The Night the Beatles Played Their First Hamburg Show

The stints the Beatles did in Hamburg, Germany, are widely credited with turning them from just another teenage band in Liverpool into a tight rock 'n’ roll combo. They played their first night on Aug. 17, 1960, at the Indra Club.

They had gotten their gig through Allan Williams, who owned the Jacaranda Club in Liverpool and managed a handful of local groups, including the Beatles. He had developed a working relationship with Bruno Koschmider to send his acts to perform residencies at the Indra and the Kaiserkeller, both owned by Koschmider.

They hired Pete Best as the band's drummer a few days before. For the previous two months, Paul McCartney had moved from guitar to drums, but Koschmider specified that he wanted a five-piece band, so bringing on Best, whom they knew from the Casbah Club – owned by Best’s mother – was a natural choice.

They arrived in Hamburg and, after stopping at Koschmider’s house where they were to stay the first night, went to the Indra on Grosse Freiheit just off the Reeperbahn, the famous red light district in Hamburg’s St. Pauli quarter. The next night, and for the rest of their first Hamburg trip, their lodgings were in the Bambi Kino, a nearby theater, where they slept on bunk beds in the storeroom next to the ladies room.

Beatles Bible says that, for £2.50 a day per person, they played four sets between 8PM and 2AM on weeknights, five sets from 7PM to 3AM on Saturdays and six sets from 5PM to 1:30AM on Sundays. Their shows were comprised virtually entirely of covers of their favorite rock and R&B tunes, with stabs at whatever requests would be shouted at them by the drunken crowd. The long hours were a change-of-pace from what they were used to, but it forced them to adapt, especially with Koschmider repeatedly urging them to mach shau — to “make a show.”

“In Liverpool, we just used to do our best numbers, the same ones at every gig,” John Lennon said in Anthology. “In Hamburg, we would play for eight hours, so we really had to find new ways of playing. … We got better and got more confidence, playing all night long. It was handy, them being foreign. We had to try even harder, put our heart and soul into it, to get ourselves over.”

They dealt with the exhausting shifts thanks to the introduction of Preludin, a stimulant used as an appetite suppressant, into their diet. “[T]he waiters, when they’d see see the musicians falling over with tiredness or with drink,” Lennon continued, “they’d give you the pill. You’d take the pill, you’d be talking, you’d sober up, you could work almost endlessly — until the pill wore off, then you’d gave to have another.”

“We were frothing at the mouth,” George Harrison added.

Another way they passed the time was by indulging themselves in some of the other activities that draw men to the Reeperbahn. “It was a sex shock,” Paul McCartney later recalled. “[S]uddenly, you’d have a girlfriend who was a stripper. If you had hardly ever had sex in your life before, this was fairly formidable. Here was somebody who obviously knew something about it, and you didn’t. So, we got a fairly swift baptism of fire into the sex scene. … We all got our education in Hamburg. It was quite something.”

The Beatles played the Indra until early October, when it was closed due to regular complaints about the noise. But Koschmider moved them into the Kaiserkellar, where they split time with another Liverpool band, Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, whose drummer was Ringo Starr. It was during this period that they met two people who would play a major part in their history.

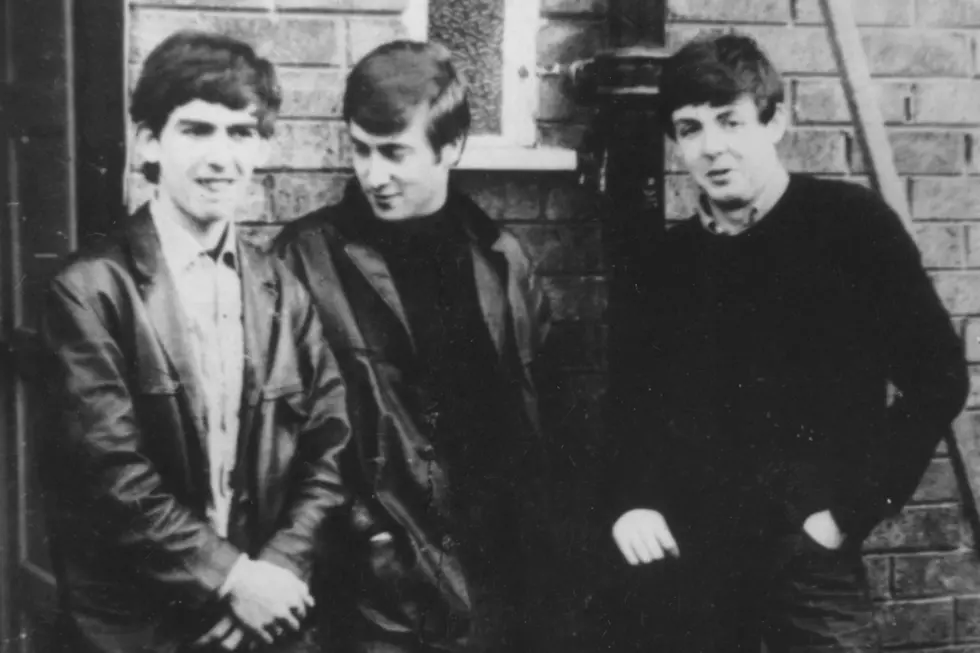

Klaus Voormann, a young German artist, walked into the Kaiserkellar one night during the Beatles’ set. Struck by what he heard, he invited his girlfriend, a photographer named Astrid Kirchherr, to see them perform. They became regulars and befriended the band, in particular bassist Stu Sutcliffe, who was also an artist. Kirchherr took some photographs that became the definitive portrayal of their Hamburg era, and she and Sutcliffe soon fell in love.

Sutcliffe also took a liking to Voormann’s hairstyle, which was common among the German art scene, and asked Kirchherr to cut his hair that way. Lennon, McCartney and Harrison soon followed — it didn’t work with Best’s naturally curly hair — and, a few years later, it would be synonymous with the Beatles’ image. Voormann would go on to design the cover of Revolver and play bass on solo sessions by Lennon, Harrison and Starr as well as Harry Nilsson, Lou Reed and Carly Simon.

By the end of October, the Beatles’ reputation had grown and they attracted the attention of Peter Erickson, who owned the Top Ten Club. He offered them more money and better living conditions and the Beatles jumped at the opportunity. Koschmider retaliated by notifying the German authorities that Harrison was only 17 and therefore ineligible to work, which led to his deportation a few weeks later.

They continued in Hamburg as a quartet, but not for long. Upon retrieving their belongings from the Bambi Koni, McCartney and Best nailed a condom to the wall and set fire to it. Koschmider had them arrested for trying to burn the theater down. They spent the night in jail and were deported the next day. Lennon joined them back in Liverpool a few days later.

The Beatles returned to Hamburg in March 1961, a month after Harrison turned 18, staying for three months and backing up Tony Sheridan – another Brit who was having success in Hamburg – for a recording session. However, when this residency ended, Sutcliffe decided to stay in Germany with Kirchherr.

On April 10, 1962, three days before the Beatles’ final stint in Hamburg, Sutcliffe died of a brain hemorrhage.

A park at the intersection of the Reeperbahn and Grosse Freiheit was created in 2008 and named Beatles-Platz. Situated atop black pavement designed to look like a vinyl record stands five statues representing the Beatles as a reminder of the importance of the city in the group’s development.

Rejected Original Titles of 30 Classic Albums

Why the Beatles Hated One of Their Own Albums

More From Ultimate Classic Rock