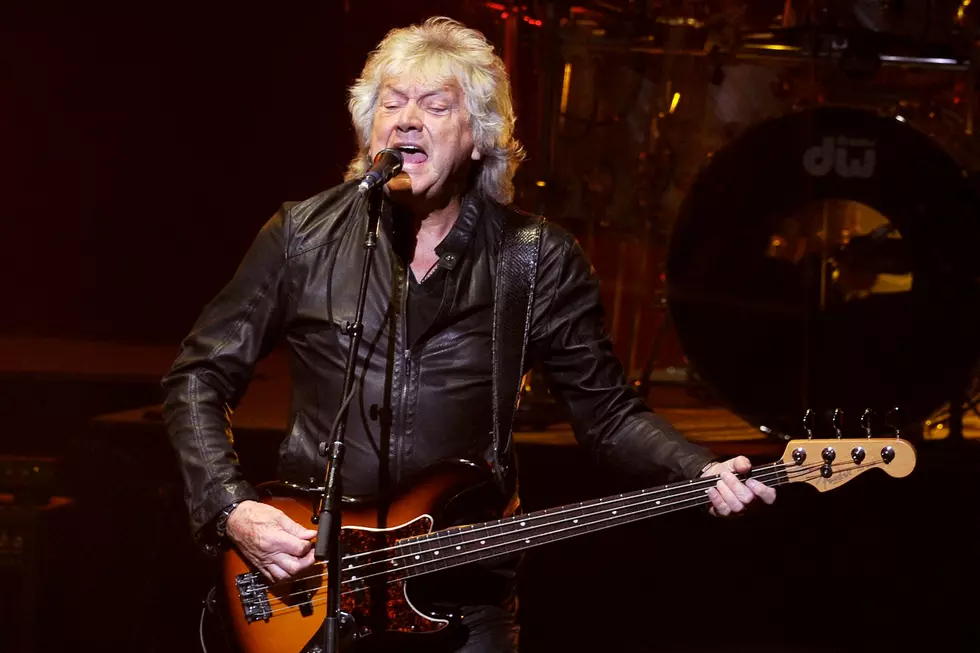

Justin Hayward On His New Solo Album And Possible New Music From The Moody Blues

For Moody Blues frontman Justin Hayward, the future has become the present and certainly, many days have passed since he first joined the group nearly a half-century ago.

While the band remains popular on the touring circuit performing dates annually which take them all over the world, it's been a while since there has been new music from the Moodies -- their last album was 'Strange Times' in 1999.

