Billy Sheehan On The Winery Dogs, Touring With Van Halen + Working With Diamond Dave

Lest you fear that the rock band is an endangered species (and at times when you turn on the radio, it certainly can feel that way), the Winery Dogs are here to bring it back to the masses. Isn’t it appropriate that Billy Sheehan (Talas, Mr. Big, David Lee Roth), one of the baddest bass players known to man, is part of the mission?

Operating as a power trio in the grand tradition of any classic rock power trio you might want to name (okay, Cream, Rush, Grand Funk Railroad, ZZ Top -- you get the point), Sheehan is joined by drummer extraordinaire Mike Portnoy (ex-Dream Theater, Adrenaline Mob, Flying Colors) and his former Mr. Big bandmate Richie Kotzen on guitars and lead vocals.

Portnoy and Sheehan originally came together a few years ago to work on a project with guitarist/songwriter John Sykes. When things fizzled with Sykes, never really getting past the demo stage, radio personality Eddie Trunk suggested that Kotzen might be just what the doctor ordered.

And how. Kotzen is the surprise ace member of the Winery Dogs for anybody who hasn’t been following his solo work over the years -- a powerhouse singer whose stylings are reminiscent of vocalists like Chris Cornell and Sammy Hagar circa the ‘VOA’ period. With Kotzen in place, the trio quickly got down to business and knocked out their self-titled debut in short order.

The record is cohesively a great rock album from head to toe and offers plenty of the supreme musicianship that you might expect from these three. Individually and collectively, they all get their many moments in the sun to jam out at an energetically relentless pace that starts with the opening track “Elevate.” Over the course of the remaining 12 tracks, the disc's pacing rarely slows down.

The band is currently in the midst of their first full U.S. headlining tour and we grabbed Sheehan for a few moments to talk about how everything came together. We also spend some time digging through his record collection and talking about his moments sharing the stage with Van Halen, a dream which would eventually lead to a full-time gig with Roth’s solo band in a decadent lineup that also featured guitarist Steve Vai and drummer Gregg Bissonette.

Sheehan is one of those guys who has no shortage of things to talk about and it was really a pleasure to spend some time talking music with him. Thankfully, with the positive reception to the Winery Dogs album release (which charted in the Top 40 on the Billboard Album Charts), it would appear that these Dogs are probably going to stick around for a while --- and we of course had to ask what the plans look like for a second album.

I’ve heard all of the various things that you’ve done over the years, most recently your last solo album, 'Holy Cow!' What was it that made you want to get back into more of a band-type situation?

Well, I’ve always been a band guy. I held off doing solo stuff for years and years and years. When I finally did it, I kind of did it almost as a band, with drummer Ray Luzier -- we worked on stuff together. But I prefer working ensemble in a band situation. Solo artists, per se, I see a lot of solo records that are made and they seem to be so one-dimensional to me, because I like the interchange of ideas. I like when one idea gets modified by another [person].

For example, when I heard the Beatles’ ‘We Can Work It Out,’ I was really struck when I found out the lyrics McCartney was singing, “Try to see it my way/ Do I have to keep on talking/ Till I can't go on” and then [later] Lennon comes in and sings “Life is very short/ And there’s no time for fussing or fighting, my friend.”

The combination and song would not have worked unless you had [the explanation] of what’s really going to happen if we don’t get it together. That interchange of ideas between members and in bands, slugging through stuff and figuring it out and coming up with ideas, “Hey let’s do this” or “Hey how about this” -- I prefer that.

You can’t point out a better example than Lennon and McCartney of how important that dynamic is and the contrast.

I agree. In the case of the Winery Dogs, there’s not so much contrast, but there are certainly differences. But there’s also a thread of continuity and commonality to all of our histories that gives us a language to communicate with. Musically, we all have a sameness to some degree, but then we’ve all done different directions through our lives to give us some variety. So it worked out just right.

Was it easy to make the combination of everything that you’ve done collectively work in the context of this band?

It was an absolute breeze. All of us wanted to make a great record and we did it ourselves with no producer coming in and having him direct everything that would happen. We just did it ourselves in a room and I think that says a lot about how successful the interaction is. There were no arguments or screaming or furniture [being] smashed or anything like that. It was all real easy to come to conclusions and have an idea on how this chorus [should be] and here’s the lyric and it made it real, real easy. All of us really were pointed in the same direction.

