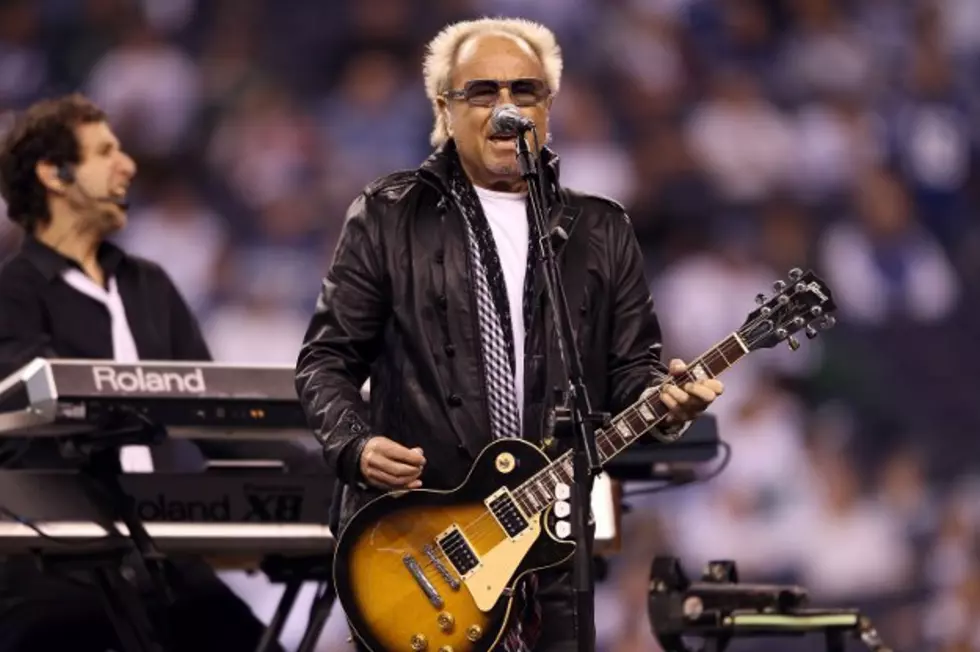

Foreigner’s Mick Jones Recounts ‘Crazy S—‘ He Went Through with Van Halen

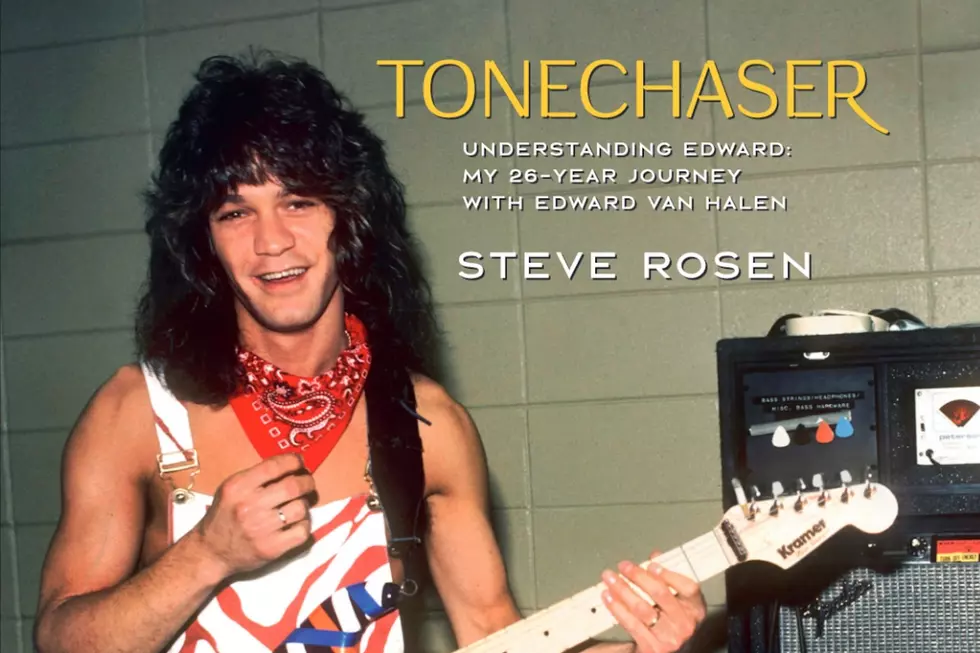

Mick Jones is best know for his many years as the guitarist and songwriter in Foreigner, but he's also a notable producer who has twirled the knobs for both Billy Joel and Van Halen. He produced the latter's pivotal '5150' album, their first effort after replacing original lead singer David Lee Roth with Sammy Hagar.

Talking to UCR about his upcoming induction in the Songwriters Hall of Fame with former Foreigner vocalist Lou Gramm, Jones also took a moment to share some of his wild stories from those sessions, which he says were eye-opening even by rock and roll standards.

How did your songwriting style inform what you would do as a producer, working with Van Halen and Billy Joel?

Well, I think that was probably the main reason that they approached me in the first place was the fact that they knew I was a writer. They knew I’d had some success as a writer and that was my calling card really. When you’re writing and preparing an album, that’s the most important part and being able to be objective. You know, coming in from the outside, having not been involved in the thought process in the beginning and being able to take an objective look and listen to what was going on. They gave me the ability to help with trying outside ideas and suggestions that I would have and they had a certain respect for me because I had a certain pedigree already.

It’s tough when you’re working with somebody and they ask you what you think and you’re truthful, you say, “Well, I think that it’s weak in that area right there,” and they go, “What do you mean? That’s the best part of the song!” And I said, “Well, you’re asking me for my opinion so take it. I don’t think that’s going to fly,” or “This could be better here.” I’d have a few suggestions sometimes. I didn’t go in too much to writing anything with them, because in both circumstances, Eddie [Van Halen], he knew what he wanted to do. And Billy was a formidable songwriter to start with, so going in and critiquing him, I had to summon up a bit of strength there to face doing that. But it worked very well.

I remember on the song ‘We Didn’t Start the Fire,’ that kind of started out as a country song, I think it was called ‘Jolene’ or something, even. I said to Billy, “This song sounds so familiar, it sounds like a Dolly Parton song,” and he said “What?” He got really pissed and he locked himself away in a room with like a Time-Life Almanac of historical events since his date of birth and that’s where he came up with the lyrics. He walked proudly back into the studio and said, “Well, take a look at this one.” And I said, “Well, that’s more like it!”

So you had to take chances that people would take offense sometimes. To me, a real producer has to have the balls to do that, to be able to have that vision of what the end product is going to be like and help guide the artist or the band towards that. That’s what I’ve tried to do, and I’ve tried to do that with Foreigner. But I’ve always tried to bring in a second or third ear to keep my perspective and balance it. I think it’s important to have that.

Walking into the Van Halen situation, what was that like? Because obviously, they had working up until that point with Ted Templeman for all of the previous records. Besides knowing you as a songwriter, how comfortable was that to walk into that situation where you were the new guy?

I go a long way back with Sammy Hagar, since he was in Montrose. He picked me up at the hotel and we were driving up to Eddie’s studio and we were talking about the old days and finally he said, “I’ve got to tell you Mick, all of that was wild and crazy and all of that sort of thing,” but he said, “We are just about to walk into another dimension of that.” [Laughs] And I said, “What?”

He said, “I wasn’t going to tell you earlier, but you’d better get ready for some crazy sh– now.” I went, “Whoa . . . ” and I’d been around and seen a lot, you know. But it was pretty crazy up there. It lived up to its title. It was a challenge, because they had a lot of the stuff that they had been writing and it was a new writing partnership with Sammy and Eddie and they were just coming down from the split with David Lee Roth. It was a big time . . . a lot of different things were happening and a lot of emotions were flying around. It was kind of exciting [but] it was [also] scary, thinking, ‘Well, what can I do for this band?’

As you said, Ted Templeman had done all of the albums up to that point, and Donn Landee was the engineer who was running Eddie’s studio and he’d done every album they had done and here was I, walking in from a completely different place in a way and stepping in [with a] “Who’s this guy?” kind of thing. I got that feeling at the beginning from Donn Landee. He wasn’t particularly thrilled to see me, I don’t think. Granted, I got into the thing and I started to really listen to the songs, and I helped with the arrangements and I helped with the structure of the songs, and I worked a lot with Sammy on his vocals.

I think that’s if anything, one of my specialties in production is working with vocalists. I was able to bring him up to where he needed to be to front that band. We went through some crazy times. The engineer locked himself in the studio for a day and threatened to burn the tapes. It was a real standoff, you know? It was touch and go whether the tapes were going to survive. It all ended up great and everybody ended up [being] really cool and happy with what had happened, but it was pretty exhausting. It all paid off in the end.

Did your influence help on some of the tracks like ‘Love Walks In’ or ‘Dreams’ that were on the power ballad territory side of things that they hadn’t done before?

Yeah, I worked a lot on the arrangements and the vocal performances and helping [them] just to find the melodies a bit, especially on ‘Dreams’ and ‘Love Walks In.’ I put my advice and my suggestions in where I felt they merited them. I don’t know if you could have gone in with an approach of, “Oh, I want to change all of this,” which I think would have been disastrous. But I worked on the sound quite a bit with and eventually ended up being good friends with Donn Landee, who is a great engineer.

I think we improved the sound of the drums for example. I think it’s probably one of the best sounds that they’ve had on an album, on that album. And as I said, [I focused on] just using my suggestions where I thought they were needed and useful, not trying to just sit there and constantly coming out with ideas. I think it was a balance of letting the band do its thing and then just putting the glue in there a bit to make it coherent and to make it as good as it could be.

More From Ultimate Classic Rock