20 Years Ago: ‘Detroit Rock City’ Movie Pretty Much Ends Kiss Reunion

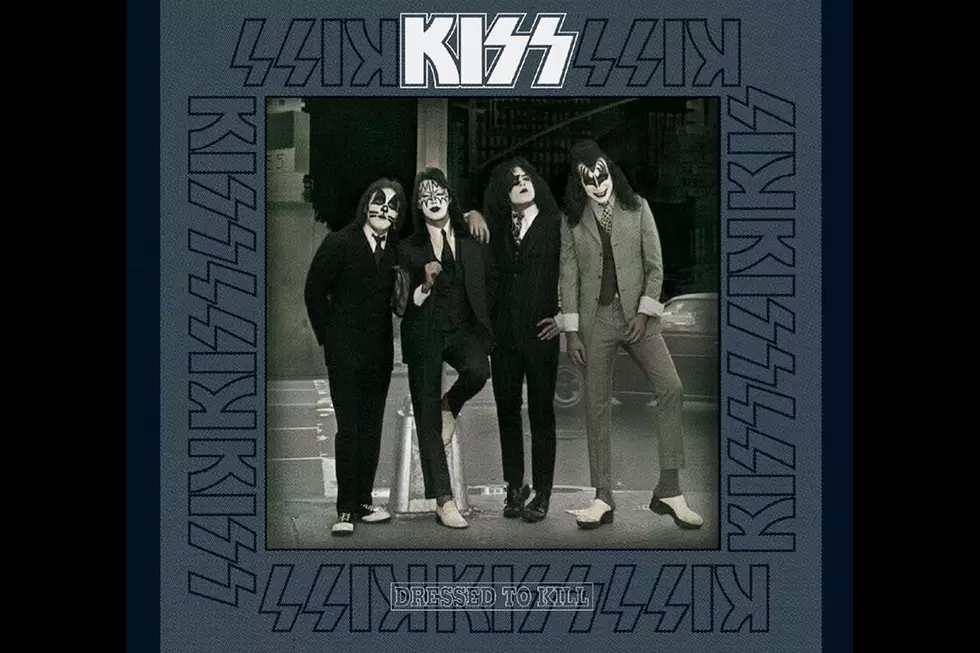

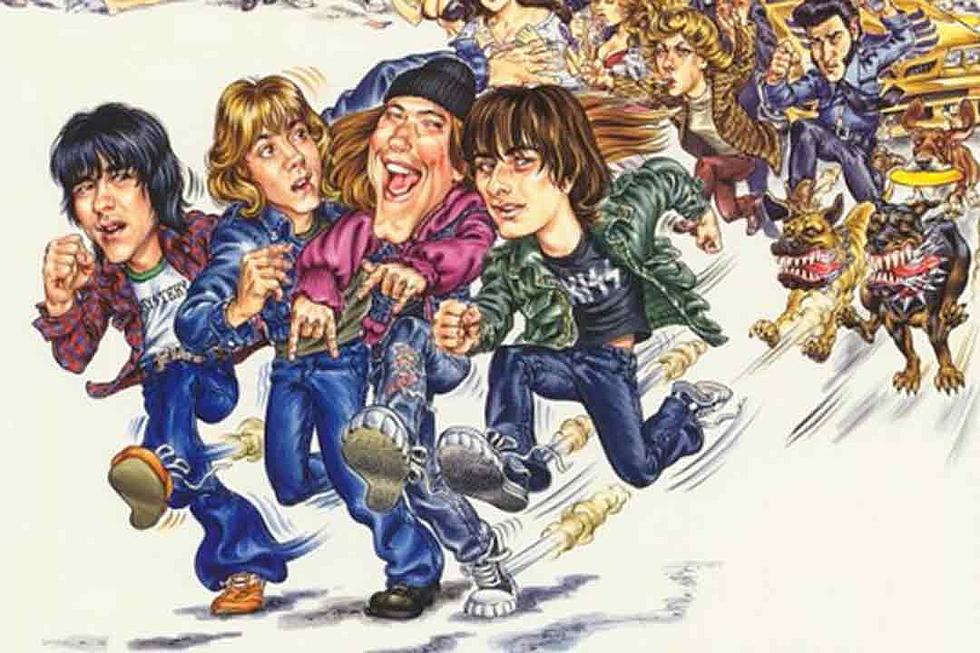

For many film fans who don't happen to be card-carrying members of the Kiss Army, the 1999 movie Detroit Rock City is little more than a cinematic footnote -- an unsuccessful rock comedy that used a Kiss concert as the grist for a '70s-set storyline that attempted to hearken back to cult classics like Rock 'n' Roll High School. But for former Kiss members Peter Criss and Ace Frehley, the events leading up to the movie's Aug. 13, 1999, release helped bring their time with the band to a permanent end.

