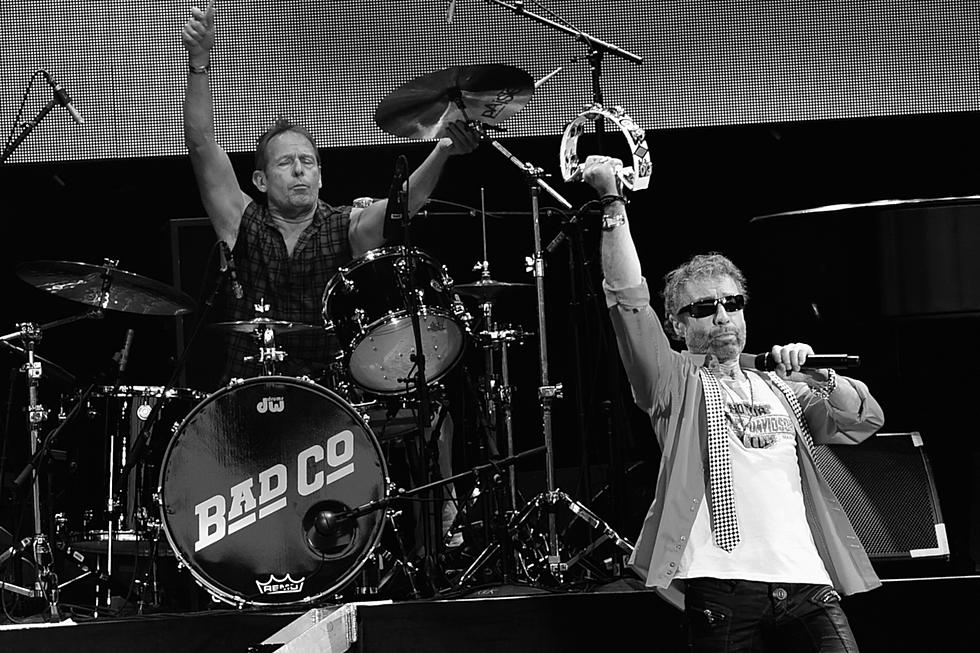

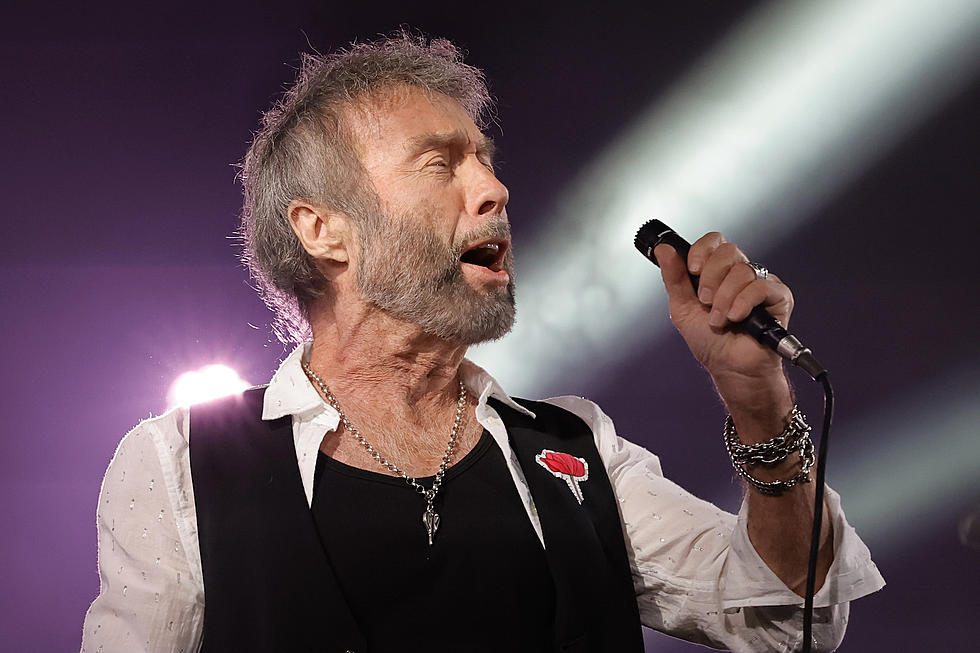

Paul Rodgers on Bad Company Tour: ‘It’s Good to Be Back Together’

It’s been 40 years since the formation of Bad Company. During our conversation with band's legendary singer Paul Rodgers, the veteran vocalist acknowledges that it’s been a “checkered career,” but it's also been one that has been filled with numerous highlights and success.

Bad Company will celebrate their milestone on the road this summer with Lynyrd Skynyrd, whose debut album celebrates its own 40-year anniversary in 2013. The two bands have shared the stage in the past, but this summer’s road trip will be the first time they’ve ever toured together, and it’s an experience that Rodgers is looking forward to.

Our discussion with Rodgers digs into the past and present, while also investigating the possibility of new music from Bad Company somewhere down the line.

It’s pretty incredible for Bad Company to be celebrating 40 years. There’s been a lot of things that have happened with you and the band in those four decades. What are your thoughts when you look back on that time?

It’s been a long 40 years, hasn’t it? But we all do other things too. It was 1973 when I started to put the band together at my country home in England with [guitarist and songwriter] Mick [Ralphs]. I got the idea for the song ‘Bad Company’ when I saw a poster for the Jeff Bridges movie, and it reminded of an old Victorian picture that I’d once seen and it said “beware of bad company.” So I sat down at the piano and started to write the song. I had a vision of the early settlers, the Civil War and the vast wide-open spaces and the lawless features of the Wild West, I think, when I wrote that.

I called Mick up, because we were thinking of names for the band, and I just said “Bad Company,” and there was this scuffling noise and he said, “Sh-t, I dropped the phone -- that’s it!” and we were off and running from there, really.

I mean, it’s been a checkered career. Because the early years, we started out when we were putting the band together in 1973. We went out [on tour] in 1974 and then we had a very strong run from then through the early ‘80s, and then I left to do other things. We’ve come back together over the years sporadically. We’re doing 25 shows, and I’m looking forward to it.

You mentioned the checkered history of the band. The inner workings of the group, like many groups -- it’s been a complex thing over the years with high points and then also disagreements. What is it that you enjoy about working under the Bad Company name? Because, clearly, you don’t have to.

My manager called me and he said, “You know, it’s 2013 and this is going to be the 40th year of the existence of Bad Company -- shall we do something?” The idea of touring together, I said, Yeah, it’s time. Because I think if you leave it long enough, we come back and we feel very fresh, and it’s good to be back together. So I’m looking forward to it. The last few tours that we’ve done, when we have come together over the period of time, have all been very, very strong and very exciting too. So I think that’s what I like about it. The chemistry is still there.

You’re heading out on the road with Lynyrd Skynyrd. How competitive were the two bands in the ‘70s heyday?

Oh, we loved each other, actually. I met them in the early days of Bad Company, and they all told me that they had been big fans of Free, the previous band I had been in, and they were hugely influenced by that. So we had great times, actually, and we always have. As a matter of fact, they introduced me to the lady that became my wife 15 years ago.

They would certainly hold a special place with you because of that.

Oh, definitely. And I was playing at the [Royal] Albert Hall once in London, and Gary [Rossington] flew all the way over just for a jam session towards the end of the set. We love those guys. It’s the first time that Bad Company and Lynyrd Skynyrd have toured together. I’ve toured with them as a solo artist, and we’ve done the odd sporadic gig together over the years, but this is the first time that we’ve done a series of dates together. Having said that, I have to say that the tour is 25 shows, some of which are with Lynyrd Skynyrd and some of which are just Bad Company by ourselves. What we’ll do is we’ll flip-flop as far as headlining goes. I think the two bands are very compatible musically, and the fans will get a good show.

