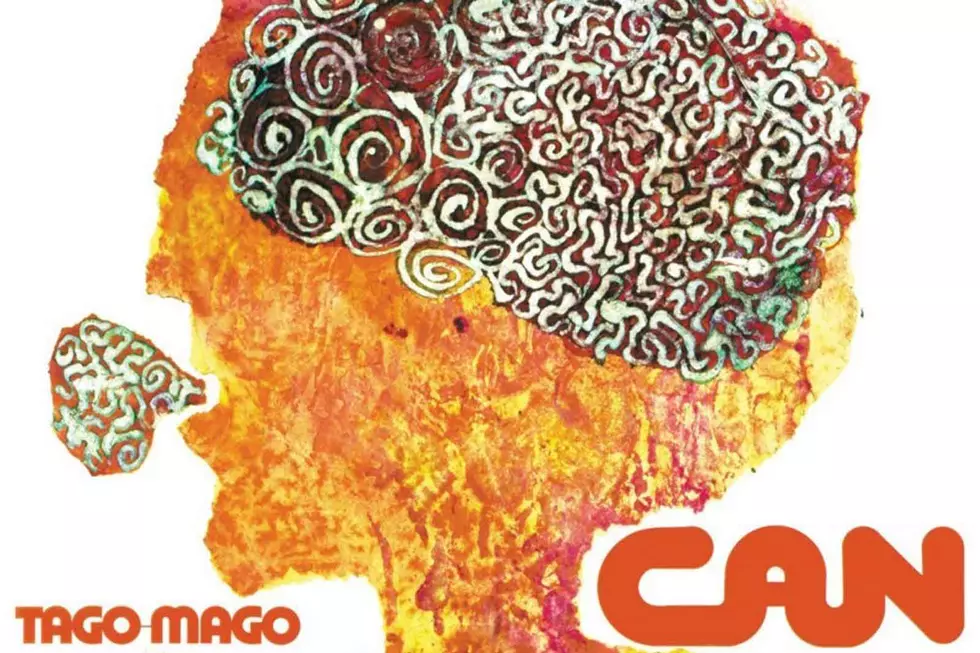

50 Years Ago: Can Push the Limits of Rock Music on ‘Tago Mago’

In August 1971, when Can released their second album, Tago Mago, there wasn't a whole lot that sounded like it. A half-century later, there's still not much in the music landscape like that record.

The German krautrock band's first album, 1969's Monster Movie, included many of the same elements featured on the follow-up: dashes of experimental music and psychedelia, along with an epic, side-long song with an unconventionally spelled title. But between those two records the quintet got a new singer.

And while Monster Movie's vocalist, Malcolm Mooney, a Black American, helped launch Can – he gave the group its name and was pivotal in shaping its sound – the addition of the Japanese-born Damo Suzuki on Tago Mago proved to be a significant moment in their career and in the many genres they would transverse.

Mooney returned to the U.S. in early 1970 after suffering a mental breakdown. He helped establish the band's mix of avant-garde experimentalism and garage-rock psychedelia; he was the catalyst behind the debut's 20-minute "Yoo Doo Right," which was edited from a six-hour improvisational piece.

Listen to Can's 'Halleluhwah'

But Can's out-of-control and unstructured music was all too reflective of personal problems. In mid-1970, bassist Holger Czukay and drummer Jaki Liebezeit saw Suzuki busking in Munich and invited him to perform with them that night, even though he knew only a few guitar chords and improvised all of his lyrics.

By May, he was part of the band and assisting in the recording of Soundtracks, a compilation of film music Can started with Mooney. In November, they began recording Tago Mago in a West German mansion.

For the next few months, the band holed up for sometimes more than 15 hours a day working on new music. In addition to the long jams they would run through – which Czukay then edited into more acceptable song lengths – outside sources and found sounds, like barking dogs and screaming kids, would be incorporated into the finished tracks. It was all shaping up to be a more ambitious and even more unstructured album than Can's debut.

From the opening "Paperhouse" to the LP-ending "Bring Me Coffee or Tea," Tago Mago – a double-record, seven-song set that runs more than 73 minutes – places its most astonishing pieces up front. Rhythms slowly percolate into something more delirious, Suzuki builds his voice from low rumbles to shrieking howls within the course of the songs and entire tracks unfold at a pace that can take anywhere from four ("Mushroom") to 18 ("Halleluhwah") minutes.

Listen to Can's 'Oh Yeah'

The result is an album that pushed the limits of rock music at a time when boundaries were being smashed every few months. But no other record released in 1971 sounds as outre or as forward-thinking as Tago Mago (whose title refers to an island near Ibiza called Illa de Tagomago). In so many ways, despite its influence on other artists over the decades, it's still ahead of its time.

The flow is deliberate: "Paperhouse," "Mushroom," "Oh Yeah" and "Halleluhwah," the entirety of the first two sides, drift into the occasional spaces left vacant by the propulsive rhythms with an ease that's both confident and discomforting. Suzuki was never better than he is here, riding atop the mix, and occasionally sinking below the surface, as the one dynamic rising above the hypnotic grooves.

Tago Mago became Can's definitive album and the pinnacle of the Suzuki era, which lasted for just two more records, 1972's Ege Bamyasi and 1973's Future Days. It hasn't aged much, if at all, in the years since its release. Contemporaries like Marc Bolan to post-punks including John Lydon (who based Public Image Ltd.'s sound and style on the record) to Radiohead have all cited it as direct inspiration on their work.

While many bands were hammering same-sounding, chest-rattling blues-rock into the skulls of music fans in the early '70s, Can drew influence from outside places like jazz – the improvisational playing and percussive swing are deeply rooted there – and performance art, as well as from areas nobody else was really thinking about at the time, such as cutting and pasting tape edits as a form of creative expression. Tago Wago is just as eye-opening today as it was then.

Top 25 Psychedelic Rock Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock