Revisiting Paul McCartney’s ‘Chaos and Creation in the Backyard’

With Chaos and Creation in the Backyard, Paul McCartney created a kind of McCartney III, but avoided the missteps of his two earlier self-titled solo projects.

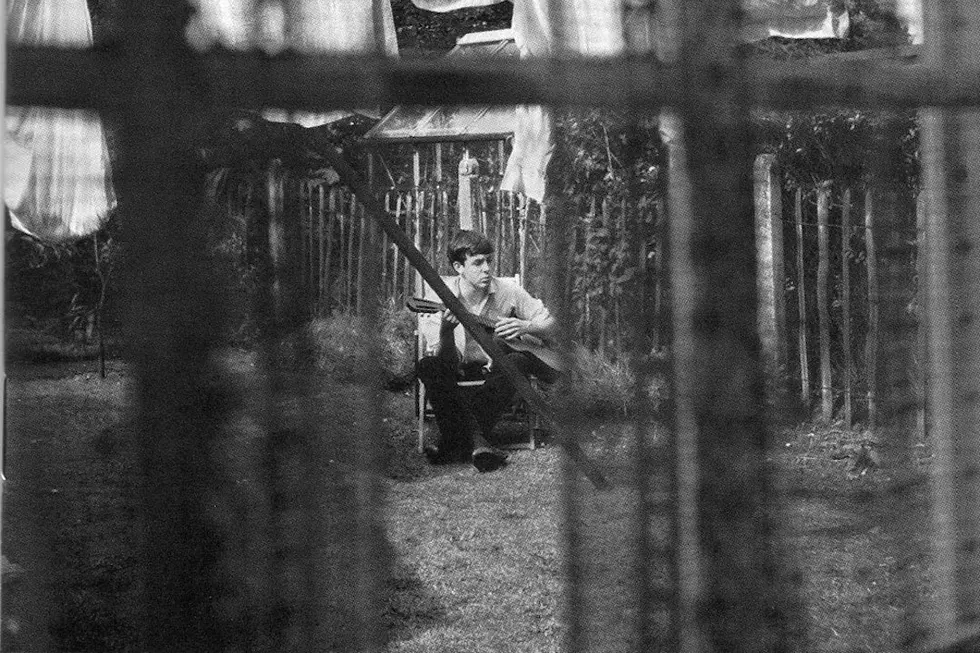

In both cases before, McCartney had constructed an album entirely on his own after the demise of famous groups, first the Beatles and then Wings. But his efforts at establishing himself as a separate entity led to a couple of pitfalls, first with the incomplete-sounding McCartney in 1970 and then the overly mechanized preoccupations of McCartney II. You could argue that his intentions – that is, in the first place, to strip back the pretensions of his work with the Beatles and, in the second, to challenge himself with new musical sounds – were good. Unfortunately, some sense of purpose was lost in the echo chamber of working alone.

Chaos and Creation in the Backyard, which was released on Sept. 12, 2005, brought another voice into the conversation with producer Nigel Godrich. Most famous to that point for his work with Radiohead and Beck, Godrich nudged McCartney away from his worst tendencies – creating a modern-era classic that succeeds where McCartney and McCartney II stumbled.

McCartney again handles most, if not all, of the instrumentation, but Godrich refused to leave well enough alone – leading to no small amount of needed tension. "There were one or two moments on the album when I had to think to myself, 'You know, I could just fire this guy,"' McCartney told the Associated Press.

To some degree, this initial chafing is to be understood. McCartney had, to this point, produced every one of his own projects dating back to 1984's Give My Regards to Broadstreet. Eventually, he came to appreciate what Godrich brought to Chaos and Creation in the Backyard. Together, they created a solo effort that refused to settle into either the comfy, half-drawn sketches found on McCartney or the half-baked stabs at modernity that sunk McCartney II.

"He wanted to keep it really simple, really straight, really direct and very me," McCartney added, "instead of 'Let's get modern; let's get gimmicky' or 'Let's do this because it's the latest groove.'"

Along the way, they'd clash over songs – McCartney wanted to speed up "Riding to Vanity Fair," for instance, and Godrich wanted precisely the opposite – and they'd clash over instrumentation. Initially, McCartney was content to use his regular touring band, a group that has now been together longer than either the Beatles or Wings. Godrich, who felt that worked inside McCartney's comfort zone, flatly refused.

“Nigel had his own agenda,” guitarist Rusty Anderson said back then. “He had it in his mind that McCartney and the band were very close, which we are, and he wanted to break it up because he felt that he couldn’t challenge Paul one-on-one if he were supported by the band. I think it was a dopey move, but I do understand.”

McCartney assumed a more central role in every element of the project. He's credited, for instance, with guitars, piano, harpsichord, flugelhorn, melodica, drums, shakers and tambourine on "Friends to Go." At the same time, however, Nigel Godrich helped focus McCartney's more experimental side. "Jenny Wren," a spare acoustic cousin to "Blackbird," is enlivened by a guest solo on duduk, a haunting Armenian woodwind. He added strings, but none with arrangements that recall earlier work with George Martin, who originally recommended Godrich to McCartney.

If there's a criticism to be levied, it's that Chaos and Creation in the Backyard became McCartney's most downbeat album. The should've-been-a-hit opener "Fine Line" and a searing solo on "Promise to You Girl" represent the only overt nods to rock. But it's also one of his most honest works.

"Even though I'm essentially an optimist, an enthusiast, like anyone else I have down moments in my life," McCartney told the Associated Press. "You just can't help it. Life throws them at you. In the past I may have written tongue-in-cheek, like 'Maxwell's Silver Hammer,' and dealt with matters of fate in a kind of comical, parody manner. It just so happens in this batch of songs I would look at these subjects and thought it was good for writing."

The result is something entirely different, both in form and content, from the typical McCartney recording. Love-struck lushness is replaced with delicately surreal atmospherics, love-struck lyrics with brave examinations. Forced out of artifices that girded the tossed-off McCartney and the synth-crazy McCartney II, McCartney finally found his solo voice here.

Paul McCartney Albums Ranked

More From Ultimate Classic Rock