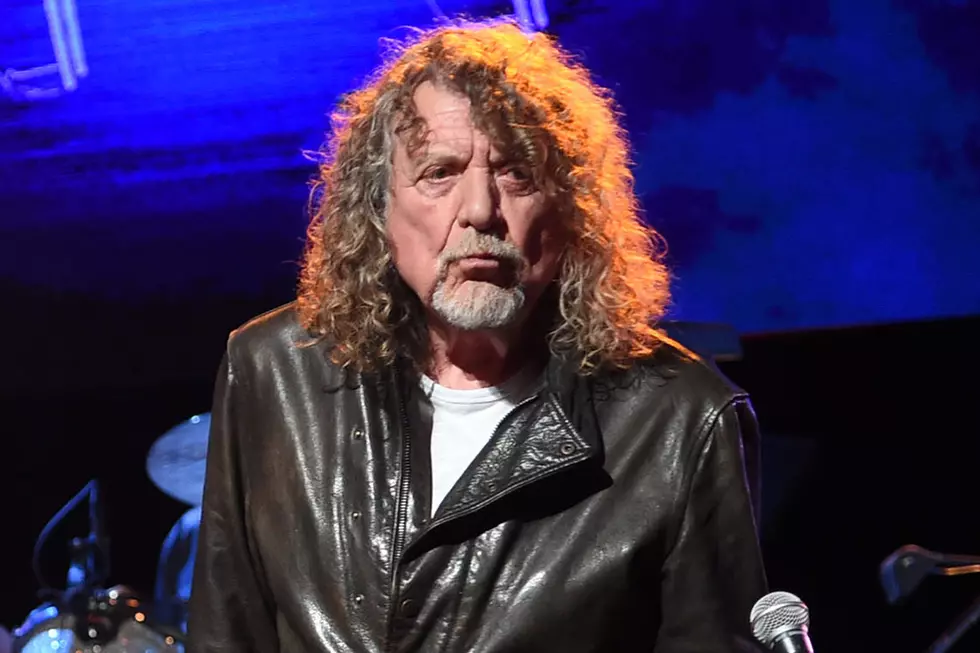

Jimmy Page Talks Led Zeppelin Reissues and Legacy, With an Eye on the Future: Exclusive Interview

Jimmy Page has a lot of ideas about what he’d like to do next, now that the final three Led Zeppelin reissues have been released. Page recently discussed those plans, and talked more about his return to Presence, In Through the Out Door and Coda, with Paul Shaffer.

Shaffer, of course, just wrapped up more than three decades as the bandleader and sidekick for The Late Show with David Letterman. He continues to host Paul Shaffer’s Day in Rock, a syndicated daily rock history radio feature – and there was, of course, plenty of history to discuss with Jimmy Page.

In Through the Out Door is one of three Led Zeppelin deluxe edition reissues that are on sale right now. What does a fan get if they buy one of these right now?

The deluxe reissues of all of the catalog albums, but certainly the ones that are being released right now, each edition has the original studio album as everyone knows it – but there’s also another supplementary disc, a companion to the original audio, which has various versions of songs, songs that have never appeared before, stripped-down versions. Across the whole of the catalog, you know, that’s a substantial amount.

The original album, as everybody knows it, now when you say that, has it been remastered or remixed? Any tweaks?

I remastered it basically across every sort of sonic aspect that you could sort of listen to music on, as far as I could maintain. So, in other words, that’s equipped for digital and it’s been remastered also for CDs even, and the vinyl. I really wanted to make sure that the detail could be heard in all of these things – unlike, say, MP3 files. It really opens it all up. You can hear it all properly. And then as I say, with each studio release, there’s a companion disc with all of this extra material. It doubles up the amount of studio material that was out there originally in the Led Zeppelin catalog. There’s now literally twice as much.

With Presence, I understand it was recorded relatively quickly, somebody said in just 18 days. Is that so?

Well let’s say that it is, it’s 18 if it’s not 19, but literally, yes.

It’s pretty quick by the standards of the day when people were laboring over these things for months.

We worked really fast. We always worked fast with a sort of ruthless efficiency, I would say. The first album was done in a very short time and by that, I mean collectively 30 hours, 36 hours maximum. So that was always something to remind ourselves of, but we never took a long time doing albums, that’s for sure. But at that point of time, to have a two-and-a-half or three week slot to go in and record was the idea of it.

You would go in prepared, with stuff already written.

We’d have the backbone of the songs, you know, what we’d call the running order of it, what’s going to be the track. I’d say somewhere maybe 60 percent of the album was rehearsed in Los Angeles and then we get to Munich to do the recordings, numbers sort of come out of thin air there, like “For Your Life” and “Tea For One,” were things that actually came out in that short space of time in the studio.

What were you doing in Munich?

The studio had a really good reputation. I liked things that I had heard that had come out of there and it also had a really good reputation for reliability. You know, in these old analog days, sometimes things might break down. They had a really good track record.

You brought your own engineer, of course.

I did, I did. His name was Keith Harwood and he was an engineer that I had a real connection with. He did all of the mixes on the Physical Graffiti album and he was the engineer when we put the orchestra on “Kashmir.” You know, we had a bit of a history.

When you listen to these things now, what do you think about when you hear, for instance, Presence?

When I listen to that, it was the one area during the process of listening to all of these analog tapes. It was hundreds of hours, because you’ve got to listen to it in real time.

Nobody else did this but you.

I couldn’t do it. It’s not the sort of thing where you can pass it off to somebody else, like an assistant, and say, “Well, tell me what’s good out of this.” No, I had to go through and make all of the notes, copious notes and annotations. You can imagine. But the Presence tape turned up and it was really crucial that this tape turned up when I was searching through, because otherwise it would have been the hole in the middle of these releases and we couldn’t afford to have it. Presence turned up and it showed even numbers that had been sort of forgotten about. There’s a number called “Pod,” which is a keyboard number, so you’d like that.

Of course I would like that! I want to ask a question about guitars. Somebody said that Keith Richards right around that time said that you should have a second guitarist in the band.

Yeah, he did, that’s right. Because they had had second guitarists in the band. Even from the very early days of playing electric guitar when I was a kid, I was always in bands that it was just bass, drums and guitar, until I got into the Yardbirds. And then the Yardbirds trimmed back down to bass, drums, guitar and singer. So I was really sort of used to that and sort of filling the guitar parts in.

And no keyboards, normally.

Not in those days. But then of course, with Zeppelin, we did have keyboards, but you know, there was only the four of us playing at any one point on stage for example. But when I put together all of the guitar overdubs for “Achilles Last Stand,” which was a long complicated arrangement, a lot to remember.

It was like, over 10 minutes long.

Yeah, it’s a lot to remember. I just laid these guitars down in the space of one night. So it was like all of the orchestration was in my head and I just sort of did it. Now, if he ever heard that, he’d probably say they need a second guitarist, and maybe a third and a fourth and a fifth and a six, to be able to do that.

In Through the Out Door was the final album of all-new material that you guys released. Had the band stayed together after that, what kind of musical direction do you think they would have gone in?

Well, In Through the Out Door, the rehearsals of that, John Paul Jones comes in with a Yamaha Dream Machine keyboard, which is a keyboard that Stevie Wonder had. You know that one?

It was a big mother.

Huge, great thing! So, suddenly there’s this great thing that he’s brought into the studio and he’s sitting down with it and he’s been rehearsing with it at home, practicing. Not only has he been practicing, he’s actually written some songs – which up to that point in Led Zeppelin, he hadn’t done that.

He’d never written ...

Well, he might have come up with a bit here and a bit there, but he didn’t have a whole concept of a song – and he had a few. So, it made perfect sense to do a keyboard album after a guitar-driven album, kind of an “I’m coming at your jugular” sort of album like Presence, and it was a good thing to do. The question of what would we have done afterwards, in between the time of the recordings of Presence and In Through the Out Door, there was a track called “Bonzo’s Montreux,” which was like a drum orchestra – it was a drum orchestra. You can hear how John Bonham really liked to play the drums and you can tell through the whole of the catalog. He and I had spoken about what we’d do after, on the tour we were doing in 1980, we were talking about what we’d do as the next album, what sort of material, and it was the riffs. You know, he loved all of those riffs and getting into them and grooving and that sort of passionate playing that he had. So, I think that’s the way it would have gone for sure.

More of a groove-oriented thing.

Yeah, and tricky, sort of snakey riffs – the things that everyone knew us for.

And you did, when you went to the Indian cats and had that large orchestra, you were talking about a different groove, but it was certainly groove-oriented stuff.

