How the Who Struggled With Getting Old on ‘The Who by Numbers’

After releasing two of the greatest rock-concept albums of all time in Tommy and Quadrophenia, the Who had nowhere to go but down — at least in terms of overweening ambition, anyway. The result, 1975's The Who by Numbers, proved a critical and commercial triumph in the face of personal adversity.

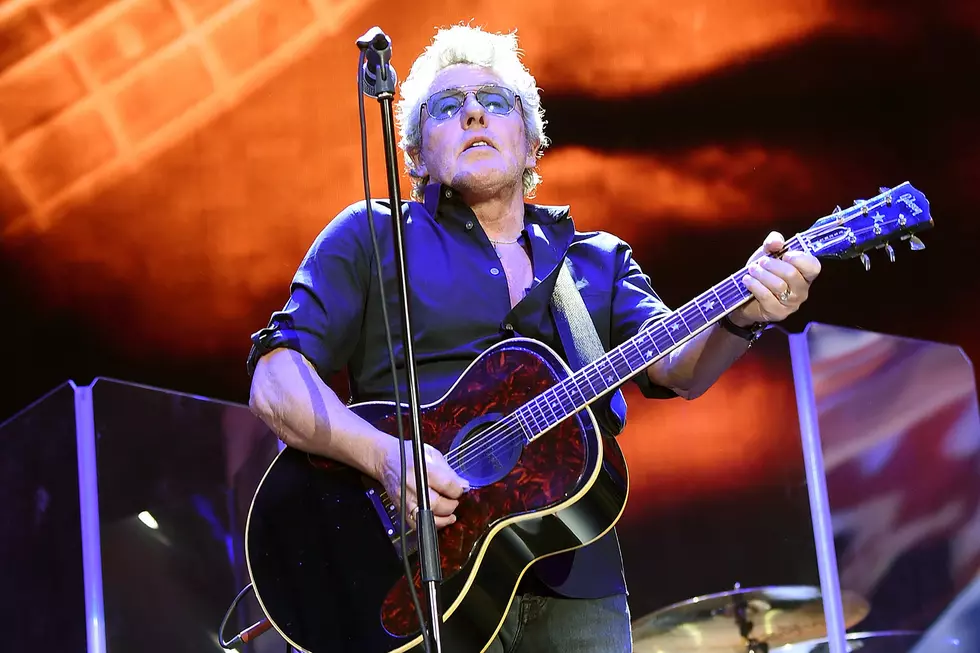

At the time, the band were battling demons on two fronts. On one hand, they felt somewhat boxed in after setting the template for rock concept records. As singer Roger Daltrey complained, fans and critics expected the band's albums to come with a certain amount of heft, to the point that they sometimes weren't willing to give non-concept efforts their proper due.

Grumbling that "nobody wanted to listen to what [else] we were doing" after Tommy came out, Daltrey argued to Rolling Stone, "Who's Next holds up much better, but nobody wanted to take it seriously because it was just nine songs and no great thing about a bloody spastic."

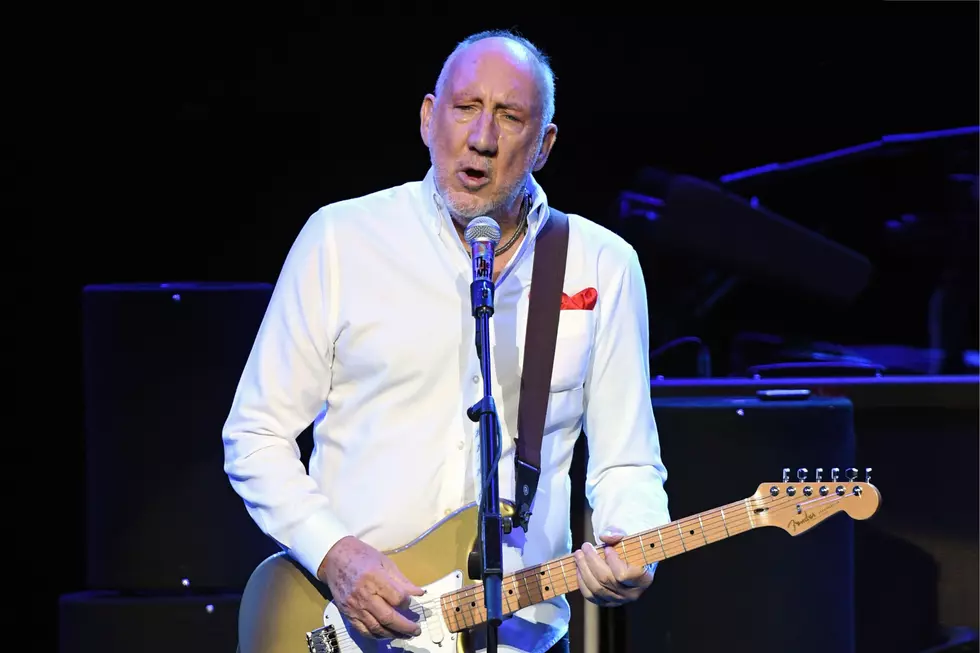

Further complicating things was the band members' increasingly critical view of where the Who stood — or should stand — in a turbulent musical landscape that had grown to encompass styles that seemed to exist in contrast to the growing complexity and maturity of the band's own work. For guitarist Pete Townshend, who wrote the bulk of the material, the question proved particularly vexing.

"Before the emergence of punk, the Who were the only band who actually sat round a table to decide 'Should we go on or not?' Would we be doing music a favor if we just fucking stopped? We actually considered that," Townshend told NME "Around the time of The Who by Numbers, we used to have really quite heavy conversations about where music was going to go – particularly in this country – and whether we should be involved in it, and the problem with [drummer Keith Moon] living in America and living that Hollywood lifestyle and whether we should try and force him to come back to England ... all those kind of things," he continued. "Whether our music should change, whether we should let the Who tradition just bash on until it got really boring, whether we should try and force change by starting labels and working with other bands."

As Who fans are well aware, the band opted to forge ahead with their seventh studio album, The Who by Numbers, which arrived in stores on Oct. 3, 1975 — nearly two years after Quadrophenia, and a relative eternity during the speedier release cycle that was the norm at the time. Realizing their rather chaotic state would make recording more of a slog than normal, they enlisted producer Glyn Johns to help wrangle the sessions into shape, and as the weeks dragged into months, Johns earned every penny of his paycheck even though the album's aesthetics were less intricate and synthesizer-driven than the recordings that had preceded it.

"Glyn worked harder on The Who by Numbers than I've ever seen him. He had to, not because the tracks were weak or the music poor but because the group was so useless," Townshend said in Alan G. Parker and Steve Grantley's The Who by Numbers. "We played cricket between takes or went to the pub. I personally had never done that before. I felt detached from my own songs, from the whole record. Recording the album seemed to take me nowhere. Roger was angry with the world at the time. Keith seemed as impetuous as ever, on the wagon one minute, off the next. [Bassist John Entwistle] was obviously gathering strength throughout the whole period; the great thing about it was he seemed to know we were going to need him more than ever before in the coming year."

Listen to 'However Much I Booze'

The result was a collection of moody, introspective and dark songs; though tracks like the opening "Slip Kid" and hit single "Squeeze Box" went down easy enough, The Who by Numbers is more strongly defined by self-critical Townshend compositions like "However Much I Booze" and "Dreaming from the Waist"; even the lighter-sounding "Blue, Red and Grey," which found Townshend strumming a ukulele on top of a brass section overdubbed by Entwistle, was later described by Townshend in a Numbers reissue's liner notes as "me wanting to kill myself."

Between the subject matter and the rumors of band strife that pervaded the music press at the time, the popular opinion was that The Who by Numbers offered a sort of grim personal manifesto from Townshend as he approached middle age — and although he's more or less confirmed that point of view a number of times over the years, he's also cautioned that listeners shouldn't try to read too much into the songs, insisting what he was really trying to do was put himself in his audience's shoes.

"There are a couple of really politically incorrect lines on Quadrophenia, but I thought I could get away with it because I was writing for a character. But on By Numbers, everybody took everything really literally. I don't know. It's interesting," Townshend told Rolling Stone. "I certainly didn't feel a lack of friendship and I certainly didn't feel suicidal. I think I may have been a bit angry occasionally. I think I need to go to the great journalistic psychiatrist and have it explained to me, why I was wrong and they were right."

Perhaps more importantly, according to Townshend, Daltrey was actually more responsible for the overall theme of the album. "The songs are about being older, feeling lost, losing your way," Townshend told Mark Blake. "Changing fashions, being sentimental, looking at the sunrise. What's that got to do with being a young man? You don't start looking at the sunrise until you're dying. But," he added, "Roger picked those songs from my demos."

As Townshend noted, the album was filled with songs in which one artist interpreted the words of another — which were themselves interpretations of Townshend's efforts to put music to what his audience was going through. "Roger's an actor," he argued. "I don't think he realized that what he was doing all the time with my work was interpreting, acting — and I couldn't do that. I couldn't be an actor and he could."

Daltrey, for his part, still believes the album is more autobiographical than Townshend would perhaps like to admit. "Who by Numbers is very dark because Pete was going through some terrible agonies, but I didn’t realize this at the time," he told Uncut. "We thought, if he wants space, we’ll give him some space – when what we should have done was been there saying, ‘You all right, Pete?’ But that’s just the way he was and still is. There’s a side to him that is like a stone wall and what he really wants you to do is knock down the fucking wall and come through it, which takes a lot of effort all the time. I understand it now but I didn’t understand it then. So it led to this brooding, deep, introspective album. He was boozing a lot and I think he was having problems with his marriage, trying to balance that family life with rock ’n’ roll, 'cause they don’t balance. But I love that album."

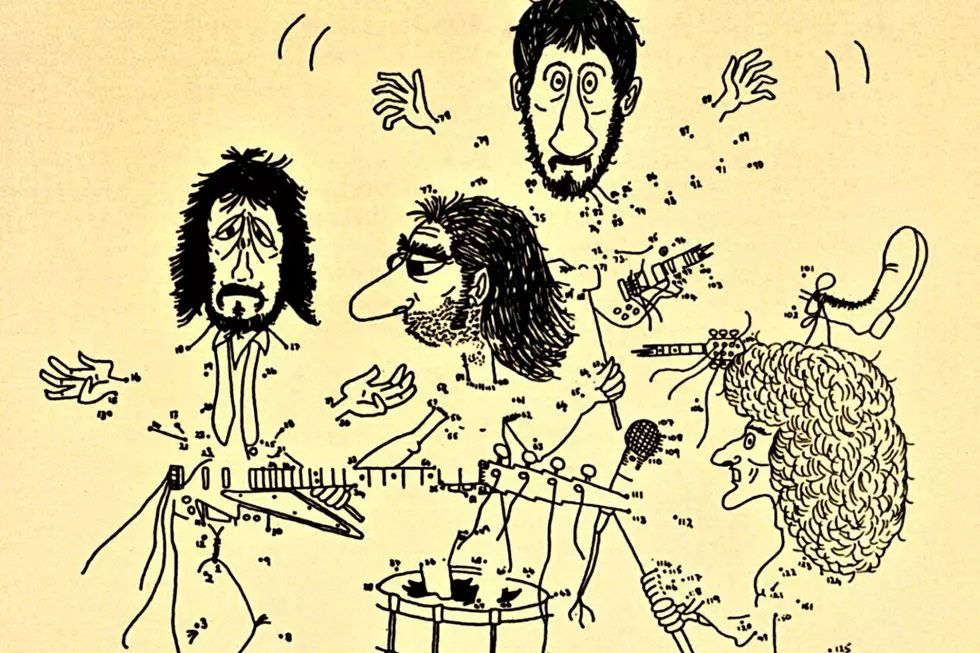

However you take the songs, The Who by Numbers proved yet another hit for the Who, with "Squeeze Box" entering heavy rotation on both sides of the Atlantic while the album hit the Top 10 in the U.S. and U.K. on its way to RIAA certification for half a million in sales. And while Townshend may have sweated the songwriting during this period, other members of the band seemed perfectly content — including Entwistle, whose hand-drawn album art reflected the record's scaled-down sensibilities.

"The best we've done since the last one," chuckled Entwistle when asked for his thoughts on The Who by Numbers in a 1976 interview with Sounds. "I like the cover. That's pretty good."

The Who Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock