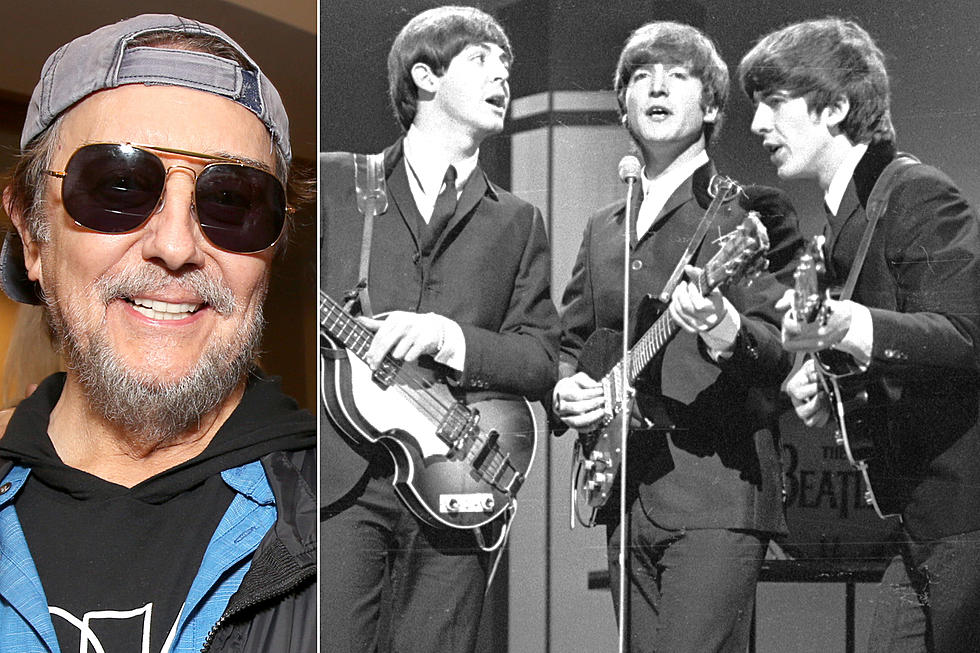

Revisiting John Lennon’s Comeback Album ‘Double Fantasy’

It's been easy, over the decades, to mythologize John Lennon's Double Fantasy. After all, we now know that when this project arrived on Nov. 17, 1980, the former Beatles star had just weeks to live. His awful murder at the hands of a delusional fan on Dec. 8 changed everything about the way the album is received.

In that brief moment before fate intervened, there were those who saw Double Fantasy for what it was: a potentially exciting, yet still determinedly tentative, step back toward music by an artist who retired a half-decade earlier.

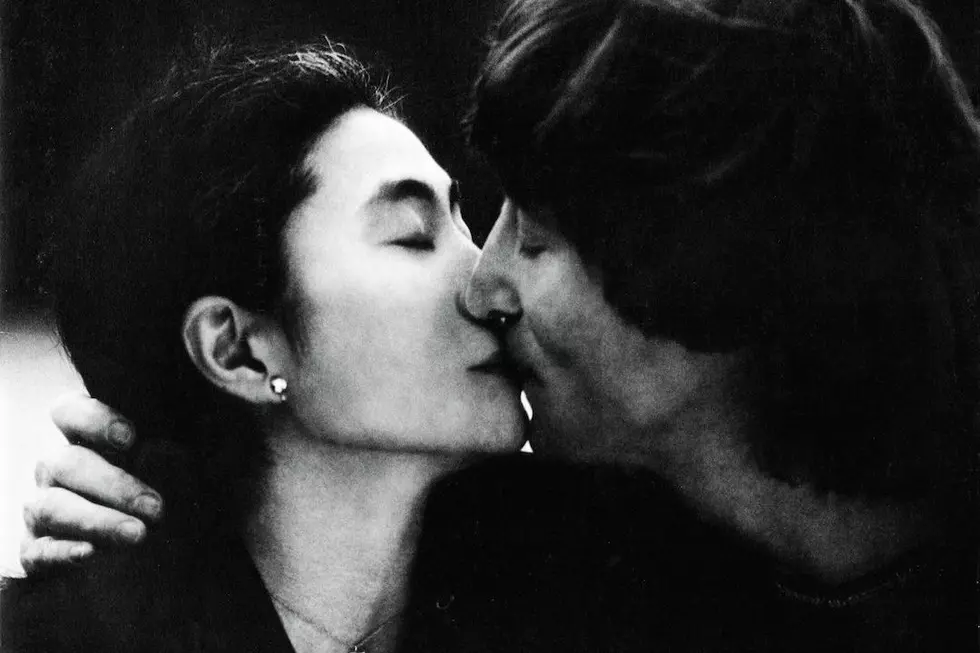

Charles Shaar, writing for NME, memorably said Double Fantasy "sounds like a great life, but it makes for a lousy record. ... I wish Lennon had kept his big happy trap shut until he had something to say that was even vaguely relevant to those of us not married to Yoko." Rolling Stone and the Village Voice, at least at first, weren't much kinder – and the record-buying public greeted the project with notable diffidence.

Double Fantasy, with its comfy domesticity and too-slick, of-its-moment production, never felt dangerous enough to be a top-tier John Lennon record. Well, at least half of the time. Yoko Ono, who was co-featured in an every-other-song format, took far more chances than he did.

It seemed, as much as anything else, like a record lost in time. Even the best of Lennon’s solo material after 1970’s Plastic Ono Band suffered from similarly dated, shag-carpet production. He loved a big sound, when sometimes a smaller one would have been more effective. Earlier in Lennon’s final decade, that meant pasting on herds of fiddles, a thudding drum clomp, gaggles of girl singers and bawdy, burlesque saxophones – something that must have brought him back to the '50s pop radio of his youth.

When Lennon returned to music after a five-year hiatus, he was still steadfastly double-tracking his vocals too. It afforded him a deeper, multi-layered sound but also needlessly softened the edges on one of rock music’s best sneers. Couple that with the compression typically employed back then, and Double Fantasy — considered apart from his death — often ended up more gossamer than necessarily great.

No matter. After Dec. 8, 1980, those earlier negative notices were forgotten as a funereal fervor pushed Double Fantasy to multi-platinum sales and a Grammy award for Album of the Year.

Seemingly forgotten was that Lennon, at his zenith, had been a scratched-and-dented treasure, laconic and all edge. Here, he seemed to have settled into a middle-aged tameness — both figuratively and, by employing the prevailing pop veneer, literally. That ultimately gave surprising gravitas to 1983’s Milk and Honey and 1986’s Menlove Ave., a pair of loose, unfinished posthumous follow-ups. (Yoko Ono added another edition to that collection when a stripped-down version of Double Fantasy was released in 2010.)

Listen to John Lennon's 'I'm Losing You'

Only on the muscular “I’m Losing You” do you get the sense of Lennon's old sinewy grit. It's the most kinetic moment on Double Fantasy, and it points to the long-hoped-for return of Lennon’s muse — the vibrant, angry yang to the bread-making househusband yin of recent years. Unfortunately, little else rises so completely out of the project's cozy, contemplative vibe.

Of course, "Starting Over" and "Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy)" resonate in entirely new ways now. There's no getting away from the awful headlines that followed – no separating this album, even decades later, from Lennon’s fate. He’ll always be 40. So, when he whispers “Good night, Sean, see you in the morning” on the latter, it’s like a cold hand closing around any fan's heart.

Meanwhile, interspersing moments like "Woman," the record's most obviously Beatlesque ballad, with a series of nervy, New Wave-influenced Ono cuts certainly helps Double Fantasy live up to its subtitle: "A Heart Play." But it also underscores something about Lennon that his devastated followers weren't willing, or maybe even able, to admit.

While Lennon was making his way back into the business, Ono was far more in sync with the prevailing post-punk zeitgeist. Lennon was only just beginning to come to terms with things as they were — with middle age, with a settled life, with love and work and parenthood. How long could it have been before he was ready to push back, and hard? Unfortunately, we never got to hear his next great rock record.

Listen to John Lennon's 'Woman'

John Lennon Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock