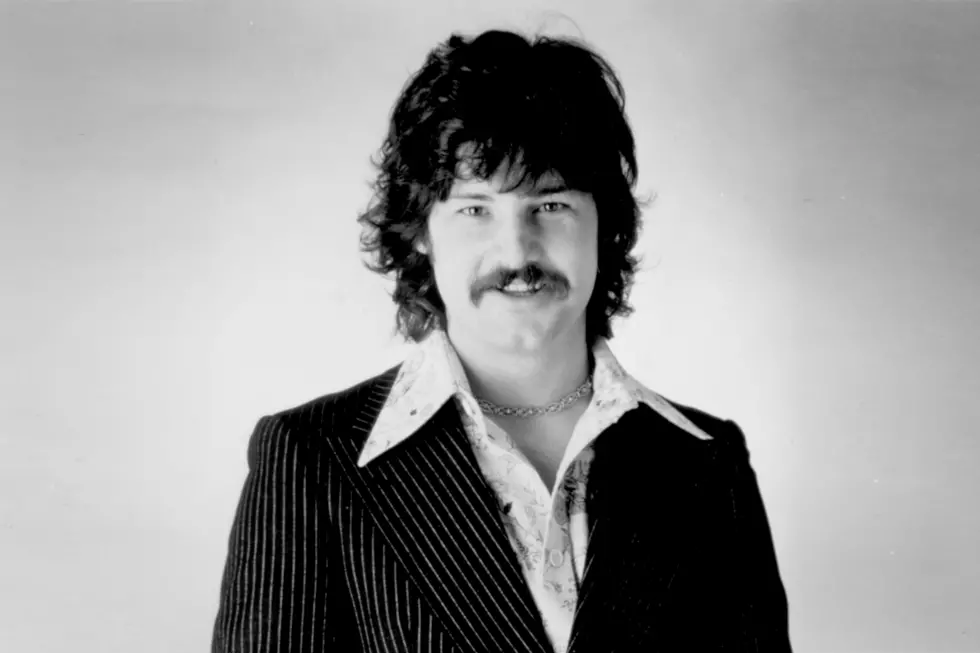

Randy Bachman on the Guess Who, BTO and His ‘Heavy’ New Album: Exclusive Interview

Even in his younger years, Randy Bachman was a driven individual – the guy who put the “overdrive” in Bachman-Turner Overdrive. During a conversation with Ultimate Classic Rock, he reflected on the long journey toward his new album Heavy Blues, one that began with Bachman's abrupt departure from the Guess Who.

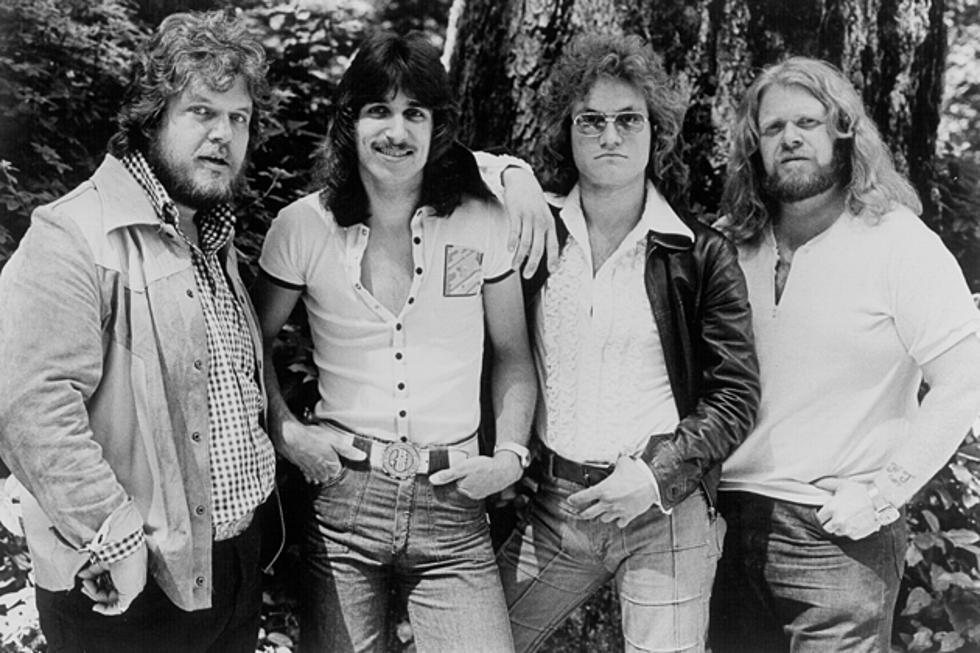

That was in 1970. Bachman immediately set about putting together his next project, the band that would become BTO. Despite the odds, he was confident. Having had success, Bachman knew how to claw his way back to the top. He just needed the right players, and that meant musicians who had their priorities straight. “I came out of the Guess Who – who were, like, turning into a bunch of kids in high school, innocent, learning to first of all, smoke cigarettes, then drink, then smoke joints and snort joints, then smoke hash and then snort white powder and stuff,” Bachman remembers. “I saw guys killing themselves, guys going into comas, taking LSD and never coming back out of it.”

Ultimately, Bachman made a life-changing decision. “That just frightened me to death, so I stayed away from it myself,” he says. “Whenever the bands I was with were getting into that, I just left the band, when it came too overpowering and I couldn’t control it anymore. When I started BTO, it was, ‘Okay you guys, I know where to go, I know how to go -- I know the bus. I got a ticket to the bus. Do you want to jump on? I’m going back to the top. It might take a month, a year, five years, 10 years. I’m going and I know where to go.”

There were conditions, however, for his prospective bandmates. “Here’s my rules. I do not want to waste my time on you if you’re going to be partying and getting chicks and getting drunk and being late. This is a business, okay? I’m risking all of my money and I’m giving you guys a salary and I’m producing and publishing the album. Nobody will work with me. I’ve left the No. 1 band in the world. American Woman was the No. 1 album and single and I left. I’ve got to do this on my own. There’s nobody helping me. If you can’t keep my rules, do not be a hinderance to me. I’ll get somebody else."

And so began Bachman-Turner Overdrive, but then a similar pattern emerged. "They all came on board,” he recalls. “The minute everybody was a millionaire and a superstar, they all started doing that stuff and it was time to leave. I can’t let anybody drag me down. It’s hard enough treading water in the world on your own, never mind getting a guy who is not kicking his feet or paddling along with you.”

More than four decades later, Bachman has started yet another band, yet still maintains a similar intensity. Heavy Blues is credited simply to "Bachman," the new power trio that he’s assembled, featuring drummer Dale Ann Brendon and bassist Anna Ruddick. The group worked quickly to lay down an album’s worth of material live in the studio, produced by Kevin Shirley (Aerosmith, Iron Maiden, Journey) with an aim to capture “the power of the late ‘60s,” in Bachman’s words.

“Before that, bands used to have two guitars, bass and drums – you know, the Ventures, the Shadows, the Beatles, the [Rolling] Stones," Bachman explains. "There was always an extra guitar. To suddenly be missing that guitar and the power of guitar, bass and drums that was Cream, [Jimi] Hendrix, [Led] Zeppelin and the Who, it gave each guy a little bit more space to fill in with licks and rolls and then you got more out of a three-piece than you did out of a four-piece as far as individuals playing, right? It sort of created something different. I kind of always wanted that, and just found it by accident.”

Bachman later talked about the way Heavy Blues came together, from finding a producer to collaborating with some of the project's signature guests, and how he plans to incorporate this new sound into an already-legendary repertoire.

What I love about power trios is that there’s no room for a weak link. Everybody has to be on their game.

Everybody is pushing all of the time. That’s the thing about this album. Burn a CD and put it in your car, go out on a nice day with the windows down and don’t get a speeding ticket – because the songs get more and more powerful and faster. You find yourself speeding and singing along and it’s like it’s 1969 again and you’re 18 years of age, driving along. You’ve got your driver’s license, and it’s a rock and roll summer, and suddenly there’s a red light flashing in your rear mirror and it’s the cops because you’re speeding.

This stuff provides a reminder of the time when material like this would just come ripping through your speakers --- or perhaps you were in a club or arena getting your hair blown back, hearing this stuff for the first time.

I think stuff now is so compressed and compartmentalized, because it’s in a computer. To be able to record like this with only a few microphones, live off the floor with nobody really knowing the songs and jamming the songs, with me yelling out directions over the mic. You can even hear it in some of the solos, I’m counting. You can kind of hear it there, because it’s leaking in all of the mics.

Sometimes I’d play a solo and sometimes I’d leave it out and then Kevin Shirley said, “Leave a lot of them out. I’ll get Joe Bonamassa to play on a track.” Once he got Joe on a track, I said, “Well, heck, I want to call Cristie Healey and see if I can use one of Jeff Healey’s tracks that he and I recorded live before he passed away. I want to fly his guitar in.” I got that done and I got Neil [Young] and then I did the Guitar Circus with [Peter] Frampton and Robert Randolph and invited them, so suddenly without really planning it, I had these incredible seven guest guitar players.

First of all, I’m standing on the shoulders of these two giant women in the rhythm section; that’s such a cement block. It’s amazing, and I get to stand on that and play rhythm guitar and sing. To have these [guest stars] come on top [of that] as kind of my beacon shining out to the world, sending out my signal, is just amazing.

It’s well-known that Kevin likes to track things live. Has that been a normal thing for you, as well?

It has. Way back to BTO days and even when I cut my own stuff, I try to do it live. Kevin was even more than that, because when you’re doing it live and you’re producing yourself, you’re kind of running back and forth. You do a track and you’ve got to put down your guitar and run back and listen to the playback. He’d just be sitting there and he’d stop us halfway through and say, “Wait a minute, that’s not fast enough.” And, “that’s not heavy enough. Let’s start over. You’ve got the energy; kick it up a few beats a minute.”

So, we counted in faster and we played it live, pretty much without a click track, just doing them. We’d give him two or three takes and he would say, “That’s it; we’re done. That song’s tired, you’re tired out, so move on.” We would move on and at the end of five days, we had these 12 tracks and he said, “I’ve got what I want.” He went back to Australia and did Jimmy Barnes and a couple of other bands, and then he went to Paris and did the new Iron Maiden album and he just got back before Christmas and said, “There are some solos that I’ve sent out to guys and they’ve sent them back. Here’s Neil’s solo and here’s Frampton’s.” I put it on and it was like opening Christmas presents. It was just amazing to hear that.

So, you hadn’t heard the completed songs?

No. We cut the 12 tracks in five days at Metalworks in Toronto. So, he flew in and I got the girls together and we just cut and cut and cut every day from like 10 in the morning until 10 at night. When it was all done, I said, “Can I have copies?” and he said, “No way.” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “I don’t want you playing these for anybody. I want to go home and listen to them and move a few things around, and I’m going to be back in September for four or five days. Come to Malibu and we’ll do some rough mixes. I’ll get Bonamassa to play and if you want to think of some other guitar players, we’ll send out some MP3s and see if we can get some other guys to play on them.”

So, it was done in five days, three days and then he got back on December 22nd and sent me all of these solos and I went, “Oh my God.” Frampton’s playing on “Heavy Blues” is amazing. He hasn’t played this way since Humble Pie's Rockin’ The Fillmore in 1970, you know? Because people think of Frampton doing his [imitates talkbox] – you know that crazy talking thing, which is cool – but he’s really an incredible guitar player. His playing on “Heavy Blues” is just amazing.

It really is. How did Kevin come into the picture originally and end up producing this album?

I met Kevin in the early ‘90s. I had done an album called Any Road and Q, the big classic rock network in Canada, every Friday night they did a new album live. So they asked me to come to Toronto and do five songs live from the album and talk about it. This was produced by Steve Warden who then went onto do that Elvis Costello Spectacle thing. He said, “You know, you can get your own engineer, or you can use the radio engineer. He’s a 22 year-old kid who is a whiz.” I figured, well, the 22 year-old kid is not going to know who I am or what I want or what kind of sound I like or what kind of heavy trucker bottom I like on my tracks.