The Indian guys, that’s literally going in with musicians who have never heard Led Zeppelin, classically trained musicians that did Indian film music. That was the pop music of the day in India. [We were] going in requesting a certain amount of the musical ensemble of the instruments and going in there with the acoustic guitar, no local arranger, and seeing whether it was possible to actually translate across what it was you were intending to do and get them to do this, that and the other – and I must say, it was a really successful experiment.

Let’s get into Coda. It was your final studio album as Led Zeppelin and it was a collection of unused tracks from the band’s 12-year career. When you first put this out, was there a lot of material?

We didn’t have John Bonham, but we did have this piece, “Bonzo’s Montreux,” which is like an orchestra. So under the circumstances, apparently we had an album to deliver, but we don’t have a band. Putting the producer’s hat on, I said, “Well, what do we have?” Well, we’ve got “Bonzo’s Montreux,” this drum orchestra. And this is the time to feature it. I was working from the multi-tracks on all of the material that is on the original Coda in 1982. There were tracks that were left over from the In Through the Out Door album, so it was sort of pieced together. However, when it comes to doing it now, I’d already worked this out, right at the beginning stages of how you start a project like this and how you end it – and I wanted to end it with a double disc to compliment the original album, so it became the mother of all Codas, and a real celebration of Led Zeppelin’s music and a real potpourri of it.

"Coda," technically define it as a musical term, for the audience.

Well, it’s the last part, isn’t it?

The final movement.

You get the final movement, you go to the coda and then it will stop, if you’re lucky. Because it could just keep repeating forever.

But it will probably stop.

No, it does. It’s a final sort of chord. The last chord.

35 years later, listening to these great songs, what if you had today’s technology? What would you do differently if you were cutting these things today?

Well, my approach to it would still be to capture the performance of an artist, to capture that. That’s what all of this stuff is – the Led Zeppelin music and the music of the ‘60s and ‘70s of other artists – it’s capturing the essence of why you’re doing that particular track, the character of that track and the collective performance of the musicians and of their overdubs, etc. In those days, if you were doing vocal overdubs, you’d go for it and you might maybe make it up with a couple of drop-ins, but that’s it, you go for the full performance, not compiling it syllable by syllable or word by word. So, what it is is that you had to be direct, you had to make your mind up and be positive and deliver. You didn’t have the option of having maybe 50 different options of what you could do and take it easy. Don’t take for a moment what I’m saying is that I don’t really appreciate all of the stuff that goes on with computer mixing, because I think it’s brilliant what goes on. But as far as performance, it’s a different thing altogether, isn’t it, Paul?

God bless you for trying to maintain it. Have you got anything in mind to do next?

Well, yeah, yeah, because I’ve been over the last number of years, concentrating on Led Zeppelin product. I really felt passionately that all of this studio information should come out and should be there. It’s finished.

What’s next?

Playing the guitar, that’s what it is. I’ll have the time now to be able to put that passion and energy and focus into playing the guitar.

How are you going to do it?

Well, I’m going to work on the guitar or guitars plural, because I’m known to play in so many different styles and that’s what I am, so I just want to get there and just basically reconnect with all of these things and see what happens. Now that all of the Zeppelin stuff has come out, I have the freedom to be able to make new music, manifest new music and be seen to be playing, as opposed to just rumored to be playing.

You were a studio musician, as I was, playing dates as we used to say in New York, just playing sessions. I know you played for everybody during the British Invasion.

For about three and a half years, I was a studio musician.

You were a studio player for three and a half years. Herman’s Hermits, did you ever play on a session for them?

You know, I didn’t play on Herman’s Hermits, no.

John Paul Jones did some charts for them, I know that.

John Paul Jones did Herman’s Hermits. But I did play on Donovan’s “Sunshine Superman,” do you know that?

[Shaffer starts humming the riff]

Yeah, that’s it!

I know it note for note, are you kidding? You created a hook! I’ve always wanted to ask you this, because this is rock and roll history and people get confused. “You Really Got Me.” Did you play on that?

No, it got sort of distorted. I did play on some Kinks records, but I wasn’t on that one – but I never said I was.

Funny how these things start ...