Prior to getting together with Richie, I know that you guys worked initially with John Sykes. Did any of that material carry over or did you guys start fresh with the writing process?

Completely separate. That whole project was abandoned and gone and I played some simple bass on one or two demos of that and I don’t even know how that came out. I don’t think I ever even heard it back. So that was a completely different situation and utterly unrelated. With Richie we just started fresh and we didn’t even look back at all. We just thought “well, here it is -- this is going to work and we’re fine” and we got along fine [right from the] initial meeting and said, “Well, let’s go play.”

We went into a little room with a little drum kit, a little bass amp and a little guitar amp and started slugging it out. Within a couple of hours, we had the basis for about five songs that are on the record. It was real easy to put together and I love the idea of sitting in a room with small gear. [When] you’re set up [typically] with huge drums and amps and PA and monitors and stuff like that, you kind of get overwhelmed by all of the stuff.

Whereas if it’s just your hands, your heart and mind and your voice, you tend to [do better]. That’s the way to write. For me, when I write personally, I’ll just sit down just myself and a guitar. I’m not going to put together some tom loops and synth pads and keyboards. If you can illustrate a song by strumming it on a guitar or playing it on a piano and singing, that should tell you if there’s a song there or not. It always makes me laugh when people talk to me about their demos. “I gotta remix it” and they go “oh, I’ve got to do this and maybe add…” No, no, no -- if there’s a song, you can do it in a distorted little box with a guitar and voice and you should be able to hear it.

With that principle in place, we didn’t really need too much to illustrate when a song was born and when it did actually work. So it was an easy and enjoyable process, fun with a lot of laughs and the proof is in the pudding. In the end, people seem very pleased with this record, so that’s the basis for that, I believe.

Was there really a demo process, or were you looking at it as making songs at that point?

We did a couple of kind of demos and then we wanted the real drums in there later. The tiny kit sounded fine and it’s nice hearing Mike on a tiny kit, because it kind of concentrates everything he does down to a small kit and there’s an intensity to it, like taking plutonium and crushing it down into a little capsule. It’s quite a powerful little thing, you know?

Oh yeah.

So, even on the original kit, there was a bass drum, snare, floor tom and a couple of cymbals -- it sounded pretty good. But we decided, “Let’s do it up right” and Mike brought a full kit -- still not a big kit, but a full kit, mic'd-up properly to get the right representation of what he does and myself as well, I brought my actual gear in -- again, a small version -- and we laid it out that way.

Sonically, it was better and plus, once you’ve played the demo and listen to it, it’s almost like playing a song live in a way, because once you play it live a few times, it comes to life and you get ideas. So when we finally laid the things down for real, they had a life of their own already.

The way you guys started is probably a good place to start and it’s an important place, I would think. As a band, I don’t think you ever want to get too far away from that feeling of how it felt when you were with your first band, jamming in a room somewhere. That really maintains the integrity of where you started.

I agree 100 percent. To me, that’s the birth of almost every great band. You’re in a room and you’re playing together. I listen to old demos and bootlegs that I have of the Beatles and the Beach Boys and the Who and even Genesis and all kinds of bands. I’ve got an amazing collection of them [which captures the bands] in writing sessions or laying demos down all together in a room.

A lot of the Beatles stuff is those four guys in a room and they stop and they talk and all of the talking is on tape and they’re just sitting there hashing it out. To me, that’s the real traditional way of putting music together for an ensemble is to sit together and do it. I’ve done it all kinds of ways. You can always make it work if it comes to you in another fashion, but usually the way you make it work is by simulating the other way, so why not just do that?

You’ve worked with Richie in the past --- were you surprised to see how easily he fit into this slot? Obviously, you probably knew that he had the vocal goods --- but I think that’s been surprising to some people, just what a monster singer he is.

I have been an advocate of his for many years and I have always thought that he is a superstar undiscovered and I still think that. One of my goals in this band -- I don’t care about me -- I’ve had my day and then I’ve had another day and then I had yet another day, so I’m supremely fortunate. I’d just like to see the world discover Richie in a lot of ways -- that’s kind of my goal within this band, because I just think he’s a supreme talent and a wonderful guy and if the success comes, it couldn’t happen to a nicer guy.

Was the idea always to approach this as a power trio-type thing?

Yeah, I like the three-piece -- it’s great. Now that we’re on the road, it’s actually really paying off in a lot of ways in that it’s easier to watch two guys than watch three or four -- it’s way easier. Bass, guitar and drums, all watching each other and all singing, it leads to improvisation and successful improvisation where we make moves live each night in every song that we’ve never done before and it works.

We’re watching each other and we improvise and the songs come alive on tour and that’s an ideal situation for me. I love that you can do that. You don’t go so far from the original template that people don’t understand what the song is. You work within the boundaries of the foundation of the actual song but [when you] add in the ability to improvise and watch each other and make moves on the fly as we’re rolling and have them work, it’s a beautiful and extremely satisfying thing as a musician.

You don’t typically see a power trio that’s a bad live band, either. Power trios are an exciting prospect musically, both for the players and the audience -- it’s more locked in and there’s no room for any weak links, player-wise. Everybody has to deliver.

You’re exactly right. Grand Funk Railroad, ZZ Top -- some of the most famous trios -- and then most other bands were trios with lead singers and then you move into Led Zeppelin and the Who and all of that. But having the three guys is a really ideal situation.

That’s kind of how I grew up -- the original Talas was a three-piece and we played and sang very adventurous material for three guys. We did songs by bands with 10 guys in it and we pulled it off, you know? We figured out a way to do it. I love the trio and I love the power trio and it really allows everyone to stand out.

When you start adding a lot more guitars or keyboards in there, less is more to me sometimes in a mix. I go back to some of those early Grand Funk records and there isn’t even reverb or compression on those drums -- there’s just a mic, it goes to tape and it’s that drum and that’s all you hear. You don’t hear room or anything else -- no effects, [just] guitar, bass, drums and singing and those records sound amazing. They just sound huge and for an early ‘70s example of audio, I can’t think of a better example sometimes than Grand Funk. It’s the same thing with ZZ Top -- great guitar, awesome vocals, killin’ bass and drums, you couldn’t beat it.

I’m sure in that era, you had a lot of fun listening to those Grand Funk albums, Genesis, ZZ Top or whatever, dissecting how they were doing that.

Exactly, because that’s all we could do. There was no YouTube, no video, no nothing. You had to listen to it and try and figure out what the heck they were doing. That was a great challenge that leads you to become adventurous and builds up your investigative chops to the point where you can start to pull almost anything apart and figure it out.

I’m sad for musicians today where everything is on a silver platter. You know, they have a video showing you exactly how to play it and where you fingers go. We didn’t have any idea -- we’d end up doing stuff wrong -- it would be the right sounds, but we’re doing it incorrectly. That incorrect thing turns into a whole technique that didn’t exist before, so the ability to just listen to something, pull it apart and be able to duplicate it is a strong thing to have when you’re working on your own stuff. It all translates back to you -- that’s why I think the Beatles were such great writers, because they knew a million tunes and they had to sit down with the records and figure them out and figure out the lyrics.

I remember trying to figure out lyrics to songs, sometimes we had to kind of fake our way through something we didn’t understand. But now all of the lyrics are printed everywhere and there’s no mystery to it at all. It’s interesting.

Was there a particular album that you really locked in on, trying to figure it out from top to bottom?

Oh, many. My first three big records that I listened to over and over again and learned everything on them, were Jethro Tull’s ‘Stand Up,’ the first Santana album and the [self-titled] Blood, Sweat and Tears, with ‘Spinning Wheel’ on it. All three of them had brilliant stuff, brilliant lyrics and they turned into classic records as time went on. I had those three in particular at an early age, where I just went through them over and over again. I would play to that Santana record over and over and the same with Jethro Tull.

