How George Harrison’s Weird ‘Electronic Sound’ Pointed to Bigger Things

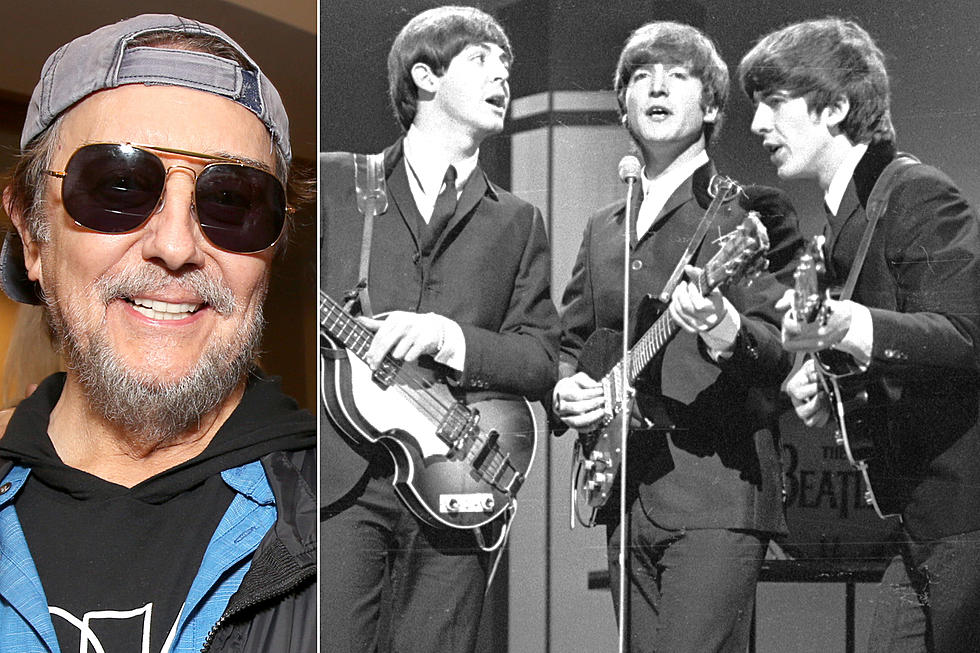

Electronic Sound stands as George Harrison's most experimental project, his worst-selling solo album and one of his more controversial ones. Released on May 9, 1969, as the second and last project on the Beatles' avant-garde imprint Zapple Records, it also opened the door for something important.

Featuring but two lengthy experiments on the then-new Moog synthesizer, one for each side, the aptly named Electronic Sound isn't so much music as it is a swirling journey through imagination and discovery – one that took Harrison as far as he'd ever venture outside of his pop-song comfort zone.

Unfortunately, it arrived just as the Beatles' money-hemorrhaging business venture Apple was restructured under new manager Allen Klein, and he promptly shut down the Zapple boutique imprint. Couple that with tepid sales – Electronic Sound peaked at No. 191 in the U.S., and failed to chart at all in the U.K. – and it's perhaps easy to see the album as a best-avoided musical blind alley.

Careful listeners, however, will note that this growing interest at the Moog directly impacted Harrison's next two projects, both of which stand at the pinnacle of his output. Harrison would contribute memorable synthesizer parts to both "Because" and "Here Comes the Sun" for the Beatles' Abbey Road, while white-noise experiments – first featured on the 25-minute side-two track "No Time or Space" from Electronic Sound – had a huge impact on John Lennon's "I Want You (She's So Heavy)," also from Abbey Road, and on "I Remember Jeep" from Harrison's titanic triple-album solo debut, All Things Must Pass, in 1970.

Barry Miles – a friend of Paul McCartney's who later wrote the authorized Many Years From Now biography – oversaw the Zapple subsidiary, had been founded back in October 1968. Its only other official release was Unfinished Music No. 2: Life With the Lions, a soundscape recording from Lennon and Yoko Ono.

Listen to 'No Time or Space' From 'Electric Sound'

Acetate copies of a third Zapple project, a spoken-word album by writer Richard Brautigan, were pressed – and there were plans for similar releases by Lenny Bruce, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Michael McClure – but Klein's intervention brought all of that to a screeching halt. "The Zapple label was folded by Klein before the record could be released," Miles later said. "The first two Zapple records did come out. We just didn’t have [Brautigan's record] ready in time before Klein closed it down. None of the Beatles ever heard it."

Life With the Lions actually charted higher, going to No. 174 in the U.S. But Electronic Sound, which began with a double-Moog essay called "Under the Mersey Wall," remains the more listenable album – if only by degree.

Reaction to Harrison's free-form release ultimately would track somewhere between confusion and outrage: "Electronic Sound," Ian Inglis wrote in the book The Words and Music of George Harrison, "is nothing more than a random, unmanipulated collection of noises and effects created on his newly acquired Moog synthesizer. To attempt to explain the 19-minute 'Under the Mersey Wall' and the 25-minute 'No Time or Space' as evidence of artistic exploration, or to describe them as avant-garde or as examples of contemporary musical solidarity, as some critics have suggested is to give the tracks a status they do not deserve. There is no evidence of structure or balance, no statement of direction or intent, no sense of texture or depth to the sounds."