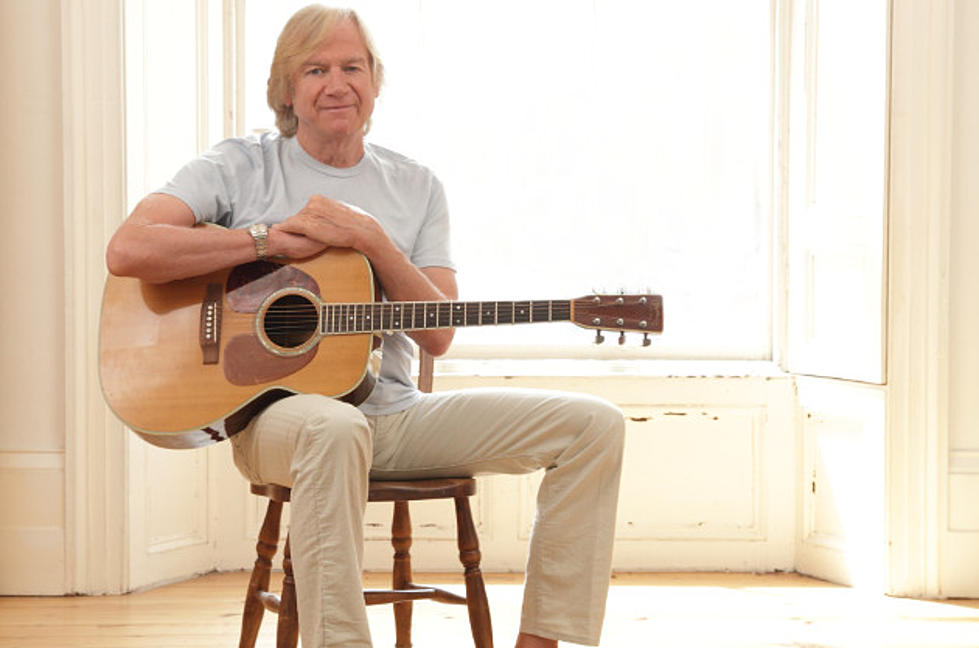

Hayward is providing some relief for that drought with the release of his new solo album 'Spirits Of The Western Sky,' which finds the veteran singer/songwriter musically in familiar territory and also pushing onward into new horizons with three songs that venture into the country/bluegrass genre.

Hayward spoke with us recently to talk about the new album and also, the possibility of new music from the Moody Blues.

Your solo albums have always sounded just like that. Having heard the ones you’ve done over the years, they’ve always felt more individual than what you were doing with the Moody Blues and a lot of times, a bit more stripped back. For you, where’s the separating line between the two?

You know, I started collecting material only about three or four years ago for this record, but it included stuff that I’d written up to 12 and 13 years ago. And I thought about that, "Now why didn’t I put a couple of these songs towards the Moody Blues things that we’d done," and I thought, "Well, maybe it’s just too personal. Maybe I’m able to say things from just me, from my own voice, than I would expect a band to share and sentiments."

I think that’s probably what it is -- that’s probably the difference. I think this album is probably more from my heart about relationships and peoples and things like that. And I must say, I did do a few other tracks that I haven’t used that were more social comment [based].

But in the end, I thought I didn’t really have the right to say that kind of stuff or talk about the world. Really, what I have the right to do is to talk about my own relationships and my own feelings and stuff like that. So I suppose it just comes from what you think is right for me to say and what I think is right for the group to say.

Those other tracks that you mentioned that you didn’t use, where is the right place for tracks like that?

I don’t know, because often the demos that I do, I think if there was a Moodies record coming along, I’d have to start from scratch and not use stuff and think, “Oh, I’ve got this track that I’ve already virtually finished, but haven’t mixed or messed around with.” So I don’t know, and at the moment, I think, even the label is kind of liking the bluegrass things that I did [on the new album] and seeing that as a great direction.

Nashville has been so welcoming to me over the years and it was such a thrill to do those [songs]. But still, the heart of this album is the personal songs that I’ve written and the things that I recorded with Alberto [Parodi], my co-producer on this. So it’s a mixture of all of those things.

I know you’ve been working on this record for a few years now. What really was the spark that got you working towards doing another solo record?

I was doing some mastering for Universal for the 5.1 surround sound versions of the early Moodies stuff and I just couldn’t see a Moodies album coming up or looming on the horizon. I think that the Moodies is in such a lovely place where actually, we’re rediscovering the vast catalog that we have and getting to know and reacquainting ourselves with songs that we only ever played for a couple of days.

Like, we do a song in the set now that’s called ‘You and Me.’ I think we must have spent two or three days on it, back when it was recorded in the early ‘70s and then you just forget about these songs, but the fans never forget about them.

So I think the Moodies are rediscovering our own catalog and trying to bring it to the stage and bring it to attention. I thought that the place really for my new songs was in this solo album and Eagle Rock had given me that opportunity, which is really wonderful. I’m very grateful to them. They’re a great company and I’m very pleased that they should take an interest in it.

You mentioned the country material -- I listen to this album and I hear it move through some interesting phases and it seems like you did some specific sequencing work in that regard. Am I hearing that right?

Yeah, I did. Because I tried scattering the three bluegrass things through the album and it just didn’t sound right. It sounded like we were all off to Nashville in the car and then we were back in Europe somewhere three minutes later. So I put them together and I think it works best like that. Once you step into Tennessee, you should stay there for a while.

What pushed you towards that Tennessee sound?