Will there be some onstage collaboration between the two bands?

I keep an open mind. I did have a jam with the Lynyrds when they played up here at the Bluff. Hundreds of thousands of people turned out, and we had a jam there and it was good. I don’t know, though. I keep an open mind.

You guys launched your career with one heck of a debut album. You had already had a fair amount of success with Free prior to Bad Company. Did the debut Bad Company album feel like something special once it had been recorded?

Well, it was special. It was so organic. It was amazing because at the time, with the demise of Free, it was really sad, with Koss [Free guitarist Paul Kossoff] and everything that went down with that, so I wanted to put something together that was really together and very well organized. So musically, it was very organic. We wrote songs and we recorded them.

We were very fortunate that Peter Grant and Led Zeppelin were interested in getting behind the band and signing us. Because there were so many opportunities. They were so understanding of what it took to put together the kind of music that you really feel from the soul. They had this Headley Grange [mansion] with a mobile studio outside ready to roll, and they were going to make their album.

They were delayed, and Peter Grant said to me, “That studio time is available. You can go in there and use Ronnie Lane’s mobile and this old mansion to record whatever you can record.” We steamed in there and recorded everything that we had at that point -- in fact, we recorded that [whole] album. So it was organic in that sense, and it was very real. It was very rough around the edges but very real, and we were very gung ho to get it all down.

The great thing about being with Peter as a manager is that we didn’t have to worry about anything other than the music. "All you guys gotta to do is go in the studio and make your music." And it was great.

Peter Grant, aside from Bill Graham, seems like he was probably one of the most intense managers in the business, and you guys were lucky to have him in your corner. Do you have a good Peter Grant story?

Yeah, I have so many that I don’t know how many of them you want to hear. But someone else told me this about him. He was managing Gene Vincent. Do you remember Gene Vincent? [Rodgers sings a bar of ‘Be-Bop-A-Lula’] It was in the early days when people distributed vinyl records around the stores, and some guy had bootlegged about 100 copies [of one of Vincent’s albums] and he had them in his record store, and Peter Grant went around there. He went in there, and he said to the guy, “So, have you got any Gene Vincent records?” and the guy looks around shiftily and says, “Yeah, I’ve got one here.”

He shoves it forward, and he said, “Bring them all out.” The guy goes, "What?” And he said, “Get them all out on the counter now.” He puts them on the counter, and [Peter] goes pow! and he destroyed them. That was sort of typical of Peter['s] hands-on approach in those very early days. But at the same time, he was a very intelligent man. He wasn’t just a heavy. He was very intelligent, and he dealt with all of the top-flight lawyers and the brains of the business. So he had smarts too.

You said “hands-on,” and the stories I’ve heard, he wasn’t afraid to literally use the hands-on approach where needed.

Well, he was a very big guy and an ex-wrestler. But you know, we never feared him. We didn’t walk in terror of him. He was like a gentle giant as far as we were concerned. It’s just that he was very passionate about looking after his boys, I think that was really all it was.

From a collaboration standpoint, did songwriting with Bad Company feel different than what you had done prior to that? And did you feel like you had progressed as a writer at that time when you formed the band, or would that come later?

You’re constantly looking for ideas. When I first started writing songs, I looked around at the bands that were making it, and they all had the original material. Jimi Hendrix, the Beatles, the Stones -- everybody was writing their own songs. That’s the way that you established your own identity.

Free, at that time, we were a blues band with a couple of songs that I had written: ‘Walk In My Shadow,’ and I wrote one with Koss called ‘Moonshine.’ We weren’t seriously writing songs. But it suddenly occurred to me that if we could write enough songs that we could do a whole set of our own material, we would be very, very unique. We would be a force to be reckoned with.

I explained that to the guys, and we went for that. Eventually, we did have a full set of our own material, and it all came out of the blues in many ways. So once I’d become a songwriter, it just stays with you. You always want to write more songs, because it’s such a great feeling. I find that sometimes I can collaborate with a person. I did a lot of that with [Andy] Fraser in the first band, and then sometimes I write by myself. Currently, I’m collaborating with a guy in New York called Perry Margouleff. We’re writing away furiously and recording stuff, and we’re doing it all in analog. So I’m really excited about that. It’s an ongoing thing.

As a songwriter, did you find yourself at a crossroads going into Bad Company? Because it seems like Free ended before you thought it would.

No, I don’t think so. There’s always ongoing material [being created]. But having said that, when we were putting the Law together, me and Kenney Jones, I said, You know what? I’m not going to write songs for this. Let’s just get people to write songs and bring them in. And I did find it very difficult to find really great songs, and in the end I thought, Wow, you’re better off, if you want material, writing it yourself.

That album from the Law was coming around in a period where artists like yourself were being encouraged by the record labels to use outside writers.

Yeah, and there was a lot of record company influence in that, and I don’t think that’s a good thing. I think they’re great for what they do, but their strength really is marketing. The strength of a band is to make the music. I’ve come full circle with this because Perry, my current songwriting accomplice, we talk a lot about how it was in the old days and how we can recreate that in terms of the natural nature of putting things together, [where] you’re not concerned too much about perfect tuning and perfect arrangements, perfect this or perfect that.

Because I find that if you’re in the studio, there’s so much that you can do to perfect a thing that you can lose the spirit in the process. A lot of those old soul and blues records were great because they were so spontaneous. And they might have been recorded in some hotel room with a microphone stuck in front of them, and the quality might not be great, but the spirit of the thing, it just comes down through the years, and you can listen to it through all [types] of technology and [still] be moved by it. You think, Wow, there’s something there that we’ve got to recapture. And that’s the spirit of the power of music.

The new songs that you’re working on, where are those going to wind up?

I don’t know yet. There’s a couple of things I’m doing. I went down to Memphis, and I recorded in the Royal Studio down there with Al Green’s band, and we just nailed tracks down. And again, it was very natural and organic, just the way it was [back then, with] a couple of takes until we got it straight and then we went for one. I loved doing it. That’s going to come out this year -- we’re mixing that now.

Perry and I have been working on the new [material] for a number of years now with no real actual focus as to when it’s going to come out. But I think we’re close now, so it will be probably early next year.

We [already] had one [song] out called ‘With Our Love,' and we put that out as a download to help some horse sanctuaries that we were behind at that time. We did manage to save quite a few horses with the proceeds of that record. So that is out there as a download.

The album that is coming out this year, is that originals or covers?

It’s [covers of] my soul influences [like] Otis Redding. A lot of Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, Ann Peebles is in there -- a lot of people that influenced me. It’s music that I love, and it’s from the heart, really. And the band is just so awesome that it’s great. They do these things where we’ll build the song up, and all of the sudden they cut down, and it’s time to testify! They do that, and it’s just amazing. They’re actually going up to the White House to play for the President.

With Bad Company, is there a possibility of doing a new album?

I keep an open mind. It depends how everybody is when we get together. We’ve got a lot of songs. I was putting the set together and there’s so many songs, and I’m thinking, Well, that about covers it. And then I think, Oh geez, I haven’t got ‘Ready for Love’ in here. And that’s a major song. So there’s a lot of material to play. But having said that, it’s always nice to have fresh songs, and I have no doubt that Mick’s been writing, and I’ve [also] been writing. So we’ll see how we are when we get together.

There were the four songs that came out with the anthology in ‘99. I was just curious if you had written any songs with Mick since that time.

Not as such, no. Writing, yes, but not together.

How difficult was it to be the guy out in front of Queen who wasn’t Freddie Mercury?