Then when Grand Funk came out and also, I got into the Who records in the same way where I would just put the record on and play along with it and figure it out until I had the whole thing down, front to back. It was a great lesson to learn. The young players come to me now and ask for my advice and I say, “Take three of your favorite records and learn ‘em top-to-bottom and be able to sit down and play them and sing them top-to-bottom and you will be a better writer, performer, singer and player in so many ways.”

It’s been a while since you’ve had the opportunity to debut an entire new band like this, playing a setlist that relies largely on a set of new music. It’s been interesting to talk with the members of Chickenfoot about doing a similar thing. What has the experience been like for you?

It’s a joy. I have a lot of people coming up that knew me through every incarnation of every band. I saw a guy last night that I went to grammar school with in Las Vegas. He lived in Buffalo back in the day. One of the original Talas crew members was out in Las Vegas as well and it was just great. It’s fun being out again and plus it’s always enjoyable to go out and hang with people after a show.

I do that a lot -- I come out from behind and the security guys get a little bit panicked and I go, “C’mon, everybody is our friends here -- I don’t know how many enemies are going to pay to come see me play!” So that’s a big part of it for me, just the hang and being able to put my thumb on the pulse of the public in general and see what they think and they feel. It’s always a good thing.

Then with the band, too - we have a good hang. We have a good bus and we have a good crew. It’s an enjoyable situation. If it’s a good bus -- because I hate flying so much, it’s such a pain in the neck -- with a good bus, I can stay out for months and months and months, no problem.

From playing these shows, is there anything you’re seeing from a reactionary standpoint as far as this material that moves the needle in an interesting way as far as where you might want to go with the next album?

Yeah. We see that people are responding to the jamminess of how we’re treating these songs. So I think we’ll always leave room for live experimentation when we lay something down, rather than write something that’s so tight that you’ve got to do it exactly like that in order to make that impression. With this one, we’ve got a little bit of room to move on everything and people seem to enjoy the band breathe life into stuff rather than just a copy of what’s on the record. We’ll probably continue in that fashion, I would imagine.

How productive were the album sessions for that first album? Did you record more beyond the songs that are on there?

No we didn’t. We did that and put it out there. Again, having no producer and doing it all ourselves, I’m glad we did it that way. Because a lot of times when you hear a record or you hear songs, was it the band that did this or was it the producer’s idea? [Laughs] You never really know and it kind of leaves a little hole in me wondering whether or not it was the band’s idea or somebody else or some outside writer’s idea. Love it or hate it, good or bad, everything on our record is exactly what we did and it was our ideas, myself, Mike and Richie. So to me, that really helped us build the foundation.

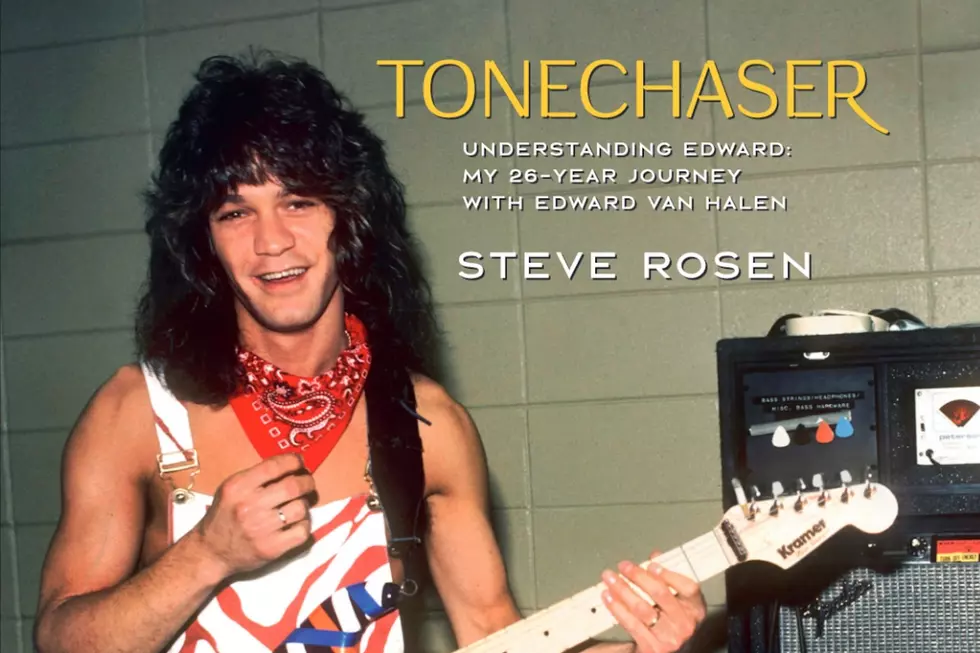

With Talas, you got the chance to tour with Van Halen a couple of times. What was the scene like at that time?

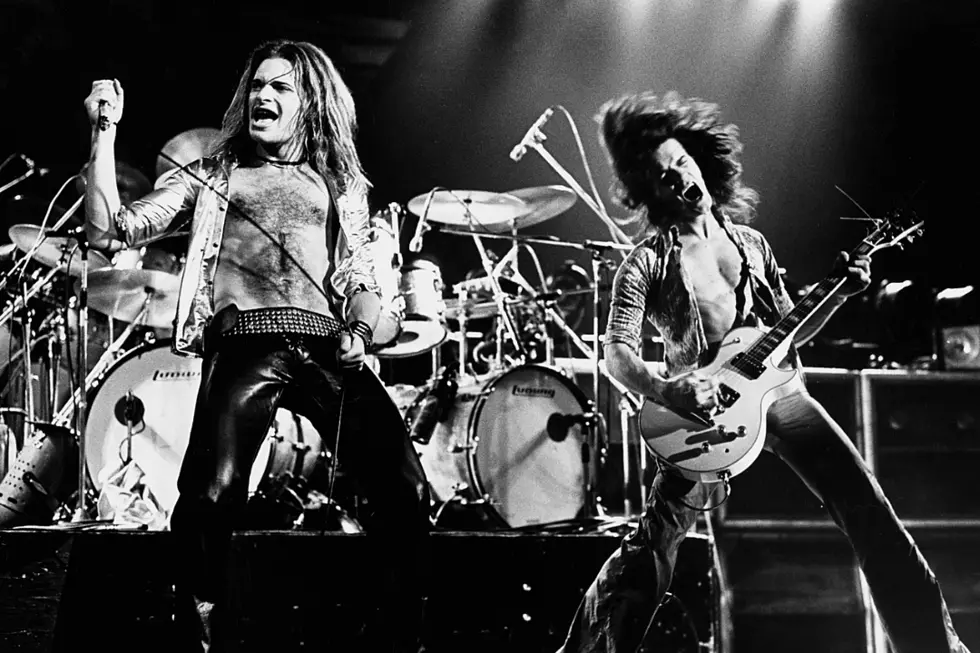

Van Halen was the greatest band in the world. At their worst, they were only spectacular. It was just an amazing experience. It was Showbiz 101 to see that band in action and behind the scenes and [to see] how incredibly precise and awesome [they were] and [with] almost military precision [how] they could get up on stage and make it look like it’s a big-ass party.

You know, to do a party, you just have a room with beer in it and have people in there. But if you do it right, it’s a riot and they always would do it right. And it would never seem like there was any effort put into it at all, but behind the scenes, there was great effort. The lighting, the sound and the cues and everything was all worked out, but when you watched it -- even though we watched it every night and it was the same every night, we’d still laugh at every joke. It was all worked out and scripted to a large degree, but boy, it was just done magically and perfectly.

A lot of that was Dave, of course -- he’s just a grandmaster of showbiz and the greatest frontman in my humble opinion that there ever was -- and still is. It was an incredible lesson to learn and they were very, very nice to us. They let us do some encores and they chose us personally to be on that tour, because they got a tape from Premier Talent, the booking agency. We had no idea we were even up for it until we finally found out, “Hey, you guys got the Van Halen tour” and we were like, “We got the what?” We didn’t even have a record out, really -- so we were very surprised. We made friends with everybody and I’m friends with all of them to this day, thankfully.

That was a band that was knocking a lot of people for a loop at the time. Particularly the bands that were touring with that band, it seems like if you’re in that position, that would cause you to take at least a second look at all areas of your process to make sure you had everything dialed in.