According to Criss, the movie started as a passion project for producer Tim Sullivan, who'd befriended Gene Simmons after interviewing him for Fangoria in 1983. Given the embarrassment the band had suffered with the infamous Phantom of the Park project in 1978, Simmons knew the script for any Kiss film needed to be just right -- and they found it in a screenplay from writer Carl V. Dupre, whose previous credits included eight episodes of the TV series Bone Chillers.

The story -- about a group of four Kiss-loving Cleveland kids (played by Edward Furlong, Giuseppe Andrews, James DeBello and Sam Huntington) who must endure all sorts of shenanigans in order to make it to a show in Detroit -- seemed to play directly to the band's image while leaving plenty of room for the kind of good old-fashioned teen high jinks that crowded the drive-in during Kiss' late-'70s heyday. But according to Criss, things started to go wrong almost immediately, and it was all Simmons' fault.

Watch 'Detroit Rock City' Trailer

"Ace, Paul [Stanley], and I didn't even know about the movie until we read about it in the Hollywood Reporter," Criss recalled in his autobiography, Makeup to Breakup: My Life in and Out of Kiss. "After we met with Tim and the producers, I was excited. This wasn't some Hanna-Barbera pablum, this was a real movie with a director – Adam Rifkin, whom I had heard about and admired for his movie Mousehunt. I really wanted work on it, but then Gene started f---ing everything up."

From Criss' point of view, Simmons' heavy-handed approach extended to every level of the production. When it came time to plot out the soundtrack, Criss alleged that in order to grab a bigger piece of the profits, Simmons refused to include any songs that weren't written by himself and Stanley -- a big deal for Criss, because it meant eliminating his signature number "Beth" -- and proceeded to micromanage the script in ways that embarrassed Criss and Frehley.

"He had them take out a scene where the kids meet us backstage because, according to him, 'Ace and Peter can't act,'" reads another passage from Makeup to Breakup. "Then he told the other producers and the director that Ace and I were like children and we needed to be kept on a tight leash."

It was all part of what Criss said was Simmons' aspirations to branch out into the film and television industry. Accusing Simmons of "licking every New Line a--hole he could find" because "he was so desperate to break into Hollywood," he added, "I remember we'd all be in a limo and Gene would say, 'Can we have some quiet in the car, please? I'm expecting a call from Steven Spielberg.' Of course, the call never came."

Whether or not any of that actually happened, there's other evidence to suggest that Simmons may have been somewhat distracted by Detroit Rock City. Sullivan recalled Simmons calling him on his cell phone to discuss the movie while Criss was in the middle of his drum solo during a Kiss gig. And unfortunately, not even the opportunity to revisit one of their classic cuts for the soundtrack could heal the divide.

According to Criss, producers asked Kiss for a new version of the song "Detroit Rock City," and although it took a little prodding to get things going, they ended up convening in the studio to cut the track -- which Criss says was the last the original lineup ever recorded together. Sadly, due to what Criss describes as a mix-up, it didn't even make it onto the soundtrack.

It wasn't the only unfortunate last-minute edit, either. According to Frehley, his daughter Monique filmed a scene in the movie at Simmons' suggestion, only to discover at a private screening that her appearance had been left on the cutting-room floor.

"I knew it wasn't an accident," Frehley insisted in his book No Regrets. "Gene had been involved in the editing process on a daily basis. I even remember getting tapes from him, early on, with alternate scenes and endings, but Monique's scene was always included. I knew Gene was probably pissed at me for something I had done, but to get back at me by hurting my daughter? I mean, it was his idea in the first place, so what the f--- was he doing?"

If Simmons was truly behind the edit, he had Rifkin's support. "Gene was a fantastic producer to work for. He loves movies and is very respectful of the process. Whenever we found ourselves at a creative crossroads with each other he would always defer to me because I was the director," Rifkin enthused in a later interview. "He also fought on my behalf against the studio if there ever was a creative disagreement. Gene’s great."

Regardless of who was ultimately responsible, Frehley found it impossible to forgive Simmons for hurting his daughter. "I never felt the same about Gene after that. He had reached an all-time low with me, and this particular snub contributed greatly to my second departure from Kiss."

Ultimately, all that angst didn't add up to much in the way of ticket sales. Detroit Rock City pulled in less than $5 million during its theatrical run, a disastrous showing for a movie with a reported $34 million budget. It eventually acquired something of a cult status on the home-video market, but the damage was already done as far as band relations were concerned.

Even worse, according to Criss, was the way Tim Sullivan was bumped out of the spotlight after Detroit Rock City got the green light at New Line -- then laughed at when he allegedly confronted Simmons about using the movie to belittle Criss and Frehley. "We dyed our hair, we gave our blood, we struggled and cooked for each other in seedy hotels because we were a band, not a brand," Criss lamented. "It's shocking and horrifying that Gene has forgotten that."

The Best Rock Movie From Every Year: 1955-2018

More From Ultimate Classic Rock