It was a challenge. Where we got into that was that we did a TV show where I was asked to close the show. It was for Island Records, and Chris Blackwell asked me to close the show with ‘All Right Now.’ Queen were also on the bill, and Brian [May] said to me, “Look, we’d really like to play live on this show. How about we’ll be your backing band for ‘All Right Now’ if you’ll be our singer for ‘We Will Rock You’ and ‘We Are the Champions'?" So I said, OK, that sounds like fun. We did that, and it was such a great thing that we all came off ecstatic after we played. It was one of those situations where you do a jam and everyone says, Yeah, we’ve got to do this again. And everybody goes away and gets busy, and nothing really happens. But this time it did.

Brian and Roger [Taylor] called me and said, "Look, how about doing a few gigs just for fun as Queen + Paul Rodgers, and we’ll do 50 percent of your material and 50 percent of ours? I thought about it for a bit, and I said, I’ll tell you what, I would like to do this, but because Queen has not been on the road for such a long time, we’ll make it Queen-heavy. So we did about a quarter of my material, and they did it great. It was a trip, I’ll tell you. The fans [enjoyed it].

We went into the most obscure parts of Europe that I’d never even heard of, and we’d had the king of Lithuania, I swear to God, come and play drums for us -- on ‘All Right Now,’ actually. We visited the palace, and he said, “Oh, I play drums, you know?” And then he comes and plays drums with us. So those kind of things happened, and it was quite amazing, actually. I really dug it, and we’re still good friends. But, you know, it’s funny, it absorbed so much of my time. It was four years that I was with those guys, and it flew by, and I was like, Wow, am I really going to spend the rest of my career doing this? And I thought, No, I don’t think so -- I’ve got to move on back to my own stuff. But we would maybe do something if there was a charity event.

It just seems like that would be a challenging thing for you as an artist. Was there anything more challenging than that or a situation like when you started a new band with Jimmy Page and the Firm? Those are two examples that I think of that had to be daunting for you as an artist.

Yeah, I think so. But I only do things though that feel right at the time. If it doesn’t feel right, if it’s simply just scary, there’s not a lot of point in doing it. You have to really believe that this is a good thing and you can do it. I just got back from Germany -- I did 20 shows out there with a 50-piece orchestra. I thought that was going to be quite easy, but, in fact, that was very daunting, because it’s very exacting. And I loved the orchestra, [which featured] young kids from Czechoslovakia and a choir and everything.

I had to curb myself because I’m so used to that thing with the band where we jam. The guitar solo could go on a bit longer and it’s fine, or I’ll throw in another chorus. But you can’t do that with a 50-piece orchestra. You’ve got everything written out, and you put everything out of sync if you do that. There were a couple of times I threw an extra chorus in there and I’d look around and see a horrified conductor, and I’d go, Oh, I’m sorry! But bless them, they did adjust, and we kind of adjusted to each other. That was an amazing experience.

With Bad Company, did you tend to write and record more material than what made the final records? How much stuff is in the vaults? Because Bad Company is one of the few bands that haven’t really done expanded-album reissues.

I honestly have really deep reservations about releasing everything you ever did. Every time somebody farted in the studio, now it’s out there. I look at it this way: Suppose you want to write a love letter, and you write, "Dear so-and-so: I love you, blah blah blah,” and you throw it away and then you try again. After like five or six attempts, you have your love letter that you want to send, right? It’s like having somebody come after you and pick up all of those pieces that you’ve crumpled up and thrown in the bin and put them out on the Internet, right? That’s what it’s like for me.

I think it’s of passing interest maybe to [learn] “How did they evolve this song?” But I’m not really all that keen on it. Island Records are going to be doing that with Free, and they’ve just opened the vaults, and I just feel it’s a bit embarrassing, to be honest. So I don’t think we’ll be doing that. If there is anything, I think we’ve culled really the best of Bad Company from the masters that we’ve put out. The best way forward is actually forward, I think, and that would be to record new stuff.

More From Ultimate Classic Rock