But I was on, for example,“I Can’t Explain” by the Who. I’m not needed and you can just sort of barely hear the riff guitar going on behind it. It’s Pete [Townshend] doing all of the 12-string stuff. I got contracted in to do it, so on the B-side you can hear a few phrases on the sort of fuzztone thing that I had. But what a session to be able to say that you were at! The energy of it was phenomenal, Paul. It was great. Pete’s playing like a hooligan, isn’t he?

Yeah, kind of Kinks-esque.

Yes, it is, yeah.

You can almost attribute it as an homage to them. How do you go from being a studio player doing sessions where anybody’s liable to come in, and all of the sudden you create the heaviest band in rock and roll? Does one thing come from the other? Were you developing your sound for Led Zeppelin early?

Talking about developing the sound, I was the first person – I pioneered what you know as a distortion box, the overdrive, the fuzzbox tone bender. Somebody came to me who worked at the Admiralty in their secret department of electronics and he said, “I want to do something in music. I want to make something for music. Have you got any ideas?” I said, “Come to my house, I’ll play you some records.” I played him stuff with really overdriven guitar and I said, “That’s what we want to [sound like].”

Like what? Because who was doing this before you? Are you talking about blues guys?

Yes, absolutely. They’ve got those old amps and they just really –

Turn them up with a lot of sustain.

Yeah, and the other thing was to be able to get notes to sustain for a long time and the overdrive. He came back with this pedal and you know, I duly bought it off him and he hadn’t made one for anybody else at this point. This is the pioneering one of it – I’m a studio musician, picture yourself in these shoes. I walk in and I’m a young kid – I’m seven years younger than anybody else – and I’ve got this thing and I said, “I’d like to use this on this” and suddenly, everybody goes, “Oh my God, what have you got there?” Because you know, you weren’t supposed to play really loud, but suddenly, I’ve got something which makes it sound like it’s [louder].

Even though it’s soft enough to work with the isolation in the studio.

Yeah, that’s it. So, at the time, I actually asked this guy to make one for Jeff Beck.

That was charitable of you. You gave it away, really.

Yeah, I mean, you had to travel this thing and the other main session guitarist, he said, “I want one of those,” you can imagine. [Laughs.]

What was the session? Do you remember?

I’m not sure what it was with that other guitarist – it might have been a P.J. Proby record, if you’ve ever heard of him.

Well yes, we know of him as a guy who split his pants. That’s the only thing we know.

Well, he was from America.

Yeah, but he was in England. He worked for Jack Good and he split his pants, but that’s neither here nor there. [Laughs]

That wasn’t because of the distortion box.

Well, maybe it was! Listen, Chris Squire of Yes passed away back in June and you had a band with him.

Well, we didn’t actually [have a band], but we played together. I had a studio and Chris and Alan White came to the studio and we did a getting together [jam]. It was the first thing that I did after losing Bonzo. I hadn’t been really that keen to play guitar. I put it down for a little while. They more or less said, “Why don’t you come and play with us?” I thought, “Boy, this is really just what I need.” It’s like they put the gauntlet down, like, “Okay, come on then, let’s see what you’ve got.” Because these guys are superb musicians. We had some great times in the studio. They had a name for a band – it didn’t get any further than the studio – which is XYZ, which is ex-Yes and ex-Zeppelin.

Did it come out?

No, it’s still sitting there in my archves. Maybe it would be nice to actually do something with it, because it’s really, really good music.

Would you ever release that stuff?

I would. You know what, to be truthful, I was waiting for all of this to finish and then contact Chris and Alan and, of course, now we’ve lost him.

Anything else in the archives that you might release?

No, not really. I really need to be doing something which is just totally fresh.

Favorite Led Zeppelin song?

They’re all favorites. They honestly are, because that’s how they were, they were all sort of crafted and they went on the albums because they were all favorites at the time and all very, very different. In the context of everything, I guess “Good Times, Bad Times,” first album, first track, side one, it’s going to change everything overnight. You know, it changes drumming, it changes recording processes ...

Did you know it at the time?

With Led Zeppelin I, with what it contained, yes I did.

When you cut “Good Times, Bad Times.”

Well, no, I just knew across the course of what there was on the album. I knew it really changed things. Whether it was going to catch on or not, [I wasn’t sure]. It might be too radical, because it was pretty avant garde in places.

It sure was.

It really was.

See Led Zeppelin and Other Rockers in the Top 100 Albums of the '70s

You Think You Know Led Zeppelin?

More From Ultimate Classic Rock