How John Lennon Broke With His Past on the Harrowing ‘Plastic Ono Band’

Plastic Ono Band was more than John Lennon's kiss-off to the Beatles. It was his demolition of everything the previous decade stood for, a hard-eyed confrontation with the demons that hounded him and a piercing cry for whatever love remained.

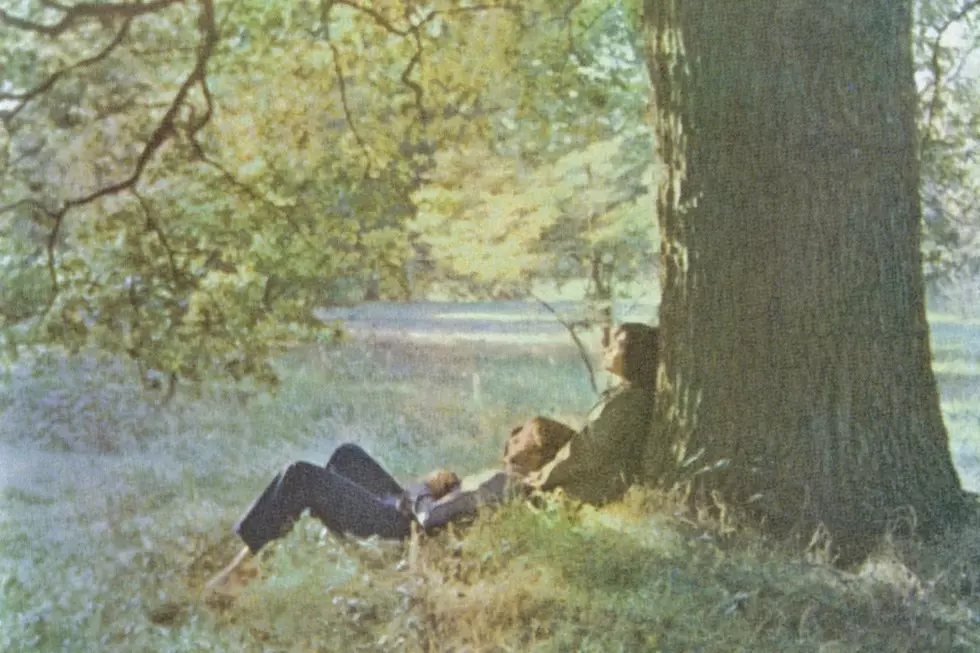

The album, released on Dec. 11, 1970, was shaped in no small way by Lennon and wife Yoko Ono's therapy experiences with Dr. Arthur Janov, an American psychotherapist who taught that repressed pain from childhood experiences could be released through primal screams. Ultimately, the duo would only last roughly four months with Janov, but the emotional dam breaking led to one of rock's most confrontational, brutally honest and harrowingly personal albums.

Though George Harrison is commonly understood to have only come into his own once he left the long shadow of Lennon's partnership with Paul McCartney, John shared a sense of rebirth in the wake of the Beatles' demise. "This time it was my album," Lennon once told Jann Wenner in one of their rangy interviews. "It used to get a bit embarrassing in front of George and Paul, 'cause we know each other so well: 'Oh, he's trying to be Elvis [Presley]; oh, he's doing this now,' you know. We're a bit supercritical of each other. So, we inhibited each other a lot."

There would be no such inhibitions here. Lennon added anguished cries for his late mom on the album-opening "Mother," then shredding his vocal chords in defiance of end-of-the-'60s ennui on "Well Well Well." He made clear his billowing disillusion on "I Found Out," framed his struggle to find something real to hang on to in "Working Class Hero," got lost for a moment in the comforts of a relationship in "Love." Then, in the album's most important statement, he blithely pushed aside fallen idols – from Bob Dylan to religion to, yes, his old band – on "God," declaring flatly that "the dream is over."

Plastic Ono Band was recorded – along with a tandem solo album by Ono – in a manner very much in keeping with the Beatles' troubled Get Back project, over the course of roughly a month beginning in September 1970 at Abbey Road and Ascot Sound Studios. The lean core group of Lennon, bassist Klaus Voormann and drummer Ringo Starr was augmented only by nominal producer Phil Spector on piano for "Love" and Billy Preston on piano for "God."

Listen to John Lennon Perform 'Mother'

"The simplicity of what Klaus and I played with him gave him a great opportunity to actually, for the first time, really use his voice and emotion how he could. There was no battle going on," Starr said in the Classic Albums: John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band documentary. "He would just sit there and sing them, and we would just sort of jam, and then we'd find out how they would sort of go and we did them. It was very loose actually, and being a trio also was a lot of fun."

Lennon would sing live with each run-through. Rare were the moments like "Working Class Hero," where he stitched together parts of two separate vocal takes. The tormented wails that conclude "Mother" were also added during a late-night session so there'd be time to rest before another round of sessions the next morning. Tracks like "I Found Out" and "Isolation" arrived with such visceral power that they distorted on the tapes.

"All these songs just came out of me," Lennon said in Wenner's Lennon Remembers. "I didn't sit down to think, 'I'm going to write about my mother' or I didn't sit down to think, 'I'm going to write about this, that or the other.' They all came out, like all the best work of anybody's ever does."

The results put a period on everything that came before, even as they made clear the safety he found in his relationship with Ono. The act of walking away from the Beatles' dizzying celebrity on "God" may have gotten the headlines, but Lennon ends up naming and then discarding all of his earlier talismans – only to follow with a quiet affirmation of his affection for Ono. As with so much of this cathartic, utterly remarkable project, even that came from a deeply honest place.

Listen to John Lennon Perform 'God'

"I just rolled into it," Lennon told Wenner of the towering conclusion to "God." "The first three or four just came out, whatever came out. I don't know when I realized I was putting down all these things I didn't believe in [...] Beatles was the final thing because it's like I no longer believe in myth, and Beatles is another myth. I don't believe in it. The dream's over. I'm not just talking about the Beatles is over, I'm talking about the generation thing. The dream's over, and I have personally got to get down to so-called reality."

Lennon would have bigger hit albums, and more culturally relevant songs. Plastic Ono Band, after all, has never gotten past gold-selling status – and "Mother" failed to crack the Top 40. Meanwhile, 1971's Imagine was a double-platinum smash, and home to an ageless title track; 1980's Double Fantasy eventually reached 3 million in sales after Lennon's untimely death. "Whatever Gets You Thru the Night" and "(Just Like) Starting Over" would both top the singles charts.

Still, Plastic Ono Band remains Lennon's most consistent, and most important, solo work. Every part of his convoluted genius – Utopian dreamer, angry brawler, lonesome orphan, naked provocateur – is found here, and it's laid bare inside the most stripped-down, revelatory setting of his solo career.

Lennon, in a talk with Playboy just before his murder, framed that legacy in a way that echoed this album's pitched struggle to loose itself from his former group, their time and their outsized fame. "I came up with 'Imagine,' 'Love,' and those Plastic Ono Band songs – they stand up to any songs that were written when I was a Beatle," Lennon said in 1980. "Now, it may take you 20 or 30 years to appreciate that; but the fact is, these songs are as good as any fucking stuff that was ever done."

Beatles Solo Albums Ranked

See John Lennon in Rock’s Craziest Conspiracy Theories

More From Ultimate Classic Rock