My manager called me and said, “You know, I’ve got this engineer sitting in my house. He can’t leave the country. His name is Kevin Shirley. I want you to meet him, and maybe you could pay him a bit of money and he could mix your songs live on the radio. You’re only doing five songs. Give him a grand a song; he needs the money.” So, I go to meet him and I said, “What’s your problem?” He says, “I’m from Australia and I left my little boy at home with a child minder. I was flying to Toronto for one day to meet with Rush, because I was talking to Rush about doing their album.” [Shirley later engineered that album for Rush, which became 1994's Counterparts].

He said, “So I fly in in the morning, I meet with Ray Danniels and Rush, we make a deal to do their album and I go to fly home to New York and I can’t get on the plane. Something’s wrong with my work papers. So, my little boy is with a child minder who has to go home at 8 o’clock that night to her own family. I called her and said, ‘Please take my little boy home; I’m stuck in Toronto,’ and she said, ‘I can’t -- are you kidding me? I live in the ghetto.” This was a little blonde kid or something like that and [Kevin’s] saying “Please!” So anyway, long story short, he does my five songs and they’re great live on the air. I still have those mixes that he did. He got five grand, and he goes home and he pays her and he gives her all of the money and he’s a happy guy.

So when I sent him an email out of the blue like a year ago, I said, “Hey, do you remember me? I saved your ass in 1992.” He goes, “Yes, and I’ll save your ass now, but I’m booked for the next two years. I’ve got one week off now and one week off then and I’ll give you those weeks if you want them. But you’ve got to do me a favor. I don’t want any talkback. You must listen to me. If you want me to be captain of your ship, I’ll take your ship somewhere it hasn’t gone in a long time – and that’s maybe to the top or close to the top. But you’ve got to listen to me and trust me. That’s what Joe Bonamassa does and that’s what everybody who I work with, that’s what they do. Because everybody gets used to doing their own thing and I’m going to push you past where you would stop, and I’m going to pull you past your stop sign and get stuff out of you that you didn’t even know you could do anymore.”

And I said, “Okay, you’ve got it.” So he comes in and does it and gets these amazing vocals out of me – I never knew I could sing like that – in one or two takes. He got enough guitar out of me and then when I get a little bit redundant, in comes the guest soloists and it gets more exciting and it’s really cool.

Did you have a pretty specific idea as far as the direction you wanted to go with the songs or did that develop during the writing process?

To me, the three things that really shook me up and influenced my life and the rest of the world was the Elvis [Presley] wave and all of his clones of Rick Nelson and Gene Vincent and stuff, and then the Beatles and all of the other things like the Stones and everybody else from the early ‘60s. Then at the beginning of the late ‘60s, the power trios where Hendrix got to England, [Eric] Clapton had left the Yardbirds and started Cream and [Jimmy] Page was just starting Zeppelin and the Who was just going. These power trios brought more power into the blues and made the blues heavy, just like rock and roll, with pop music and rock and roll and suddenly it was heavy rock.

Suddenly this was heavy blues, and I don’t think anyone ever called it that, so I kept saying that, “I want to do heavy blues, like Cream and Hendrix and the Who,” like Wheels of Fire and stuff like that. Everybody would say, “Wow, that’s the psychedelic blues; nobody’s done that for so long. But, it’s big. It’s coming back in England and Germany and stuff, so I expect a lot of airplay over there. But now it’s kind of catching on here, and I’m getting emails and comments on Twitter and stuff saying, “Wow, real music again at last,” and these are guys that are 14 or 40 or guys from the ‘70s going, “Wow, something we can listen to and play to.”

The “heavy blues” part is an important thing to take note of. Sometimes you’ll hear that somebody is making a blues album, and you get it and it’s clear that they went for trying to recapture that textbook back porch blues sound – which often delivers varying results. With this album, it really feels like you went for something different.

Well, I had about half originals and half covers. I was trying to pay tribute to guys that influenced me and some people I haven’t even heard of, Bobby Blue Bland, Frankie Lee Sims, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Jimmy Reed. I’d be playing the song, and Kevin would come out and say, “What is that? Why are you doing that?” And I’m saying, “Well, it’s called, ‘Baby What You Want Me To Do’; it’s my favorite Jimmy Reed song.” And he said, “Well, last year, Jimmie Vaughan and Omar from the Howlers did a Jimmy Reed tribute album, and they did all of those songs. So why are you doing it again? It’s another yawn; you’re going to put people to sleep. Why don’t you speed it up and play it heavier?”

So I took that song and it became “Learn To Fly.” The first line is “Baby what you want me to do,” and I’m singing it just like Jimmy Reed, but it’s not the slow [version], it’s like powerful and louder and he’s going, “YES -- that’s heavy blues!” and I go, “Oh my God!” I go home that night and write the song “Heavy Blues” and then I play it for him and he goes, “Wow,” and I said, “Here’s what I’m trying to do: I’m trying to get the Stax/Motown sound, like 'Hold On, I’m Coming,’ you know, the horn section’s playing that song and I’m playing it with guitar, but I’m playing horn lines.” And he goes, “That’s great; repeat the line there and repeat the line there,” and then we sent the song to Frampton and he just knocks it cold. It’s fantastic.

How much of this stuff will you get a chance to play live?

I’ll probably play about half the album. If we’re getting airplay or feedback from a lot of the people, we will do that. I hate to go see an act myself – whether I know them intimately, like Neil Young, or somebody I’ve known for years – who says, “We’re going to take an hour now and play 22 songs from our new album that I wrote last week.” You don’t want to hear that. So, what I’m doing is, I’m combining them and I’m doing medleys. My show’s going to open with “The Edge,” which is the first song you hear when you put on my CD and that goes right into “Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet,” my No. 1 hit in 20-something countries with BTO -- back to back. It’s the same key and almost the same tempo.

Then I will do another hit and then I might put “Ton of Bricks” together with “American Woman.” You’re going to be getting a medley of something you really know. I’m going to start “American Woman” in the middle; we’ll sing one-third of “Ton of Bricks.” I’m not going to bore everybody with the whole song, and obviously there’s no way I can play Scott [Holiday]’s solo in that. It’s so incredible, it’s like Jimmy Page on speed. It’s amazing. I’ll combine a lot of the songs that way. That way I can sneak in four or five of my new songs and backsell it and say that, “That was from my new album Heavy Blues and Peter Frampton did the solo.” And then I go on and play my other stuff that people want to hear, “Takin’ Care Of Business” and things like that.

There seems to be a central character present in a lot of these songs, a guy who is a bit of a troublemaker and he’s done a lot of living.

Well, I’ve led a sheltered life and this was me kind of saying vicariously saying that, “Deep inside is a bad boy and the devil made me do it,” and that kind of stuff. Because everybody’s got a good and a bad side. My life has been so straight -- not that I’m going off the rails, but I wanted to get into this character. It’s like Steve Carell doing The Office, and then going and doing that latest movie where you don’t even recognize him. You want to do something out of character to show that you’re an artist, right? You’re really doing this.

So I got a chance to be somebody else in this, and my real life has radically changed in the last five or six years. I got the new band, I moved to a new place, I changed my domestic relationship, I got different guitars -- different things happened. I got a house in London, I got a house in Toronto and I just wanted to live the rest of my life in a different suit of clothes, in a different job with a chameleon kind of existence. In doing so, I’ve had a lot of self-discovery and I have a lot of friends who were not myself, but I would go with them to AA and NA meetings and hear these rituals that people have to go through to stay straight.

I’ve never done any drugs or drank or smoked in my lifetime, so I don’t know what that’s like. But to see them and their plight, that was really something. They all recite this mantra that yesterday’s history, tomorrow’s a mystery and all we’ve got is today. I am thinking, “What is my today?” A lot of it is living for today and a lot of it is exploring the bad side of life that I chose not to do, but I know all about it because all of my friends were doing it.

See Bachman-Turner Overdrive and Other Rockers in the Top 100 Albums of the '70s

The 10 Worst Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Snubs

More From Ultimate Classic Rock