Well, I was invited there by a songwriter’s association back in the ‘90s to be part of a small live showcase, only doing three or four songs each. And it was me, Stevie Winwood, who was living there then, Michael McDonald, Jimmy Webb, who I worshipped, you know? I was like, “Bloody hell, it’s Jimmy Webb!” There were all of these people and I realized how welcomed I was there as a songwriter. Not anything else -- just as a guy who wrote songs, because that’s what they love. And also, we all know that the most valuable commodity in the pop music world is youth, really.

But in Nashville, it’s not -- they look up to you if you’ve had a lot of experience. So I got to know people there and went back and did a few other showcases in just a few clubs and things, with country artists and my stuff seemed to fit into that genre. I kept in touch and then there was an album that came out that was a tribute to the Moodies -- it’s called ‘Moody Bluegrass’ and that really kind of turned me on and I got to know the producer who did that and a couple of the musicians. I just thought it was the perfect...it was like playing when I was a kid, where you bring your instruments and it sounds [like you're] right in your front room or in what they call a parlor or something.

Bluegrass, I loved the fact that there was real rules about it -- there was no drums -- you don’t have to worry about drum spill on all of the microphones. There’s no electric bass, you don’t have to fiddle around with Pro Tools or anything and [there’s] no electric guitars.

The fact that we could just play, a small group sitting there and looking at each other, doing the vocal as well and at the end of it, they’d say “do you like it?” or “we could do it again if you want to.” You could do three tracks in an afternoon -- it was just sensational. I was really drawn to it and I’m sure I’ll do it again.

You’ve got a song on here that you wrote with Kenny Loggins. How far back do you go with Kenny?

[He’s] an acquaintance. I wouldn’t say a real friend -- but he is now. [But prior that that I knew him] as an acquaintance. I think we had people in common from the Poco days. We did a tour with Poco in the ‘60s and Jim Messina and through that, I was an acquaintance of Kenny’s. And then we were in the same hotel in Albuquerque three or four years ago and he had a day off and we were working and then we had a day off in the same hotel and he was working.

He really drew me into it. He knew how to co-write -- I’d never really been comfortable with how to do it. He made it real easy and I just started fiddling around on the guitar and he said, “I like that” and he’d play it and expand on it and we had just a great afternoon and that song ['On The Road To Love'] came out of it. The whole of that song came out of it and then I did a demo of it, I sent it to him [and] he sent it back to me with some great vocals on it and some great guitar on it and then just backwards and forwards, we worked on it and I had done nothing with it.

It was only about six months ago that I wrote to him and I said, “Listen, I’d really like to finish that song” and he said, “Great, go ahead and do it.” I did the lead vocal and he did all of the backing vocals and his vocal harmonies are right on. He doesn’t need to do anything twice or fiddle around with it. It was just a real pleasure. I’m very glad that it’s turned into more than an acquaintance.

‘Lazy Afternoon’ is one of my favorites from the new album. Can you share the story of how that one came together?

I’ve got a small apartment where I keep my stuff and another small apartment where I live. I was imagining that I was in a garden of my childhood and things that happened to me and every time that I sat down on the keyboard and played. I just had those first few lines and the first verse and every time I sat down and listened to it, it took me back to a place. I wasn’t in my little flat anymore; I was in this beautiful garden, wondering what on earth....I remember the circumstances as well, of being very close to somebody and then wondering why they chose a particular path. I hope that comes out in the song. I was never quite sure whether that came out in the song. It’s got a kind of bittersweet thing in it as well. Maybe it does.

This album to me sounds a little bit more built up than some of your previous solo stuff that I’ve heard. Do you think that the lack of a new Moody Blues studio album pushed you into going a little bit further with some of these songs than you might have gone otherwise?

Yeah, I think so, [as far as] taking a few risks and saying things that I maybe would not have been able to say on a Moodies record.

Now that you’ve finished this album, where does that put you as far as the possibility of doing another Moodies album? Do you still see that somewhere in the distance?

I do. I know that we did get a little disillusioned with stuff, but I still think something is on the horizon. It’s just that we have to go do other things first. The Moodies is a responsibility to deliver the goods every night onstage and to do it sincerely, otherwise it doesn’t work. You’ve got the three guys left in the Moodies that really want to do it onstage, so I think we’re truer to the old records now than we ever were.

But what the future [holds for] the group as a recording unit, I just don’t know. I can see it, as a DVD and a live thing, but I don’t know what’s going to happen. It didn’t push me in this direction, but I just ended up with so much material that I felt a duty to myself.

You know, I feel a duty to write because I can write songs. So I felt a duty to put these things together and include them in an album, just even for my own and Alberto’s sake and even for my family’s sake, really.

Listening to your albums, whether they are solo or Moodies albums, I’m just always interested to see how that is going to affect artistically where you go with the next project that you do.

I’m drawn to Nashville again. Whether that will be the right thing to do, I haven’t quite decided. I’m kind of grieving for the studio again. [Laughs] I already want to get back there and have those feelings again. But in the meantime, the Moodies are on the road and there’s some pressure for me to showcase things and do things on the road, so I’m just going to see how it pans out this year.

There’s quite a lot of Moodies work, but the most important thing in my life at the moment is ‘Spirits of the Western Sky,’ because I know what it means to me and how I always live somewhere where I can see the western sky and my heroes were always in that western sky.

When me and my brother were little kids, we had a room at the back of our house and our parents were both teachers and they were just out a lot. So a lot of the time it was just me and my brother. We could just see this vast western sky and I was born in the west country of England. We could see the weather coming and we used to play records and 45s and think that Buddy Holly was out there in that western sky and the Everly [Brothers] and Nat King Cole and Bill Haley.

It was just fantastic, so it triggered something. So at the moment, I’m hung up still on that spirit. I’ll have to look somewhere else I think, to move on from here. I’m not quite sure how I’ll do that. Like I said, social comment is more appropriate for the Moodies than it is for me, but I’m not sure we have the right to do that. So I’m going to have to put a lot of thought into where I go from here.

There’s a version of ‘I Know You’re Out There Somewhere’ on this album. How did that come about?

Well, I was put in touch with a couple of Swedish guys who really loved the song and wanted to do it and could see this dance version of it. They told me that they had looked at sampling the original Moodies record, but they couldn’t take from the Moodies record -- it was a mess when they tried to use the Moodies record, because they couldn’t get the voice out and they wanted my old DX7 that I played on it and a couple of other sort of twiddly bits and they couldn’t isolate them from the recording, so they just suggested it.

They said that they wanted to do it and if I had the time, would I be up for doing the particular bits that they wanted? They were very specific about the pieces that they wanted. I talked it over with Alberto and we said, “Let’s do it. It will be really fun. It will kind of take the pressure off of us a little bit too, to have other people involved in this record.” So I did and we worked on it via MP3 files or by Yousendit/Dropbox stuff and when they sent me the mixes, I thought, “Oh, that’s great” and then I wasn’t even considering putting it on the album. I thought that something else would happen to it and that it wouldn’t be part of my album.

And then Alberto and I, every night when we finished recording, we’d have a drink and we’d put these tracks on that these boys did and we’d dance around the studio. We were up on our feet in joy. When I came to compiling the album, I thought, “I can’t leave this stuff out” and when I told them I was going to include it, they said “well, funny you should say that, because we sent it to this other mixer,” a guy called Raul Rincon, who is down in Ibiza, who does this clubbing stuff. He took the tracks that I’d done and did his version as well. He was kind of turned on by it and I thought, “I’ve got to include it. I can’t just ignore it and let it lie there.” So I hope it doesn’t disillusion or offend anybody, but it sure is fun.

It’s interesting to see where recording technology is now in comparison to ‘Days of Future Passed’ and ‘In Search of the Lost Chord’ so many years ago, where the recording technology was evolving day by day.

Yes, exactly. And it’s evolved even since I’ve been making this record, it’s moved on. It moves on almost weekly with some new piece of software or something that makes things different. And you have to know where to resist that kind of stuff and where to not tune everything that you do or not put everything completely in tick-tock time.

I come back to when I decided to put all of these tracks together, was when I was doing the Moodies 5.1 surround mixes. Thankfully, Universal came to the group and then the group knew, “Oh, Justin will do it.”

What I had was the quad tapes that Tony Clarke and Derek Varnels had done in the early days in the same studio with the same echo chambers that were on the original recordings with the same desk. I was just so astounded at the quality of it. It was just superb. I sometimes wonder how far we really have come?

You know, it’s difficult. And now, when you get software coming out that’s just trying to make you sound analog again. You end up mastering it with an analog feel and it’s all very odd. But it’s still a joy. It was a joy then when we were making ‘Days of Future Passed,’ even though it was only four-track. And it’s a joy now when it’s 176 tracks.

Listening to those quad mixes, was there anything that really was astounding to you, in the sense that you pulled it off?

That’s the overriding feeling for me, was how the hell did we do that? That’s the thing that astounded me. We were on a fast train in the ‘60s with our heads down, plowing away at this stuff, never really doing that much on the road. Never smiling in photographs and never really doing any press -- just going back in the studio and back in the studio and moving forward.

I realize now and I’ve realized since, when I’ve been responsible for remastering the Moodies stuff, how lucky we were to be in that place with a great engineer, to have the stuff recorded beautifully in beautiful stereo.

Unlike the boys who were down the road, the Beatles, at Abbey Road, who only ever really seemed to love mono. And I did too -- I never had a stereo system when we did ‘Days of Future Passed’ or ‘In Search of the Lost Chord.’

I never got a stereo system until about 1969. It was only when I went to America in ‘68 and listened to FM radio, I really thought “wow, there’s something in this.” But we were lucky to have those superb engineers that when it came to the digital domain, our stuff was just perfect for that. We didn’t have drums on the right and vocals on the left or something -- those stupid old ‘60s stereo things that they used to do.

When you look back at ‘Days of Future Passed,’ it doesn’t seem like from my view, that the band was in the best shape when you and John first joined. So it seems like it would be a difficult situation to walk into. You were recording the first proper album with the band and ultimately, you guys were working on an album that wasn’t even the album that the label had in mind.

No, that’s right. They wanted a demonstration stereo record and they wanted Dvorak -- they wanted a rock version of Dvorak. It was Peter Knight who made that decision to use our songs and I’m very glad that he did. He gave us the greatest break any group could possibly have.

Looking at the renewed success that you had in the ‘80s, you couldn’t have had a better pairing than the storyline connection between ‘Your Wildest Dreams’ and ‘I Know You’re Out There Somewhere.’ Was that connection there when you wrote the first song, or did that idea to link those two songs come later?

The success of ‘Your Wildest Dreams,’ which really, I thought it was almost a throwaway song. Tony Visconti was a big part of that [success with] his sound and his style. It was only when it came out that I realized that emotionally, it was a common experience for a lot of people. It occurred to me that I had other things at home that had that exact same feel and continued that sentiment. So I dove back into my home tapes and then I realized that ‘I Know You’re Out There Somewhere’ was there too.

So I was very conscious of continuing that feeling, because a lot of other people identified with it. And also because ‘Your Wildest Dreams’ had given us the greatest gift -- to have a hit and be recognized on MTV and stuff when you’re hitting 40 was marvelous. And straight -- I wasn’t even stoned in the ‘80s that much.....I missed it in the ‘60s!

‘The Other Side of Life’ was a really interesting track to hear from The Moody Blues in that era.

Yeah, it was. And it came about because of where Tony’s studio was, right in the middle of Soho in London and what we would do after we finished recording and [what was happening in] the clubs up and down Water Street. It’s a part of London and a part of the world that I hadn’t seen since I was 16 or 17 years old when I first came to London. So I wanted to express that in the song and it was a very odd kind of place and an odd sort of atmosphere, where Tony had his little haven of peace and serenity in the middle of this madness in the middle of London. That definitely came through in the song.

More From Ultimate Classic Rock