But searing reviews were the least of Harrison's worries.

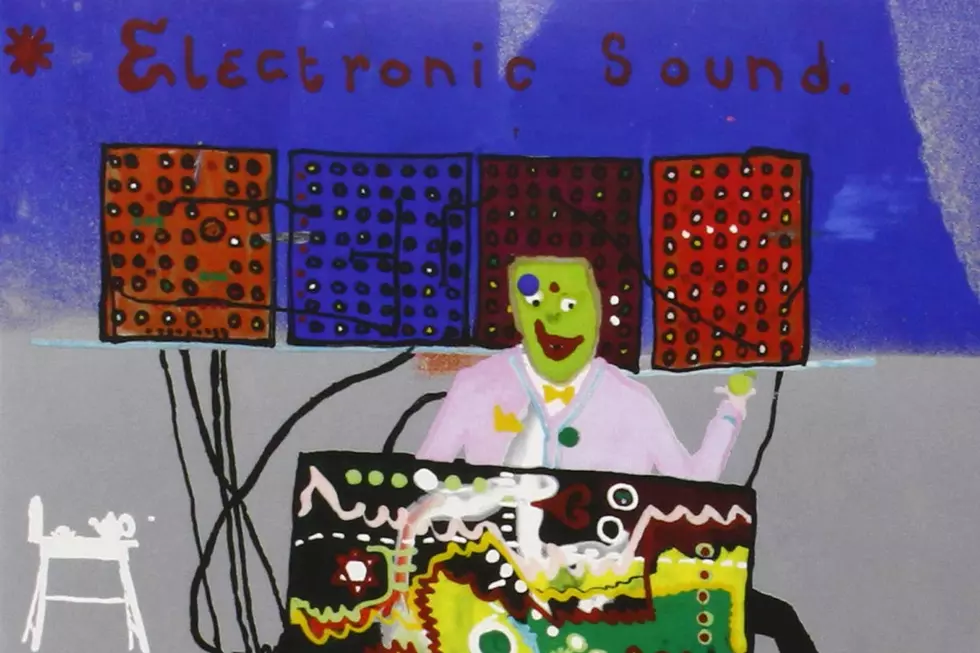

Electronic Sound featured a whimsical self-portrait as its cover – and not much else, beyond a timely quote attributed to Arthur Wax: "There are a lot of people around, making a lot of noise; here's some more." For Bernie Krause, that felt like a ripoff. He was expecting to see his name, since he'd played such a key role in the conception of the project. This dispute presaged Harrison's subsequent copyright-infringement issue with "My Sweet Lord" from All Things Must Pass.

The roots of Electronic Sound initially grew out of a sessions for Jackie Lomax, for whom Harrison was producing a debut recording for Apple. There, Harrison was introduced to Krause, a former member of the Weavers who'd become deeply involved with the emerging analog synthesizer technology. Krause, in fact, had contributed Moog to the Monkees' version of "Star Collector" back in 1967.

Listen to George Harrison's 'Under the Mersey Wall'

Krause ultimately added Moog parts to five Lomax songs, recorded at Sound Records Studio in Los Angeles in November 1968. Intrigued, Harrison asked him to further explore the instrument after the Lomax sessions concluded. Krause later contended that this demonstration, recorded in the early hours of Nov. 12, was subsequently edited down to become "No Time or Space" on Electronic Sound.

"As I showed him the settings and gave some performance examples, Harrison seemed impressed with the possibilities. I had no idea at the time exactly how impressed he was," Krause wrote in his book Into a Wild Sanctuary: A Life in Music and Natural Sound. "Had I been aware that he was recording my demonstration, I would have never shown examples of what [I was] considering for [my] next album."

Krause didn't have the funds to take on the Beatles. "Although I did get credit on the inside jacket, along with his cats, I never did receive a single quid," Krause wrote. "His refusal to acknowledge the source where he acquired the expropriated material left me frustrated and angry, but also with a feeling of powerlessness."

Into the '70s, Harrison's interest in keyboards faded. Other than some additional synthesizer work on his lightly regarded 1982 solo release Gone Troppo, the late Harrison principally stuck with guitars for his subsequent work.

"All I did," he is quoted as saying by Marc Shapiro in Behind Sad Eyes: The Life of George Harrison, "was get that very first Moog synthesizer, with the big patch unit and the keyboards that you could never tune, and I put a microphone into a tape machine. I recorded whatever came out." Chris Ingham, in the The Rough Guide to the Beatles, has Harrison simply calling the album "a load of rubbish."

Eventually, Electronic Sound faded into obscurity as an of-its-time curio, and went out of print. Whatever impact it had on Harrison's career in general, and Abbey Road in particular, was similarly forgotten. "At best," Inglis concluded, "Harrison can be accused of inexperience; at worst, of pretentiousness. Either way, Electronic Sound is a pointless and rather embarrassing blot on his musical career."

Beatles Solo Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock