55 Years Ago: Bob Dylan Goes Rock With ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’

Bob Dylan's entire career has been filled with detours and left turns. He took his first -- and arguably the biggest -- on March 8, 1965, when he released the single, "Subterranean Homesick Blues."

It wasn't Dylan's initial foray into rock n' roll. In late 1962, he recorded "Mixed-Up Confusion" as his first single for Columbia. However, it was a commercial flop and his next records, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, The Times They Are A-Changin' and Another Side of Bob Dylan, were, like his self-titled debut, solo acoustic records.

Perhaps if “Mixed-Up Confusion” had been a hit, there wouldn’t have been a question of whether or not he had “betrayed” folk -- because the rock impulse was there all along. Still, those three albums found Dylan coming into his own as a songwriter, as well as a leading light on the burgeoning folk scene, for his insight into the civil rights and anti-war movements.

By January 1965, however, he was ready to give rock another try. Dylan and producer Tom Wilson returned to Columbia's New York Studios with a handful of session musicians. The resulting album, Bringing It all Back Home, was a tentative step in that direction. The second half almost entirely solo acoustic ("Mr. Tambourine Man" with Bruce Langhorne chiming on electric guitar), while the first half comprised of rock.

After Another Side saw Dylan move away from topical songwriting, Bringing It all Back Home was a return, and it kicked off with the wild ride of "Subterranean Homesick Blues." Borrowing from the title of Jack Kerouac’s novel The Subterraneans, the song was a beat poetry-inspired glimpse into the burgeoning counterculture set to the rapid-fire pace of Chuck Berry’s “Too Much Monkey Business.”

Listen to Chuck Berry’s ‘Too Much Monkey Business’

While Subterranean Homesick Blues" sounds like the hallucinogenic, surreal stream-of-consciousness lyrics Dylan would soon perfect, it’s relatively linear when the slang is deciphered.

The song's first two verses depict a scene of low-level drug dealers holding off the cops on the beat with bribes until they’re inevitably busted on orders from above. He polishes it off with the oft-quoted line, “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.” The lyric would later be co-opted as the inspiration for the name of the radical left-wing group the Weather Underground.

Over the second half, Dylan then ties it all into a larger comment about one’s options in society. You can follow the rules and maybe, after “20 years of schoolin’,” you wind up “on the day shift.” If you find yourself in trouble, there’s always the military as a way out. But regardless of which path you choose, you’re going to wind up as a mark, either for the “Girl by the whirlpool / Lookin’ for a new fool” or as a slave to the grind of middle-class life. The song ends with Dylan offering a third alternative, to “jump down a manhole,“ and join them underground.

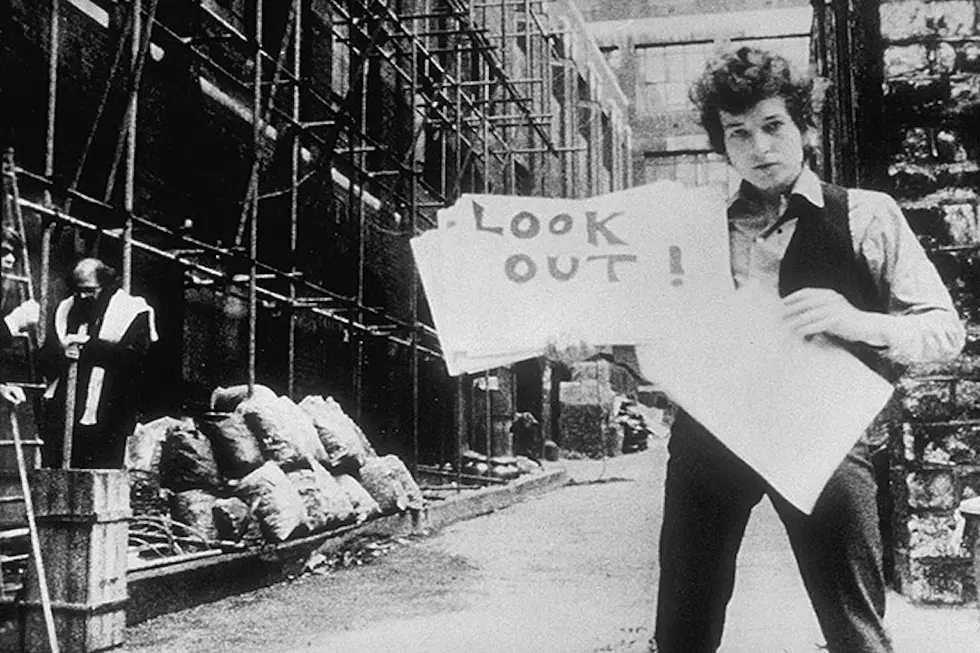

Watch Bob Dylan's 'Subterranean Homesick Blues' Clip

One of the reasons why the song has retained its relevance across the decades is its anti-establishment stance. Steer clear of the police, Dylan says, not just because we’re engaged in illegal activities, but because they think nothing of turning the fire hoses on innocent civil rights protestors. And who knows what’s really inside those parking meters anyway?

Musically, it was a unique take on the blues. Instead of the eight or 12 bars that are the standard for blues-based songs, Dylan needed 18 bars to cram in all the words in his verses. Bassist Bill Lee (filmmaker Spike Lee’s father) appears confused by the structure because he regularly loses his place in the song – and it didn’t help that Dylan started the last verse early in order to add a 19th bar. Still, this rawness and lack of precision gives the song its immediacy and shows how Dylan was building upon his influences by refusing to be confined by tradition.

Watch the Video for ‘Mediate’ by INXS

That spring, Dylan embarked on a solo tour on England. Joining him was director D.A. Pennebaker, who captured it in the documentary Don’t Look Back. For its opening, Pennebaker filmed a one-shot clip (embedded above) in the alley behind London’s Savoy Hotel, where Dylan held a series of cards with (more or less) a word or two from each of the song’s lines, dropping each one as it played. Over on the left, poet Allen Ginsburg and artist-songwriter Bob Neuwirth are talking to each other.

The video, which also served as the theatrical trailer for the movie, has taken on iconic status over the years. It has been the subject of numerous homages and parodies over the years, most notably INXS’ “Mediate,” which wound up in heavy rotation when added to the end of the video for their hit single “Need You Tonight.”

A less-famous, but more pointed, use of the video was by Tim Robbins in his 1992 mockumentary, Bob Roberts. The titular character, played by Robbins, was a singing Republican politician running for the U.S. Senate.

His songs espouse conservative values and denounce the left even as the music borrows heavily from leftist folk music (sample album titles: Times Are Changin’ Back and Bob on Bob). His “Wall Street Rap” is a yuppiefied update of “Subterranean.”

Bob Roberts was also the film debut of Tenacious D’s Jack Black, who first appears in a scene that mirrors one from Don’t Look Back.

Watch ‘Wall Street Rap’ from Bob Roberts

There have been a handful of cover versions of “Subterranean Homesick Blues” over the years.

Harry Nilsson gave it a try on his John Lennon-produced Pussy Cats, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers did too, in 1987. But those, and others, have lacked the power of the original. It could be that those musicians were too far removed from the scene that sparked it. Or maybe it’s just that, as a Columbia Records marketing campaign once said about him, nobody sings Dylan like Dylan.

“Subterranean Homesick Blues” was Dylan’s first charting single. While not a massive hit – it only reached No. 39 on the Billboard Hot 100 – it was enough to give Dylan what he wanted, an audience beyond the folk world. A few months later would see the release of “Like a Rolling Stone” and Highway 61 Revisited and even bigger fame. The major irony is that Bob Dylan became a hero on the strength of a song in which he clearly said, “Don’t follow leaders.”

Bob Dylan Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock