How the SoundScan Era Rocked the Music Industry

In 1991, a gargantuan shift occurred in popular music. No, it didn’t smell like Teen Spirit. And, no, it wasn’t an album that could be “none more black” (though both Nirvana and Metallica would ride the wave of this watershed moment). It actually had nothing to do one specific artist at all.

On May 25, 1991, Billboard made a change to the Billboard 200 Top Albums, when the magazine began using SoundScan data to tabulate the positions on the top albums chart. After decades of gathering numbers via a flawed honor system, the industry leader in deciding what was “popular” in popular music started employing accurate sales reports.

Woo! Accuracy! What’s more rock ’n’ roll than that?

Actually, not much. SoundScan’s data collection returned the power to the people, the genuine fans who buy and listen to music. Twenty-five years ago, the firm started counting how Joe Music Fan was spending his bucks, instead of listening to a record store manager’s easily corrupted opinion.

It turned out that people were buying a lot more metal, hip-hop, country, R&B and alternative rock albums than the old system claimed. The change on the charts was immediate. The change in the industry was almost as fast. Artists that had been relegated to their genre pools (from Nirvana to Ice Cube to Garth Brooks) were now free to swim in the mainstream.

SoundScan not only altered the music landscape of the early ’90s, it completely changed how music, albums, artists and songs would forever be perceived, managed, promoted and heard. It changed everything, but to understand how much, we have to go back to the days before the SoundScan era.

Billboard began publishing a chart of the top albums in 1945. It had gone through many permutations and names over the years, based on the rising popularity of the LP and numerous shifts in the music industry. But before 1991, one thing stayed the same: the method for determining the chart positions. The magazine used a survey method, in which staff members called record stores and retail outlets all over the U.S. and took the managers’ word on what had been selling during the past week.

At best, the system was flawed. A clerk could have a bad memory or a bias for or against certain artists. Some managers likely skewed their answers based on what stock they had and the money they could make. (If you’ve got dozens of unsold copies of Slippery When Wet in the racks, why not claim that’s the best-seller?) In addition, the stores would omit so-called genre albums – country, alternative, hip-hop, metal – when it came to reporting for the overall album chart, even if those discs had outsold mainstream pop albums.

At worst, the methods were susceptible to fraud. Record label representatives “encouraged” store clerks to over-report sales to Billboard by visiting with armloads of gifts. It was another form of payola.

“In the past, the major labels gave away refrigerators and microwaves to retailers in exchange for store reports,” Tom Silverman, then the chairman of the Tommy Boy indie label, told the New York Times in 1992. The allegations weren’t sour grapes from an indie guy who couldn’t compete. In the same article, the president of Tower Records confirmed the practice among his employees, despite decrying it.

Even though Billboard claimed it would cease taking figures from anyone who was obviously juicing the numbers, the system relied on good faith. In the era before the omnipresence of computers, it was the best method possible. But in the ’80s, perhaps the only thing changing faster than the volatile music industry was technology.

Watch Nirvana's Video for 'Smells Like Teen Spirit'

Four years before Billboard partnered with SoundScan, another partnership began. In 1987, radio and record industry veteran Mike Shalett joined research analyst Mike Fine to start Sound Data, a firm that would report on the music-buying habits of Americans to subscribers – such as record companies, radio stations and MTV. By 1989, the two Mikes were discussing the ability to tabulate nationwide record sales via computerized sales reports.

“The TV and movie and clothing and grocery industries have taken this kind of information for granted for years,” Fine told the Los Angeles Times in 1991. “We realized that there had never been an accurate method in the music business to track actual sales and we figured the time was ripe for change.”

The change that Shalett and Fine envisioned would swap hype for hard data. The new system would work like this: SoundScan pays record stores and other retailers a small fee for keeping a weekly tally of the actual products sold each week. Because a computer program keeps a count of individual records, tapes and CDs based on the specific bar codes that get scanned by store registers, there’s little room for error, bias or fraud. SoundScan gathers all of the information and then sells it to a league of subscribers – anyone with a vested interest in knowing the music-buying habits of the American public.

The major recording labels were the target clients for this service, but none of them jumped at the opportunity to sign on with SoundScan. When Shalett and Fine made their proposals to the record companies in 1990, the bigwigs didn’t think such specific consumer information was worth the hefty subscription fee ($800,000 for each major music label). However, the folks at Billboard – which had been toying with a new and improved system for the magazine’s vaunted music charts – decided that SoundScan was a better option. Billboard and SoundScan made a deal in March 1991.

When the first Billboard album charts to use SoundScan data debuted in May, a panic rocked the music industry. The heads of major labels furiously claimed that the system had been rolled out too quickly, it over-represented the Southwest at the expense of the Northeast and it didn’t include enough mom-and-pop record shops. Many pointed to the lack of data from Tower Records, then the nation’s No. 2 music retailer, which was not reporting to SoundScan due to incompatibility between computer systems.

Although the claims were factual, many suspected the uproar was caused by something deeper. For years and years, the major labels had known how to “game” the system to their financial advantage. Suddenly, all of the tried-and-true methods went out the window. No one knew what to do in the face of albums suddenly skyrocketing up the chart (compared to the slow climb of the past) or hip-hop and metal albums landing in the top position (both N.W.A and Skid Row sat atop the Billboard 200 in the first month of the SoundScan era).

The record execs kicked and screamed. SoundScan addressed concerns by incorporating some Tower Records locations, as well as many more independent music stores. Within months, all of the major labels agreed to SoundScan’s fee in order to get the detailed sales information for themselves. By November, Billboard had adopted SoundScan’s data for its singles chart (the Hot 100) as well.

The industry had changed, and no one wanted to be left behind.

Watch Metallica's Video for 'Enter Sandman'

Essentially, the labels had no choice but to buy in, because of how rapidly the industry transformed at the beginning of the SoundScan era. It wasn’t like Brooks or Metallica became popular overnight. Each had a significant fan base pre-SoundScan, but the new methods allowed other music fans to see how popular these acts truly were.

Popularity begets popularity. If an album’s doing well, people will check it out and see what the fuss is about. In addition, these artists from “minor” genres were transformed by the record labels themselves. The major record companies began to throw tons of promotion money into acts that they recently discovered could compete in the mainstream. The 1991 end-of-year Billboard charts bear this out, with two albums by Brooks, and Metallica’s Black Album sitting among records by Natalie Cole and Michael Bolton.

The best example of the changing musical landscape forged by SoundScan is Nirvana and the band’s blockbuster album Nevermind. Would it have been a blockbuster before SoundScan? A 1992 article in Spin magazine deemed a No. 1 album by Nirvana “unthinkable” before the new era, suggesting that the “charts don’t just report tastes; they amplify and shape them.”

Here’s how it happened: Nevermind and its accompanying lead single, “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” come out a few months after Billboard publishes its first SoundScan chart. Buzz builds on alternative radio, around the Nirvana tour and within the industry, which results in decent album sales, which are now accurately reported on the Billboard chart. Others, like MTV and mainstream rock radio, begin to take notice of the numbers. They start playing Nirvana. More fans hear “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” Metalheads come around. Old guys who haven’t bought an album in 10 years get interested. Pop fans embrace Nirvana. Requests to radio go way up. Sales take a huge jump. In only a few months, the alt-rock underdogs dethrone the King of Pop on the top of the Billboard 200.

Nevermind has been called a game-changer. It was. It is. But it probably doesn’t get close to being a landmark album without the industry game-changer of SoundScan.

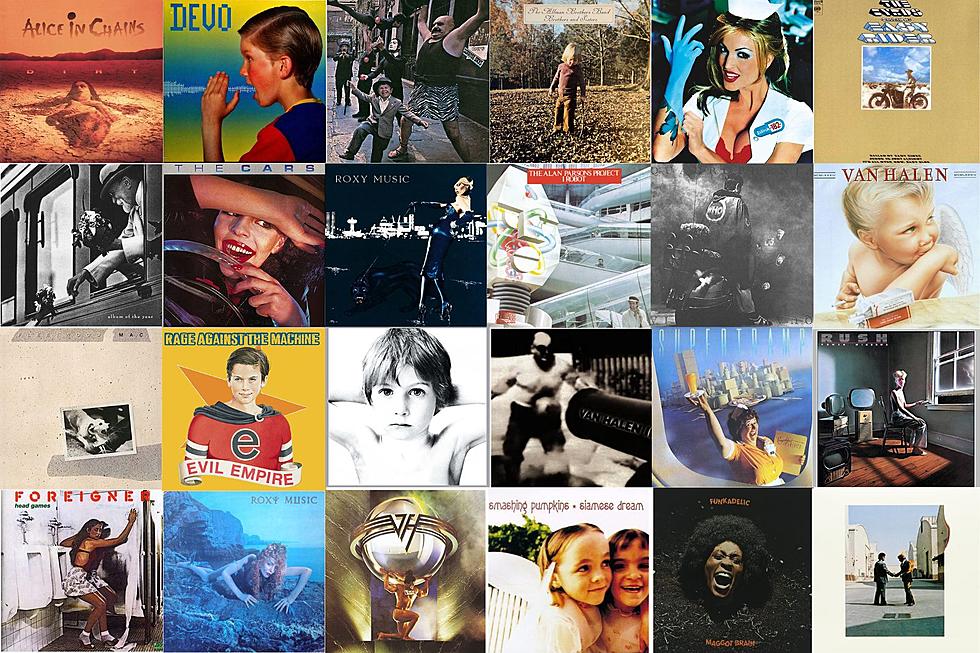

SoundScan allowed Nirvana to become one of the biggest acts in the country (and then the world). But Nevermind was only the beginning. Over the next few years, an unprecedented number of hard rock albums topped the Billboard 200, including discs by Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, the Black Crowes, Pantera, Alice in Chains, Stone Temple Pilots and even Aerosmith (with their first No. 1 album). What had been the alternative to mainstream music had become the new mainstream, and we’re not just talking alternative rock here.

The early ’90s saw the beginning of country and hip-hop as mainstream musical forces. Fans were buying Tim McGraw and Snoop Doggy Dog records in huge numbers and SoundScan/Billboard proved it to be true. Decades later, those two genres have proven consistently commercially resilient, even in an era when millions of fans have stopped buying albums.

SoundScan turned out to be just as irrepressible. What is now known as Nielsen SoundScan (the TV ratings giant acquired SoundScan a few years after it debuted) has continually adapted to suit a rapidly shifting music industry. For instance, in 2003, it began tracking downloaded music and factoring the numbers into the charts. Pretty soon, more fans would be downloading singles and albums than purchasing physical copies in stores.

Nielsen SoundScan made an even bigger change in December 2014, when it completely altered its method for tabulating the Billboard 200 (a chart that had been witness to an enormous drop in sales over the past decade). SoundScan announced that it would incorporate on-demand streaming data into the weekly tally of best-selling albums. Under the new system (currently in place), 1,500 song streams on a service such as Spotify or Beats Music is equal to one album sale on the Billboard chart. In addition, to match the market’s preference towards singles, 10 digital track sales (even if they are all the same song) are now equivalent to one album sale.

Although the move appears forward-thinking in an industry where streaming is becoming the method of choice for many listeners, some find it strange that a system originally created to track actual album sales numbers is now counting unpaid streaming as “sales.”

Good or bad, right or wrong, SoundScan has made a lasting imprint on the music industry and the artists it helped legitimize in the eyes of record companies, radio stations and fans. It’s only fitting that the best-selling album of the SoundScan era belongs to one of the first bands affected by 1991’s epic shift. Enter Metallica’s Metallica, with more than 16 million copies sold. And true to SoundScan’s original intent, most of those Black Albums were actual copies scanned with an actual bar code in an actual store.

Top 30 Grunge Albums

What Classic Rockers Said About Grunge

More From Ultimate Classic Rock