Yeah, when you’re up on that stage and it’s Van Halen’s stage, you’re under a microscope and there’s a whole lotta people watching. We got lucky. We scored and we got a bunch of encores and we did real well and they were real pleased with us. I created a relationship there that, of course, led to the Dave thing later.

It was a little spooky though, getting up on a stage like that in front of all of those people and telling them that we’ve never played there before and we had no record out and we just gotta go up there and do it. There again, we get back to the power trio thing and with everybody singing and playing, we got up there and did our thing and they responded positively. Sometimes you roll the dice and the sun comes up.

One of our readers wanted to ask about how you were asked to join Van Halen quite a few times. It’s surprising that never panned out or went that way.

Yeah, in the end I’m not really sure what the purpose of any talks with me to join the band was. But it happened a couple of times. I love Michael Anthony and I felt totally torn, because I love the band too -- I didn’t want to see the band change and [have them] bring some new guy in, even if it was me. I’m a real believer in the original lineup -- I love that concept as a fan. Whenever anybody changes, even if it’s some peripheral person, it’s kind of not the same to me -- once in a while, it works. So I was torn a little bit, but it never really panned out.

In a way, nature took its course. When Dave left, he called me and we started that band and that was close enough. I always said when I was in Buffalo, the only band I’d ever leave Talas for was Van Halen and when Dave called, I said, “Okay, close enough, I’m gone.” That was it!

That ‘Eat ‘Em and Smile’ lineup, as it’s now called, that was a supergroup to end all supergroups. Even now when you look at some of the combinations have come along since then, that lineup remains impressive. The albums that you guys made speak well of what was accomplished. Was there instantly good chemistry when the band came together to work with Roth?

Absolutely. ‘Eat ‘Em and Smile’ was just a great experience for all of us. We would hang in the basement with Dave and tell stories. He had a whole garage full of beer left over from the US Festival. He lives in Pasadena where it’s pretty hot and the garage, of course, was air-conditioned, so the beer was skunked by then.

But we drank it anyway -- we’d sit around and drink skunk beer, like we were sitting around the campfire in Dave’s basement, telling stories and hanging, me, Steve, Gregg and Dave. It was a riot. On tour too, we just had a complete blast.

With ‘Skyscraper,’ things changed. I think it was more management-run at that point, which I think was a mistake in retrospect. It wasn’t as personal and fun or close or [us] hanging out. But the ‘Eat ‘Em and Smile’ thing was just an incredible experience. Everywhere I go, someone has an ‘Eat ‘Em and Smile’ record for me to sign. Coming out of the jungles of Indonesia, somebody has a copy of it and it’s incredible.

Ted Templeman produced that album while Roth and Vai end up producing the next one. How much did that change the dynamic of the sessions for that second record?

Quite a bit. The second record was done one at a time. We never played together as a band ever. The drums were laid down, I came in and did bass and then they did a zillion guitar overdubs and it wasn’t the band playing. ‘Eat ‘Em and Smile,’ Ted had us all in a room and we were playing, we laid down the track and there it was.

I remember even Steve wanted to go back and double all of his guitar lines and Ted said “no, let’s just leave it organic the way it is and leave it there” and I’m glad he did, because it really showed a side of Steve’s playing that I don’t often see now where he’s just kind of on his own and he’s just gotta play. He’s a studio wizard, so when he goes in the studio he ends up with a lot of wizardry and it’s brilliant and beautiful, but what he did on ‘Eat ‘Em and Smile’ is a different character than the Steve I see today.

I love ‘em both, but I’d love to see Steve go out now with a combo amp and a drummer and a bass player and do a record like that without going and doing a zillion things after. A lot of players are like that and they approach it differently -- Steve uses the studio as an instrument now and on ‘Eat ‘Em and Smile’ he didn’t have the opportunity because someone else was in charge. Then on ‘Skyscraper,’ the record sounds a little over-produced to me and it was not one of my favorite records.

It was even years before I actually listened to the whole thing because I’d left right at the end of making that, so it was not my favorite time, music-wise and career-wise, because unfortunately I had to make a move and I did. It’s always a sad thing when you have to leave or break something up or make a change like that. But unfortunately, that’s what had to happen.

More From Ultimate Classic Rock